Facebook, Google, and Twitter have faced hard questions about the data they collect on their users and what they do with that information. Often lost in this justifiable alarm over online privacy, however, is a platform that knows a staggering amount about its customers’ home lives, spending habits, and even physical health: Amazon.

Amazon’s vast offerings—which include online as well as brick-and-mortar stores, an internet pharmacy, streaming services, smart speakers, security cameras, mobile apps, and a digital advertising network—have helped the company expand into nearly every aspect of people’s lives. The ongoing coronavirus pandemic, meanwhile, has increased Amazon’s data collection opportunities, with more consumers shopping online as well as working and schooling at home, which allows Amazon’s smart speakers to eavesdrop on quarantined users.

All of these interactions amount to a mind-boggling amount of user data for Amazon, and raise questions about the company’s plans for this personal, often highly sensitive, information. With Amazon gobbling up more and more insights about consumers and their behavior, the Tech Transparency Project (TTP) conducted a review of the company’s privacy policies, patent applications, and other open-source information to assess the full scope of its surveillance capabilities. The findings show that Amazon is collecting far more data about its users than many people realize.

In addition to purchases on its platform, Amazon may collect:

- Profiles of users’ routines and habits

- Detailed user location data

- Purchase history at brick-and-mortar retailers

- Images and recordings of visitors to users’ homes—including children

- “Voice fingerprints” of everyone recorded by Alexa-enabled smart home devices

- Recordings of calls and conversations placed through Alexa

- "Keyword information” about likes and dislikes derived from user conversations

- Browsing history on third-party websites that show ads through Amazon

- Information about how users interact with a webpage, including what they linger on

Amazon can use this information to draw inferences about people’s demographic information, interests, financial health, and even their moods and romantic preferences. One Amazon patent application describes what appears to be a dating service that matches users based on their online browsing and purchase history. Other Amazon technologies use voice and video to determine user emotions.

Amazon’s on-platform advertising and its rapidly growing ad network allow the company to monetize this data, putting it on course to catch up to the tech industry’s advertising giants, Google and Facebook. At the same time, the company has found other ways to monetize its user information, extending credit and insurance to users based on their Amazon data alone.

The picture that emerges from TTP’s review is a company with a voracious appetite for information about consumers, operating with little scrutiny and few checks on its ever-expanding grab for personal data.

Browsing and Buying at Amazon

Amazon’s online marketplace is responsible for nearly 40% of online retail and 4.6% of all retail sales in the United States. The company’s 2017 acquisition of Whole Foods put Amazon on track to become one of the top five grocery retailers in the country. As of 2019, nearly 100 million Americans used Amazon’s streaming service, Prime Video. These services together produce an astonishing amount of data about American consumers.

Purchase History

Among tech firms, Amazon is unique in that it owns data not only on what consumers might want to buy, but also what they actually do buy, down to the size and color of the product. Amazon maintains the complete purchase history for every customer, and uses this information to make inferences about the customer’s interests, habits, and potential future purchases. Amazon allows users to “archive” past orders so that they will not show in the default purchase history view, but it does not provide a way to delete this information from its system.

This purchase history may include Kindle downloads, streaming videos viewed through Amazon Prime, audiobooks downloaded from Amazon’s subsidiary, Audible, and music streamed via Amazon Music. An Amazon patent from 2017 describes analyzing media consumption data to determine the “intensity of interest” in a particular artist, and using that information to set an individualized price for tickets to that artist’s events.

With the recent launch of its online pharmacy to sell low-cost prescription drugs, Amazon purchase histories will soon contain even more intimate information about users’ health and well-being.

Zappos is one of many Amazon subsidiaries that share purchase data with their corporate parent.

Amazon’s purchase history data can also include purchases at Amazon’s subsidiaries. Online retailers like Shopbop, 6pm.com, and Zappos share purchase data from their sites with Amazon, their corporate parent. This data includes personal information, like emails and phone numbers, that Amazon can use to associate purchase histories from different websites with the same individual. The company also captures spending beyond its network through its co-branded credit cards and Amazon Pay, a platform that allows customers to process transactions on third-party retail sites through Amazon.

Amazon has also devised a way to track purchases in brick-and-mortar stores. In the retailer’s bookstores, customers cannot pay with cash—they must use their Amazon account or a credit card. At the company’s cashierless Amazon Go convenience stores, an app tied to the user’s Amazon account had initially been the only way to pay. Amid a backlash, the company said in 2019 that it would accept cash at some stores, but the stores remain “optimized for payment cards.” At Whole Foods, Amazon Prime members get discounts by providing the phone number associated with their Amazon account or scanning a bar code on an app that is signed in to their Amazon account.

Amazon uses its vast trove of purchase history data to draw conclusions about its users. The company recently replaced much of its retail workforce with artificial intelligence that uses customer spending data to algorithmically predict future demand for products. A 2019 patent application describes a method of analyzing past purchases to predict future behavior.

Amazon has also imagined more startling applications of its purchase history data. One company patent describes a dating-like service that matches users based on their purchase histories, web browsing data, and search histories. Another patent describes determining “age, gender, preferred languages, and the like” from the user’s purchase history as an alternative to the customer providing that data.

Web Browsing Data

Amazon tracks the products that its users contemplate in addition to the products that they actually buy. The company and its subsidiaries maintain records of every product the customer searched for and viewed on their websites. Cookies allow the company to track users’ browsing activity even when they are not signed in to their Amazon accounts.

According to market research website SimilarTech, nearly 490,000 websites are a part of Amazon’s third-party ad display network, Amazon Publisher Services. Websites that use Amazon Publisher Services may contain a tracking cookie that allows Amazon to see who viewed ads served through their network. Amazon attempts to associate this information with users’ accounts, thereby combining browsing data with other personally identifying information. Tens of thousands of websites also track users through the Amazon Associates Program, which allows influencers to make money by including links to Amazon products on their websites.

Amazon collects user data through its own app as well as its mobile ad network.

Amazon’s trove of user browsing data also includes activity on mobile apps. The Amazon Mobile Ad Network allows Android and iOS developers to serve Amazon display ads in their apps. Apps that serve Amazon ads send the user’s unique device identifier, or Advertising ID, to Amazon. Amazon also has its own app, which collects browsing data just as the company does on its website.

In determining user interests, Amazon draws upon browsing and purchase history on its own site in addition to browsing activity on third-party sites. In 2015, Amazon filed a patent for selecting advertisements based on users’ browsing and purchase histories. The patent notes that in addition to sites visited and items purchased:

Various other information may be aggregated about a customer in the customer data through the browse history and order history such as, for example, addresses, spending history, estimated income, estimated age, family demographics, hobbies, interests, pets, other demographic data, and so on.

Another Amazon patent describes tracking where users scroll on a page, how long they linger on an item, and how they move their mouse to determine user interests.

Financial Data

Amazon’s comprehensive transaction histories for every customer may be one of the largest repositories of personally identifiable spending data in the world. This data tells the company so much about its users’ financial lives that it does not require traditional documentation to provide financial services to its customers.

Amazon’s privacy policy states that the company uses information from credit bureaus to offer financial products to some customers, but it offers many financial products without drawing on outside data at all. For example, Amazon offers customers the option of paying for a product in monthly installments on the basis of “your transaction history and past products purchased on Amazon.com,” but the company explicitly states that it “will not use a credit report to determine your eligibility.”

The company also mines third-party sellers’ accounts for financial information. As of 2017, Amazon financed $3 billion worth of small business loans based solely on the data that it has gathered through merchants’ interactions with its platform:

Unlike traditional lenders that may have lengthy loan applications that require all types of documents, Amazon uses internal algorithms to invite sellers to the program based on the popularity of their products, inventory cycles and other factors.

In 2020, Amazon announced a new credit offering in partnership with Goldman Sachs. As part of the deal, Goldman will use data on Amazon Sellers collected from the ecommerce platform to determine eligibility for credit.

According to Amazon, the company’s losses on its loans have been “very, very small.” By analyzing what people buy and sell, Amazon may know more about its customers’ financial health than traditional banks do. The company also draws upon its consumer data to offer insurance to select customers in India and Europe.

Recent reports indicate that Amazon may soon offer a broader array of financial products. This year, Amazon launched its first auto insurance policy in India. The company boasts that the application process takes less than two minutes and requires no paperwork.

Echo, Ring, and the “Internet of Things”

Amazon’s vast store of user data doesn’t end with what users browse, watch, and buy. The company is also listening—and watching—through its line of Echo smart speakers, Ring home security cameras, and wearable tech. Roughly 42 million American adults have Amazon smart speakers in their homes, and hundreds of thousands more use the company’s Ring security cameras.

Alexa Interactions

Amazon’s smart speaker, the Echo, greatly expanded the company’s access to information about users’ lives. Through voice commands spoken to its Alexa operating system, Echo users can search the internet, order products from Amazon and other retailers, contact local businesses, order a ride share, listen to audio, check their calendars, control their smart home devices, call or text their friends, and play games. Amazon retains a record of every request users make of Alexa:

Amazon processes and retains your Alexa Interactions, such as your voice inputs, music playlists, and your Alexa to-do and shopping lists, in the cloud to provide, personalize, and improve our services.

Amazon's Echo smart speaker gives it a wealth of new insights into user behavior.

Even when a user is not interacting with their Alexa-enabled smart speaker, the speaker remains in a so-called "passive listening" state in which it records short snippets of audio and checks to see if they contain a "wake word," like "Alexa," that initiates an interaction. Once it hears a wake word, the Echo transitions from a passive listening state to a “responsive state” in which it records user interactions and sends data to Amazon’s servers. In order to determine when the wake word has been spoken, the Echo constantly captures and analyzes audio.

Amazon says it only retains records of what users say following the Echo’s wake word. But news reports have documented multiple instances of the Echo spontaneously transitioning into its responsive state without users saying the device wake word. Even when the Echo is triggered accidentally, the device records audio and transmits it to Amazon’s servers. On at least two occasions, an Echo also sent audio that had been inadvertently recorded to one of the device owner’s contacts.

Amazon employees are also listening in. Thousands of Amazon employees and contractors review Alexa interactions in order to train the company’s artificial intelligence, offering the workers an intimate look into Echo users’ homes. Sometimes, these workers hear audio that the user does not intend to transmit to Amazon:

Occasionally the listeners pick up things Echo owners likely would rather stay private: a woman singing badly off key in the shower, say, or a child screaming for help… Sometimes they hear recordings they find upsetting, or possibly criminal. Two of the workers said they picked up what they believe was a sexual assault.

Amazon allows users to delete the voice recordings their smart speakers have transmitted to its servers. But as CNET reported in May 2019, this may give consumers a false sense of privacy, because text logs of the interaction remain on Amazon’s servers even after a user deletes the audio.

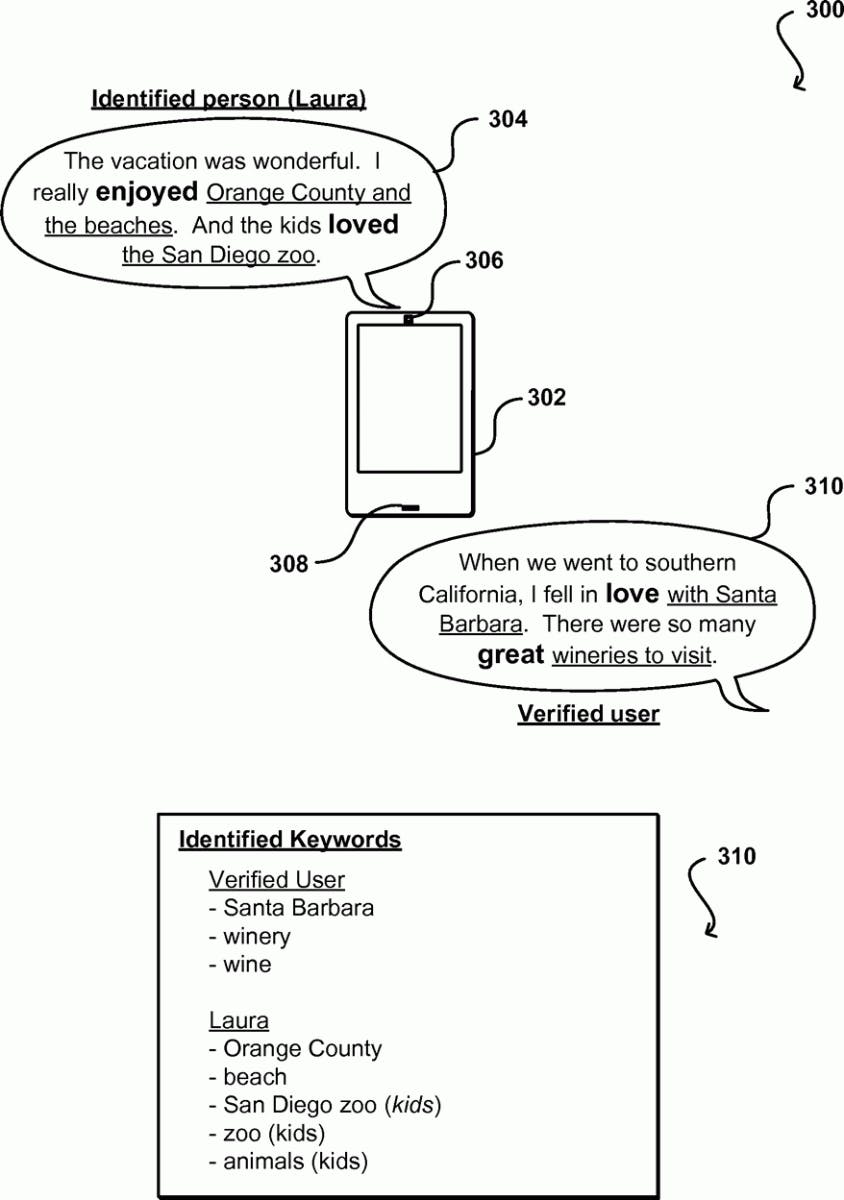

Illustration from Patent Application 14/447487, “Keyword Determinations from Voice Data”

Amazon considers voice messages placed over its Alexa Calling service to be Alexa interactions, which the company records and saves. A 2014 patent application shows how Amazon might mine conversations that take place over Alexa Calling for advertising keywords. The patent describes an algorithm that listens for sentiment words such as “like,” “dislike,” or “enjoy,” captures the audio adjacent to those words, and extracts keywords associated with a positive or negative sentiment. The patented technology could assign keywords to specific individuals via a “voice fingerprint,” and serve targeted ads to users based on this information.

The technology would analyze speech for interest-based keywords locally on the Echo, and transmit that data back to Amazon in text form. Because the technology described in the patent does not send any audio to Amazon servers, this practice does not technically contradict Amazon’s privacy policy or its promises to its customers that it only retains audio data from interactions with the Echo in its responsive state.

Amazon focuses a great deal of attention on associating Alexa interactions with specific individuals. In 2017, Amazon introduced Alexa Voice Profiles, which allows users to train Alexa to associate different voices with specific individuals. Amazon links users’ voice profiles to their Amazon accounts in order to “personalize your experience.”

A careful reading of Amazon’s Alexa documentation reveals that Alexa also uses voice fingerprints to identify individuals even if the user does not set up a voice profile:

Alexa can automatically recognize the voices of users in your household over time to improve personalization of certain Alexa features. … When Alexa recognizes your voice automatically, or when you create a voice profile, Alexa uses recordings of your voice to create an acoustic model of your voice characteristics. Alexa stores these acoustic models in the cloud.

This technology allows Amazon to identify, profile, and potentially advertise to users even if they do not have an Amazon account associated with the Echo. That means that visitors to an Echo user’s home—including kids—might get scooped up in the company’s data dragnet. In a complaint filed at the FTC in May 2019, consumer advocates raised the Echo Dot Kids Edition’s “playdate problem,” noting that Amazon does not give notice, or obtain parental consent, before recording children who are visiting a home that contains a device.

Voice fingerprints can tell Amazon more than just who’s home and what they like. The company is also using voice data to determine users’ emotions. The MIT Technology Review reported in 2016 that Amazon was working on determining emotion from users’ voices. The technology appears to be incorporated into Amazon’s new wearable fitness tracker, which told New York Times tech columnist Kara Swisher that she sounded “restrained and sad” during a recent test of the device.

Video and Images

Amazon is also interested in how its users look. The camera-equipped Amazon Echo Look, which was discontinued earlier this year, sent users’ photos and videos to the cloud, and encouraged users to share photos with Amazon “fashion specialists” for a “style check.” While the Look’s machine learning algorithms were allegedly focused on analyzing the user’s outfits, they could also be trained on anything in the picture.

Amazon could also solicit users’ body measurements in order to provide recommendations about how clothes fit, as described in a recent patent. The company’s new wearable health monitor, Amazon Halo, prompts users to upload images of themselves in form-fitting clothing so that its software can provide a “body tone” analysis. The company recently launched another service called "Made for You" that solicits images of customers in form-fitting clothes to produce custom-fitted T-shirts.

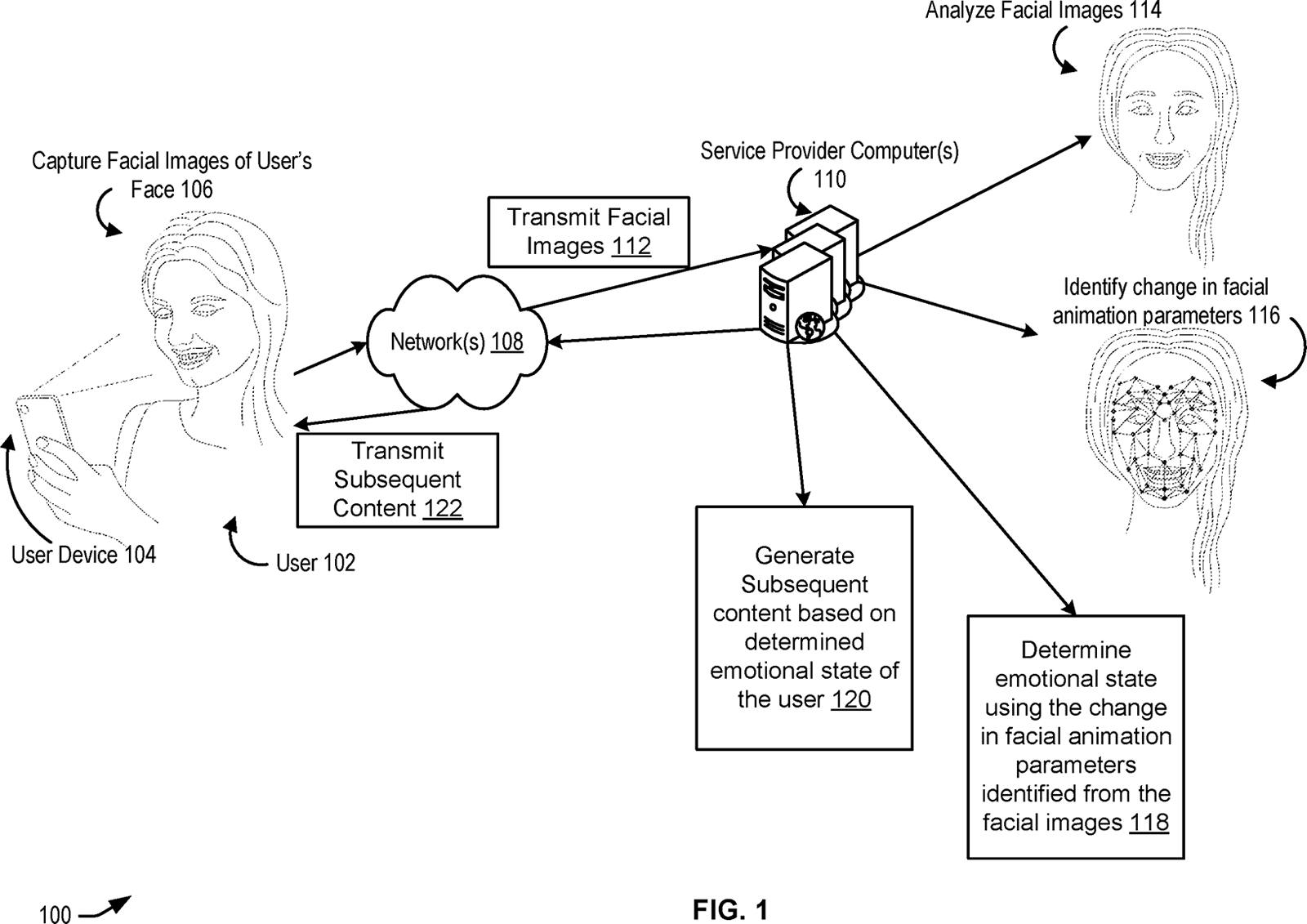

Not content to rely on voice alone to determine how users feel, Amazon has also filed patent applications to use head position and facial expressions to interpret users’ emotions. One of these patents describes using facial expressions to determine the “emotional impact or response” of advertisements shown to the user.

Amazon is also collecting video data of users’ homes and surroundings. In 2018, the company acquired Ring, whose video doorbells share data with hundreds of police departments. Amazon admitted in 2019 that it did not place any restrictions on what law enforcement does with the videos they obtain through Ring. The company also makes some Ring camera footage available to the public through its Neighbors app and marketing materials. Some of this footage depicts minors whose parents may not have provided consent for their children to be recorded.

This year, Amazon announced that it would soon begin marketing the Ring Always Home Cam, an autonomous surveillance drone designed to patrol the inside of users’ homes by video. Critics were quick to point out that the technology could easily be coopted as a tool of domestic abuse. For its part, Ring seems to think that allowing family members to surveil each other is a selling point: In 2019, the company put out a press release to promote an episode in which a 19-year-old woman’s father used the family’s Ring doorbell to interrogate her date.

Location Data

Amazon gathers data about users’ locations even beyond the places where people receive their Amazon packages. Amazon’s websites and apps transmit the user’s location to the company. When app developers use Amazon’s advertising technology, they may also collect precise location data (with consent) and send it to Amazon. The introduction of wearables to the company’s product line will no doubt expand the company’s repository of location data.

Recent reports have raised additional privacy concerns. An Amazon team tasked with reviewing Alexa users’ commands to help improve the voice assistant’s performance had access to location data, according to Bloomberg. The employees said they could easily use the geographic data to find users’ homes.

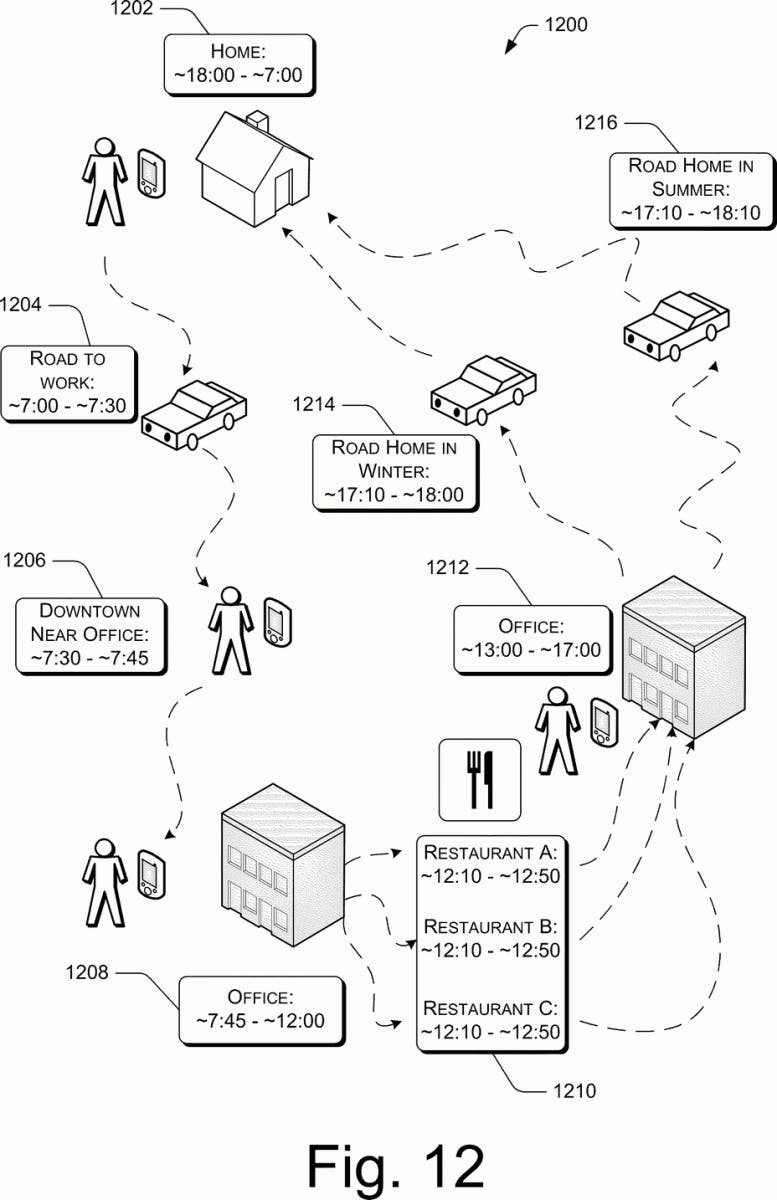

An Amazon patent for a technology that automatically processes payments when a user’s phone is detected at a retail location—a key technology for the company’s cashierless Amazon Go convenience stores—describes a security mechanism that would map a user’s every move in order to identify anomalous movements that might suggest theft. According to the patent, this technology would allow the company to create a “geolocation signature” of time-location data points to determine a user’s routine. The patent also discusses using this information for advertising purposes.

Another patent, for predictive travel notifications, describes profiling users’ movements in detail:

The travel patterns include a user's geographic movement habits, such as where a user travels at particular times of day or days of the week, favorite routes a user typically takes to a destination even when a favorite route may not necessarily be the fastest route to the destination, and the like. Instead of keeping the collected travel data anonymous, as with certain conventional traffic monitoring systems, the travel data can be associated or linked to the user's account or stored in a user profile in order to build a set of travel patterns for the user over time.

Illustration from Patent Application 15/438633, “Transaction Completion Based on Geolocation Arrival”

By storing detailed location histories in user profiles, Amazon can gain deep insight into users’ lives even when they are not interacting with Alexa or browsing the web.

Conclusion

Amazon continues to burrow deeper into its customers’ lives, adding products and services to cover nearly every human need. At the same time, Amazon Prime memberships keep users in the company’s ecosystem by incentivizing them to get their money’s worth from the program’s hefty annual membership fee. These tools give the company extremely precise insights into the commercial, domestic, travel, social, physical, financial, and even emotional lives of its users—and their friends and family. Amazon then sells that information to advertisers in the form of highly targeted ad placements.

Amazon’s data-collecting machine has rapidly expanded even as its tech peers Google and Facebook take most of the heat over user-privacy concerns. It’s important to remember, however, that no matter how many books or boxes of diapers Amazon sells, you are the company’s most valuable product.