A year after a gunman used Facebook to livestream a mass shooting in Christchurch, New Zealand, that left 51 people dead and sparked an international outcry over violence on social media, videos of the massacre can still be found on Facebook today.

The Tech Transparency Project (TTP) identified eight versions of the attack video on Facebook. All of them indicate they’ve been active since shortly after the shooting on March 15, 2019.

The continuing presence of the horrifying images on the social network—12 months after Facebook first outlined the steps it was taking to remove the videos—highlights the company’s inability, or unwillingness, to rid its platform of gruesomely violent and hateful content, even in cases that have attracted intense global scrutiny.

Following the Christchurch attack, Facebook Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg said people have “rightly questioned how online platforms such as Facebook were used to circulate horrific videos of the attack,” adding, “We have heard feedback that we must do more – and we agree.”

But the New Zealand shooting shows that even when Facebook knows what it’s looking for—in this case, a specific video image—the artificial intelligence systems that it so often touts as the answer to its content woes have failed to do the job.

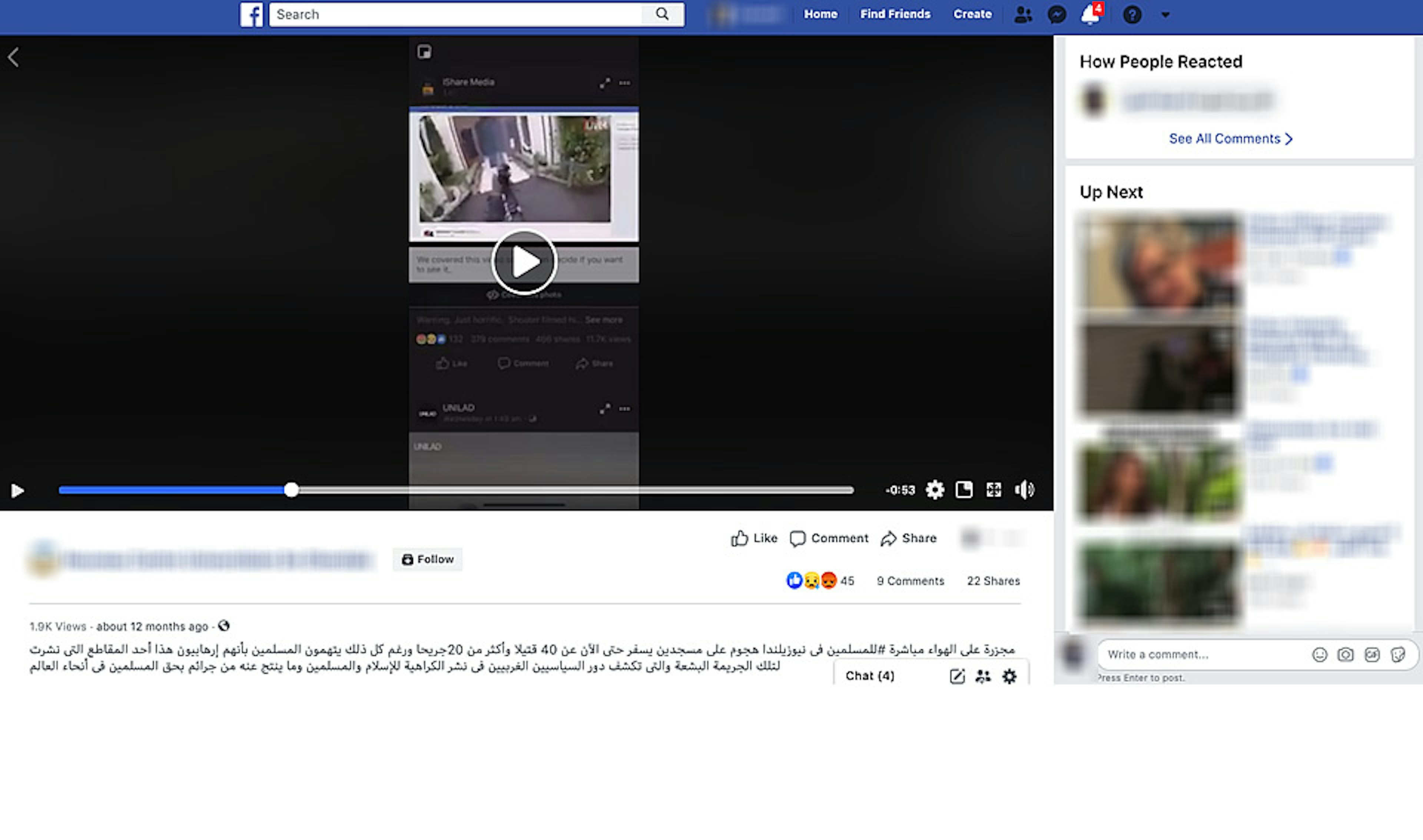

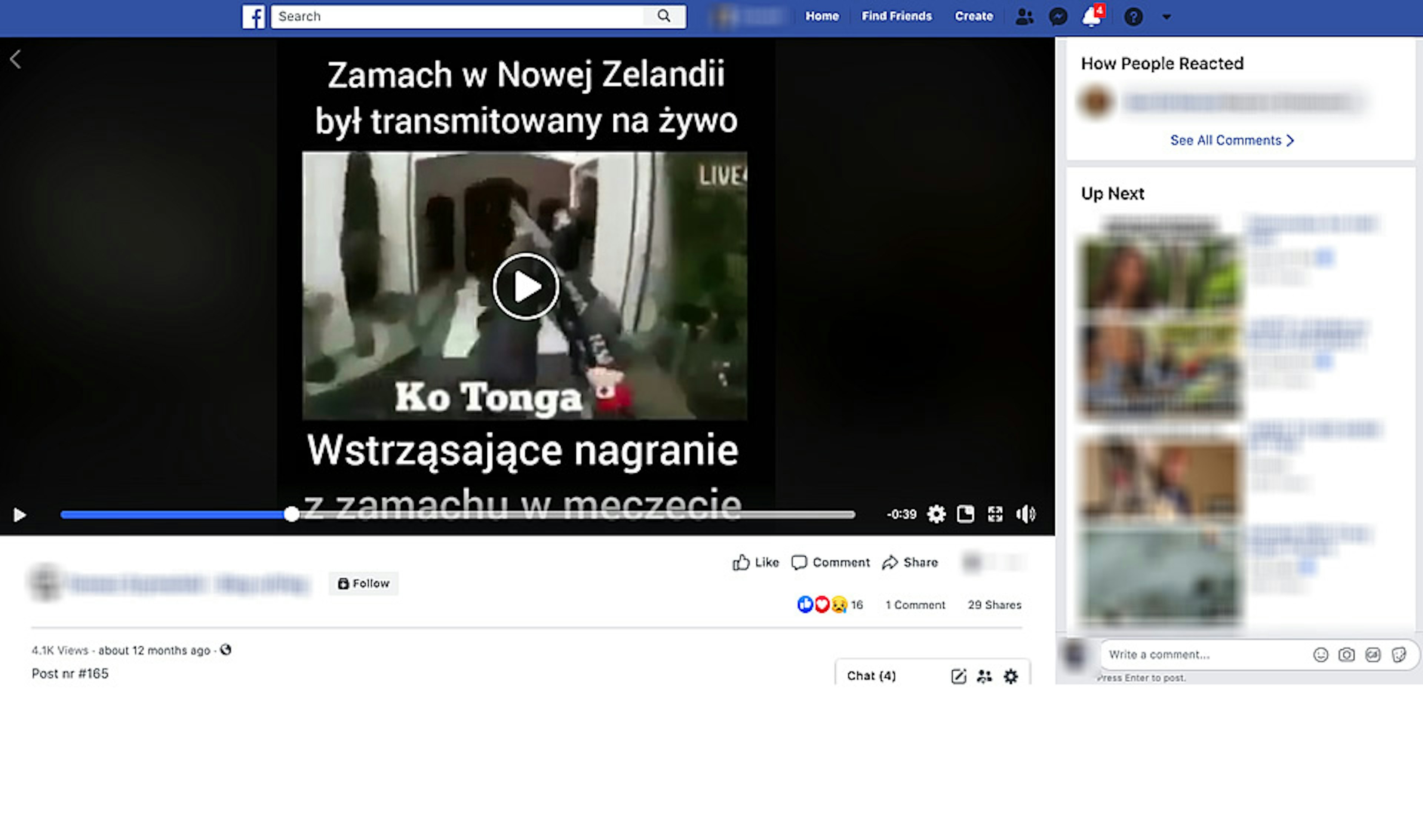

Slides of Christchurch videos (screenshots)

Slides of Christchurch videos (screenshots)

The Christchurch massacre—in which a heavily armed man with a helmet-mounted camera livestreamed his killing spree in a pair of mosques—was New Zealand’s worst-ever terrorist attack. Facebook removed the stream after it ended, but not before it was replicated and spread across the social network and the broader internet, including YouTube, Twitter and Reddit.

Three days after the mass murder in New Zealand, Facebook said it removed 1.5 million copies of the video in the first 24 hours after the massacre, the vast majority of them before they were uploaded to the platform. The company also said it “hashed” the video, so that visually similar videos could be detected and automatically deleted.

Facebook later said it had removed 4.5 million pieces of content related to the attack.

A year after the Christchurch shooting, however, TTP was able to identify eight videos of the massacre that are still available on Facebook. All are clips of the livestream, and some come from foreign language Facebook accounts in Polish, Arabic and Turkish.

Two of the videos are preceded by an advisory that warns, “This video may show violent or graphic content,” but Facebook allows users to view them anyway.

Some of the clips appear to be recorded off the screen of another device. They range in size, and some are manipulated, with music added, for example. At least one is sped up, and one is in black-and-white. Altering a video through editing is one way people try to evade automated systems tasked with taking down content.

This is not the first time Christchurch attack videos have been found on the platform long after the massacre. In September 2019, six months after the shooting, NBC News reported the existence of more than a dozen of the videos on Facebook.

The New Zealand shooter allegedly posted an anti-Muslim, anti-immigrant manifesto on social media prior to the attack, and Facebook, in the wake of the shooting, banned white nationalist and white separatist content. The company later endorsed the “Christchurch Call,” an effort led by New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern and French President Emmanuel Macron to curb the spread of terrorist material online.

Under the set of non-binding Christchurch Call commitments, online service providers like Facebook pledged to take “specific measures seeking to prevent the upload of terrorist and violent extremist content and to prevent its dissemination on social media and similar content-sharing services.”

Around that time, Facebook also announced it would apply a “one strike” model to Facebook Live, restricting anyone who violates the platform’s “most serious policies” from using the livestreaming feature for a period of time, such as 30 days.

The company later said users in Australia and Indonesia who search for hate-related terms would be directed to local organizations that work to reorient people away from extremism and terrorism, similar to a Facebook initiative in the U.S. Brenton Tarrant, the Australian accused of carrying out the Christchurch shootings, is expected to proceed to trial in New Zealand in June.

But even as the accused gunman prepares to face prosecutors in court, videos of his attack continue to circulate on Facebook—a troubling reminder of the social network’s unsuccessful efforts to clean up its platform.