A Chinese company that supplies touch screens to Apple has used thousands of minority laborers from the Xinjiang region under China’s forced labor program, according to a Tech Transparency Project investigation that raises new questions about Apple’s diligence in reviewing its supply chain.

Chinese government records, videos and local media reports show that the minority Uighurs were sent to work at the company, Lens Technology, by the same agency that supplied minority laborers to Nanchang O-Film Tech, another Apple supplier that was blacklisted by the U.S. last year over its participation in China’s forced labor program.

The new evidence, which TTP recently shared with the Washington Post, brings the number of Apple suppliers credibly tied to China’s repressive forced labor program to five.

TTP reported in August that Esquel, an Apple supplier of retail employee T-shirts, was blacklisted by U.S. authorities over its ties to coercive labor practices in Xinjiang. The Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), an Australian think tank, has previously reported that Foxconn Technology, Hubei Yihong Precision Manufacturing Co. Ltd and Hefei Highbroad Advanced Material Co. Ltd also participate in China’s forced labor program.

Taken together, the findings show that Apple’s links to forced labor in China are far more significant than the company has acknowledged to its customers and shareholders.

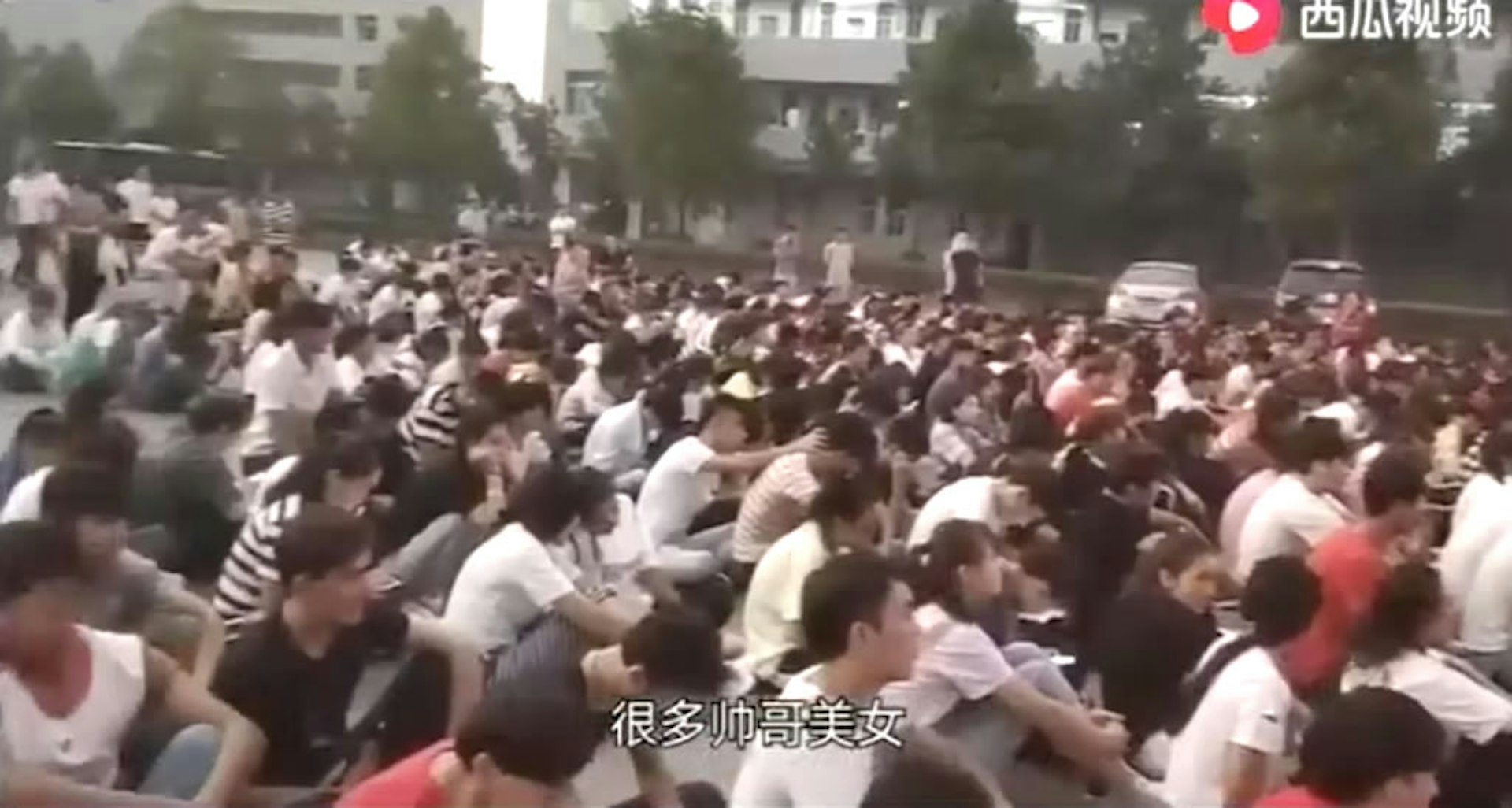

A local official in Xinjiang speaks toa group of identically dressed men and women waiting to board a train for inner China. The uncaptioned photo accompanied the Xinjiang–Suzhou Chamber of Commerce’s announcement about having sent over 4,000 people to inner Chinese factories over a year and a half.

Apple has repeatedly claimed to have audited its China supply chain and found it to be free of forced labor, an issue that plagues many companies that source parts and material from China. Asked about TTP’s evidence, "Apple spokesman Josh Rosenstock said the company has confirmed that Lens Technology has not received any labor transfers of Uighur workers from Xinjiang," according to the Post. Rosenstock did not specifically address images of Uighur workers at the Len Technology factory or other evidence.

Most of the records TTP identified were found through a Mandarin-language internet search, suggesting Apple’s investigations—or disclosures—have been incomplete.

Founded in 2003, Lens Technology found success making high-end glass screens for early mobile phones. But it was the company’s 2007 partnership with Apple that transformed Lens Tech into a tech giant in China. In early 2015, when the Chinese touch-screen maker listed on the ChiNext bourse in Shenzhen, some analysts worried it was overly reliant on a handful of clients—particularly Apple, which reportedly accounted for more than half its revenue.

Booming demand for smartphones and the success of the Apple Watch drove Lens Tech’s share price through the roof. The company’s founder, Zhou Qunfei, soon became the richest woman in China as of 2015. Her story captivated journalists, who wrote profiles describing how Zhou ascended from a poor migrant worker to the superstar head of a multibillion-dollar company through technical mastery and obsessive attention to detail.

A year after Lens Tech’s IPO, Apple crowed that the supplier’s “unprecedented commitment … to run its Apple operations on entirely renewable energy” was proof of Apple’s commitment to responsible manufacturing.

But over the following years, government records show Lens Tech was sent thousands of “transferred” minority workers from Xinjiang, the region in China’s far Northwest that has been the subject of an unprecedented crackdown on the local Uighur community that some describe as genocide.

As of 2018, the northern city of Turpan planned to send one thousand minority workers to Lens Technology, according to city’s Human Resources and Social Security Bureau.

TTP identified another 2,200 people from the Kashgar area who were sent to Lens Tech by an organization called the Xinjiang–Suzhou Chamber of Commerce, according to a media report. The Chamber has claimed credit for arranging the transfer of more than 4,000 “outstanding ethnic youth” and “minority masses possessing a certain level of quality” from Kashgar and Hotan Prefecture in Xinjiang to companies in inner China between 2017 and August 2019.

Eighteen hundred of these workers from Hotan went to the Apple supplier O-Film, according to the Chamber. That number roughly corresponds to those identified by ASPI, the Australian think tank that has reported on Apple’s role in China’s forced labor program.

Lens Tech appears to have received workers from Xinjiang’s Hotan Prefecture as well. In late February 2020, at the height of the coronavirus pandemic in China, the China Civil Aviation Network reported on hundreds of locals boarding chartered flights from Hotan and Kashgar to Hunan in order to return to work in Lens Tech’s factories and “fight the epidemic.” (The article and accompanying photo were taken down after it was cited by the Washington Post.) The workers had likely returned home to Xinjiang while Lens Tech was shut down for the Chinese New Year holiday and been stranded when the transportation network was shut down to prevent the spread of Covid-19. The reports said that the workers were typically under 20 and that many had already been working at Lens Tech for two years.

A photo posted to Chinese media shows a plane full of Uighur laborers retuning to work at Lens Tech amid the Covid-19 outbreak in China.

The Xinjiang–Suzhou Chamber of Commerce’s announcement was steeped in the language of “poverty alleviation,” the official bureaucratic rationale of China’s forced labor programs. The Chamber extolls its own hard work, “willingness to suffer, stoicism in the face of adversity,” and “unstinting perseverance” in the face of numerous, unspecified obstacles to addressing the issue of “severe poverty among the excess labor” in southern Xinjiang.

Such transfers of Uighur workers from Xinjiang to other regions of China are often, if not always, forced or coerced, according to human rights groups and academics interviewed by the Post. The materials uncovered by TTP included the first direct evidence that the Chinese government uses a surveillance database known as the Integrated Joint Operations Platform as part of its forced labor program, Darren Byler, an anthropologist at the University of Colorado at Boulder, told the Post.

China often describes the forced labor program as an effort to build job skills for underemployed minorities. This ostensible benevolence is belied by the Associated Press’s reporting on coercive conditions at O-Film, which operates one of the factories that received the workers, and by language in the announcement itself, which expresses gratitude to local Public Security Bureaus in Xinjiang.

The Chamber itself noted that militant nature of the transfers:

Young Xinjiang people arriving in a new place will encounter much that they are unaccustomed to and not adapted for, so it is necessary to have centralized management with organization, discipline, regulations, and a bottom line. In the years that the Chamber has been sending groups of young people to inner China, the Chamber has implemented military-style management, with excellent results that have been affirmed by the host inner China businesses. On the basis of teams sent by relevant departments in Xinjiang, the Chamber has sent three-to-five-person logistics-support teams to ensure the Xinjiang workers’ room and board and assist the managing cadres in establishing management.

新疆青年到异地就业有诸多不习惯、不适应,必须要统一管理做到有组织、有纪律、有规章、有底线。近几年有几批青年到内地就业后,商会都进行准军事化管理,效果很好,受到接纳企业的肯定。在新疆相关部门派出随队管理干部的基础上,商会选派3-5人组成后勤保障组,保障新疆籍员工的饮食起居并协助管理干部抓好管理。

In October 2019, a labor recruiter posted a video online showing “Lens Tech Uighurs celebrating National Day.”

The video, which has since been removed from the internet, shows dozens of people sitting or squatting on the ground in front of Lens Tech’s cafeteria as a man speaks into a microphone. Though the audio of the speech has been replaced by pop music in the video, as the camera pans over the crowd it is possible to read one of the red and yellow banners hung over the courtyard: “All Workers Sent by the Kashgar Region Human Resources and Social Security Bureau to Lens Technology: Welcome National Day – Sing Red Songs – Be Grateful to the Party.”