So-called coyotes who smuggle undocumented migrants across the U.S. border—and scammers pretending to be coyotes—are finding creative ways to use Facebook, WhatsApp, and TikTok to reach potential customers, according to a Tech Transparency Project (TTP) investigation that highlights how the tech platforms are supercharging the migration economy.

TTP surveyed more than 200 migrants this spring about how they get their information, and our analysts joined and followed their social media sources, including groups, pages, and chats. The review found an abundance of advertising by coyotes, who make full use of the online tools available on the platforms to promote their services.

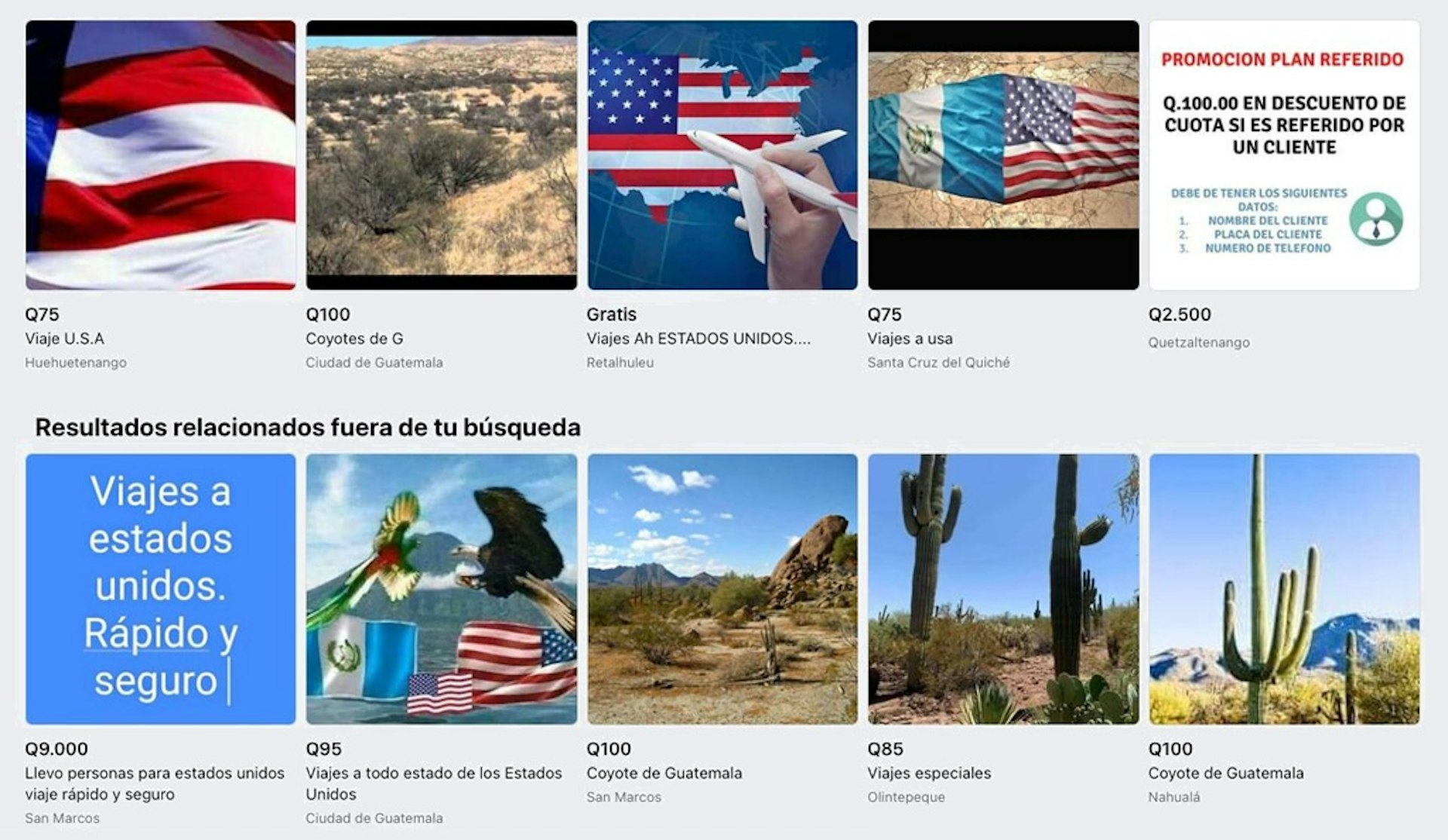

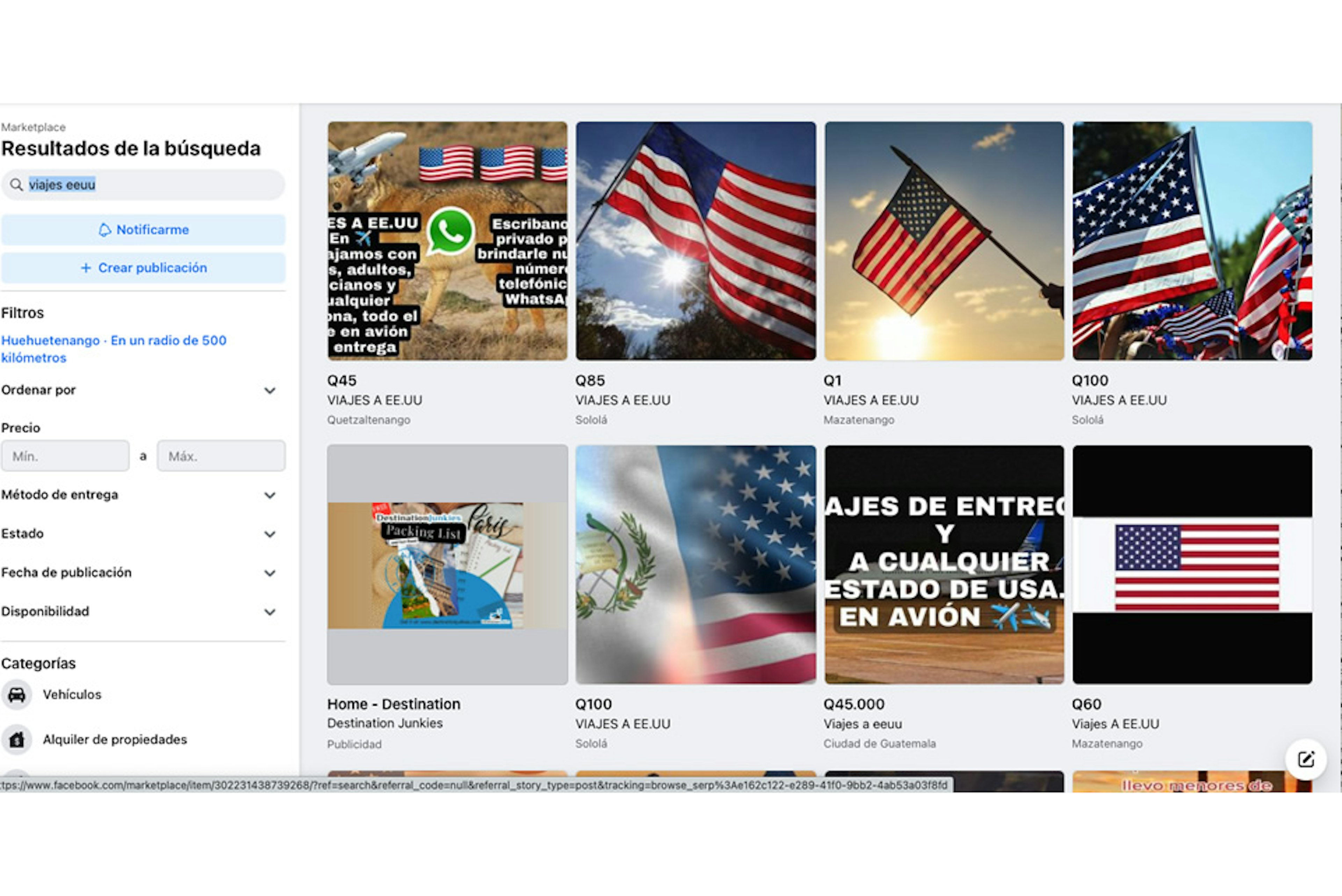

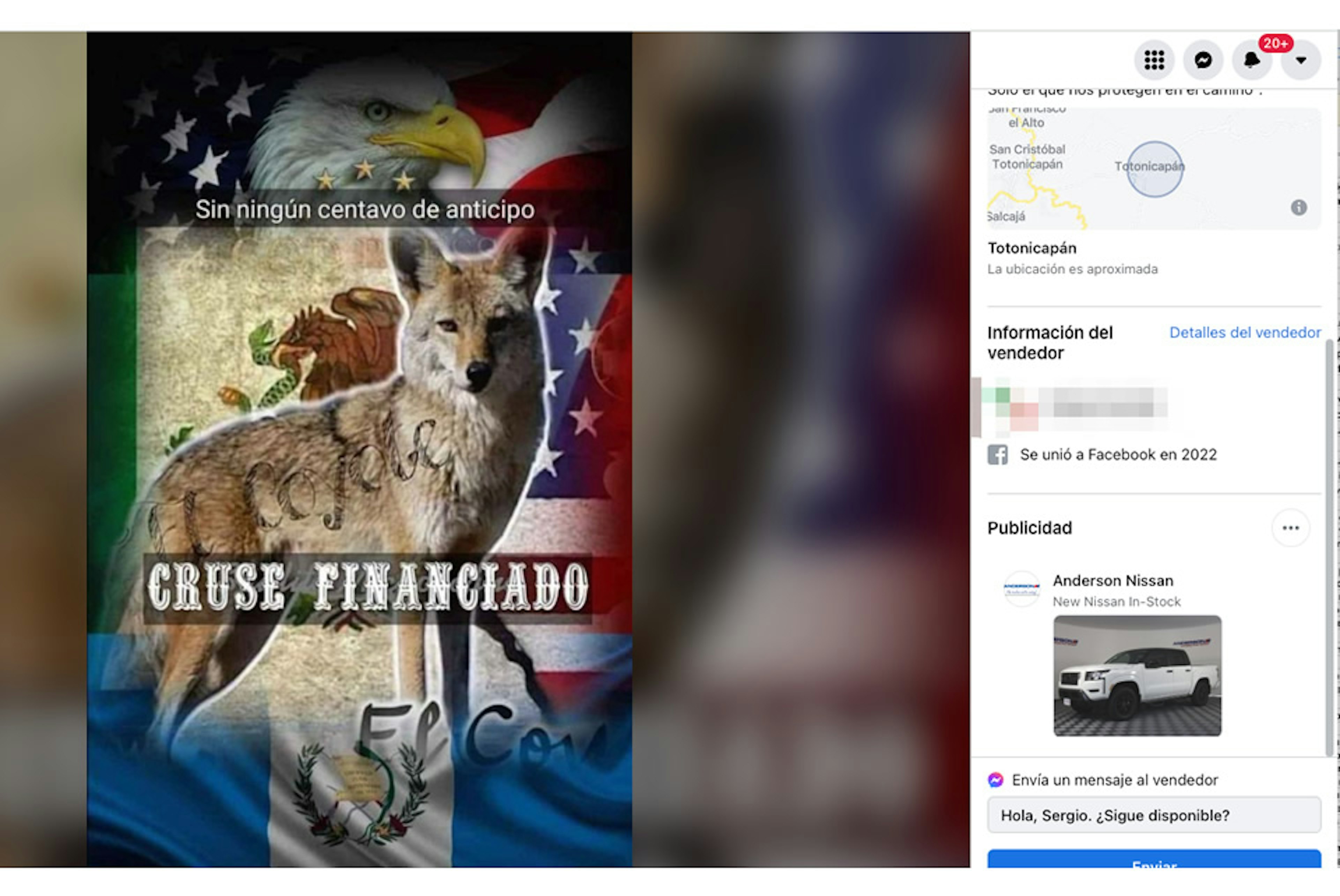

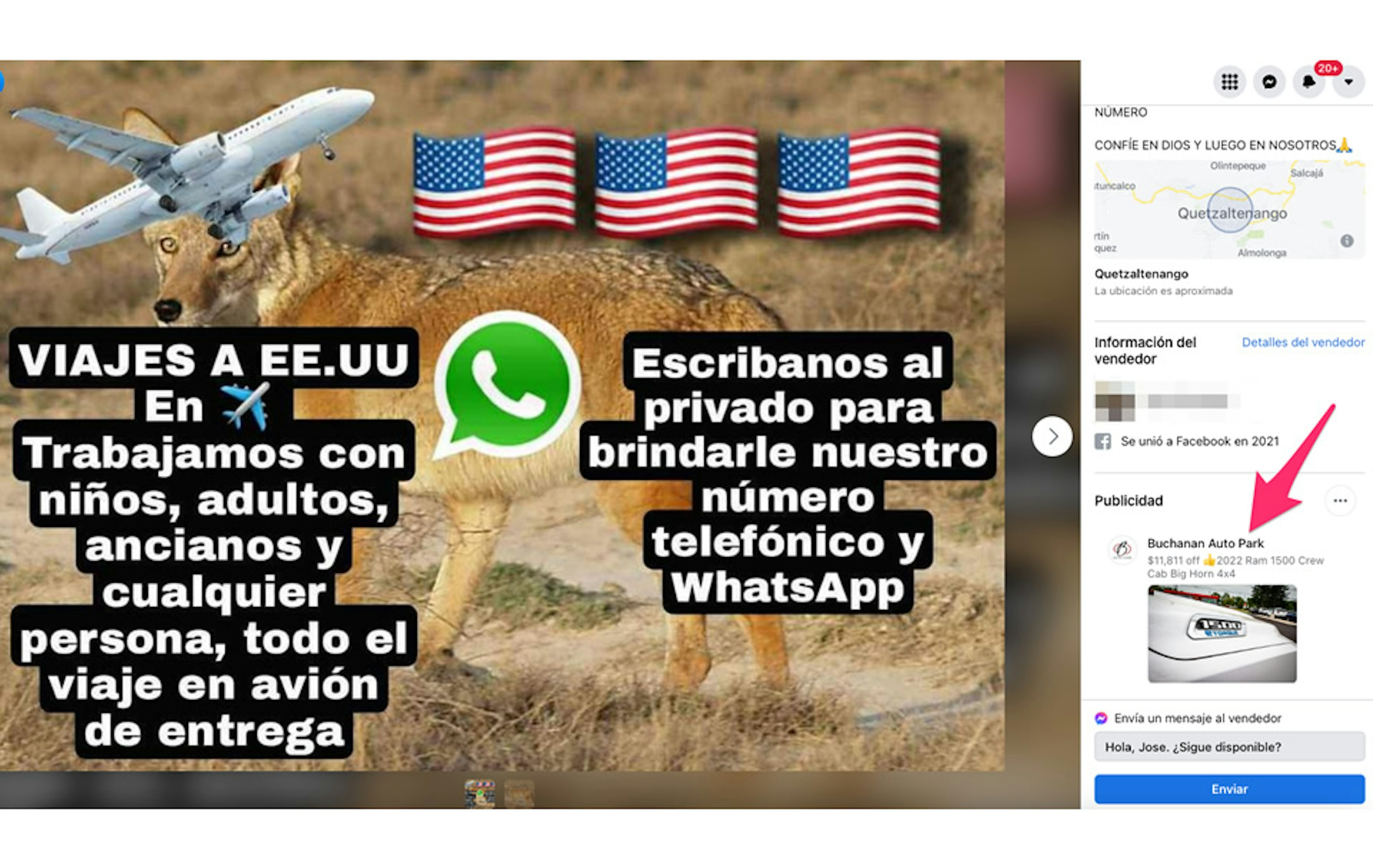

For example, coyotes frequently advertise on Facebook Marketplace as well as local buy-sell groups on Facebook, where their offers to take people across the border mingle with ads for things like motorcycles and used cell phones. In this way, the coyotes can reach people before they have even decided for certain that they will migrate, and give them the false impression that arranging a trip to the U.S. is as easy as ordering household products online.

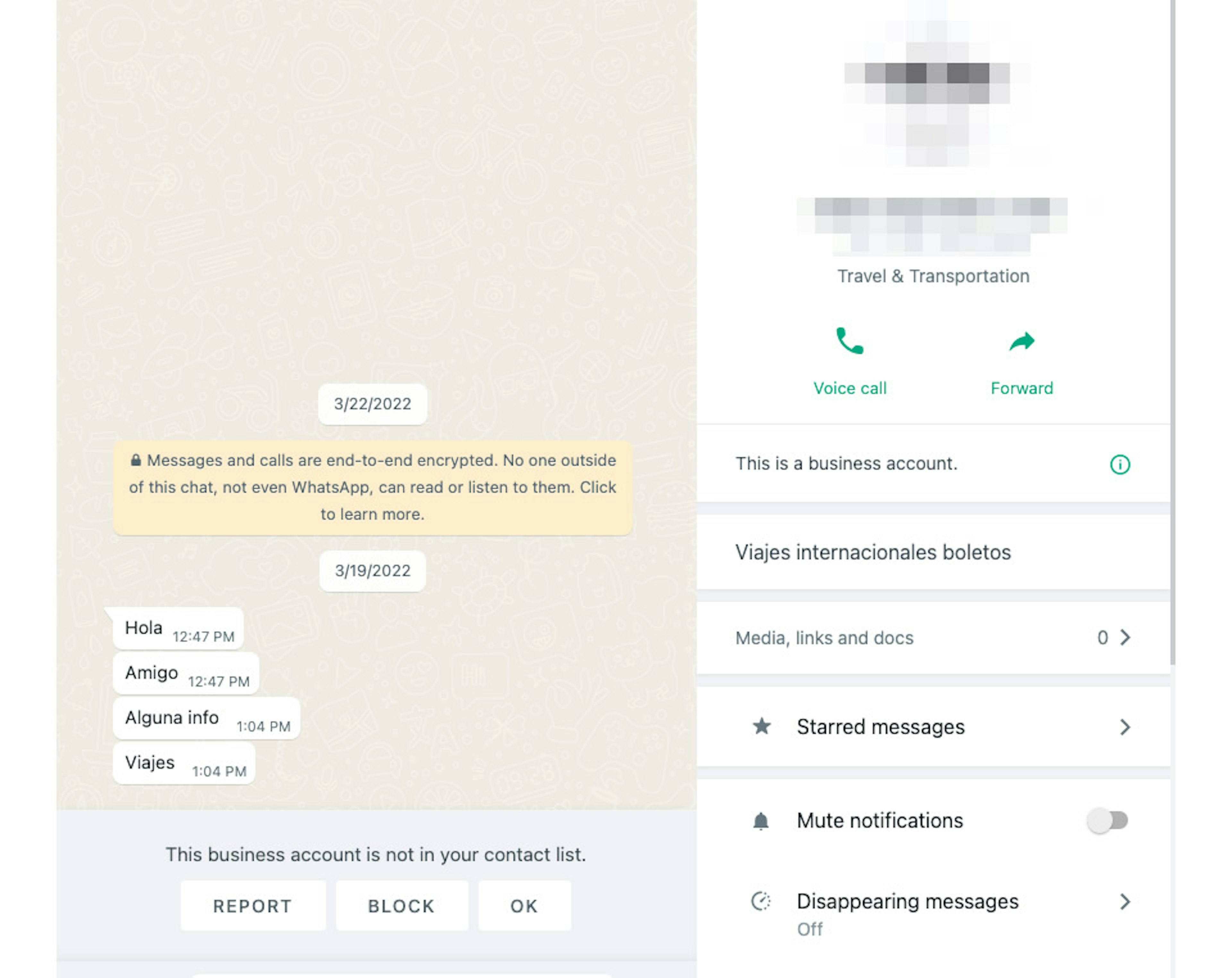

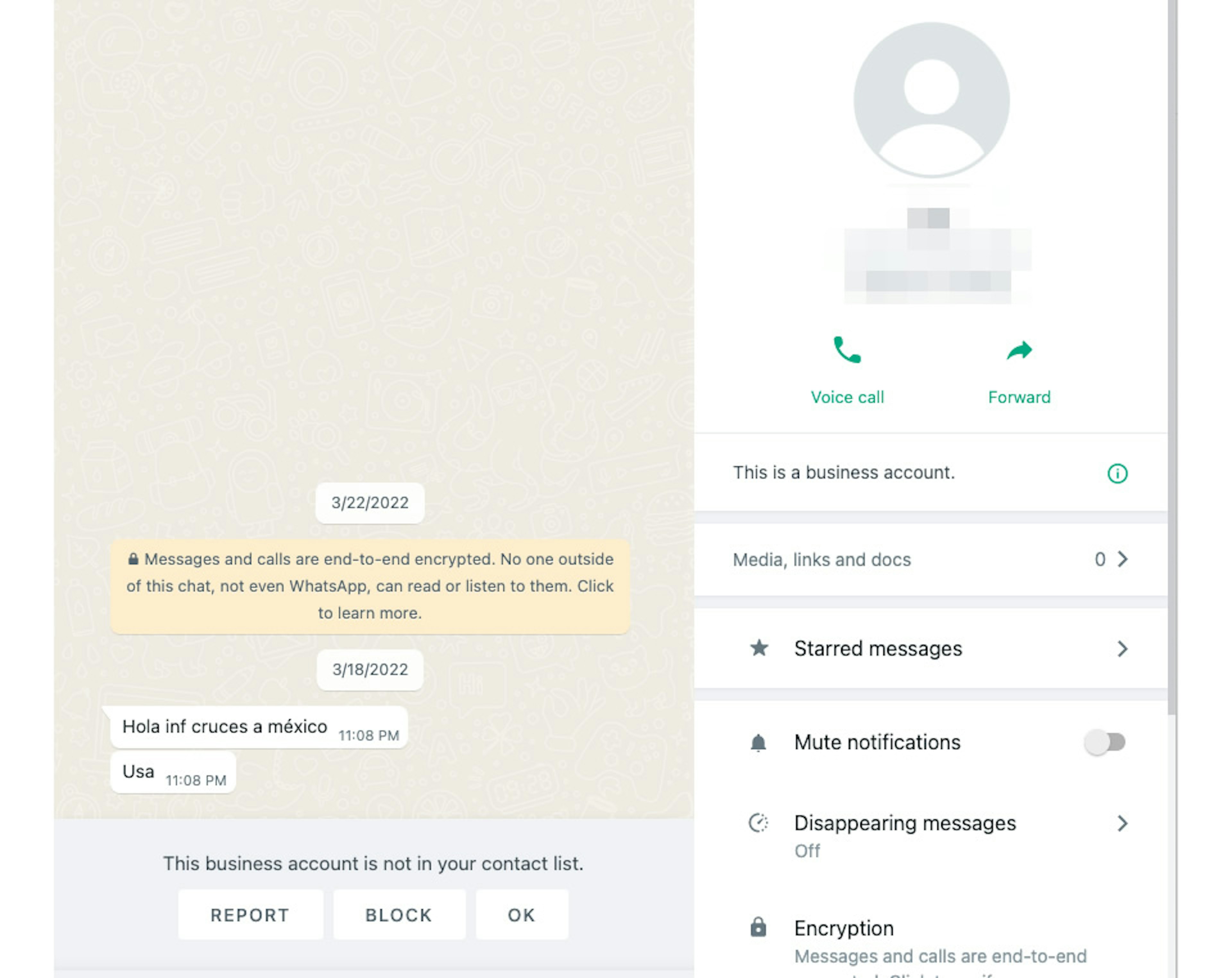

The investigation also found that many coyotes rely on WhatsApp to communicate with migrants, and even use WhatsApp business accounts, which allow them to broadcast messages to a large number of people and provide a “catalog” of different services. (WhatsApp, like Facebook, is owned by Meta.)

This activity is occurring despite Meta’s policy prohibiting content that offers to provide or facilitate human smuggling. In some cases, Facebook served ads into coyote posts, showing how the platform profits from advertising that violates its policies.

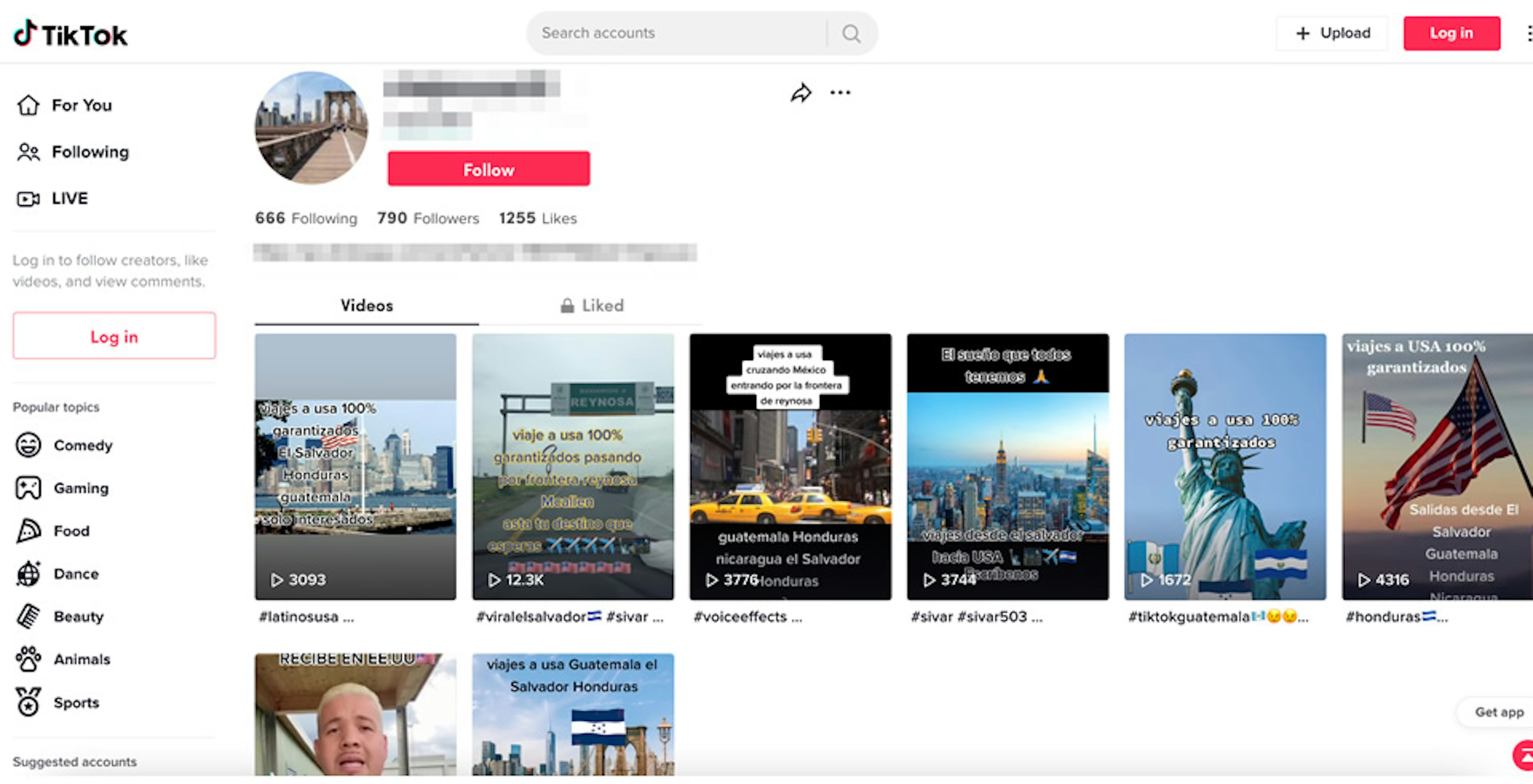

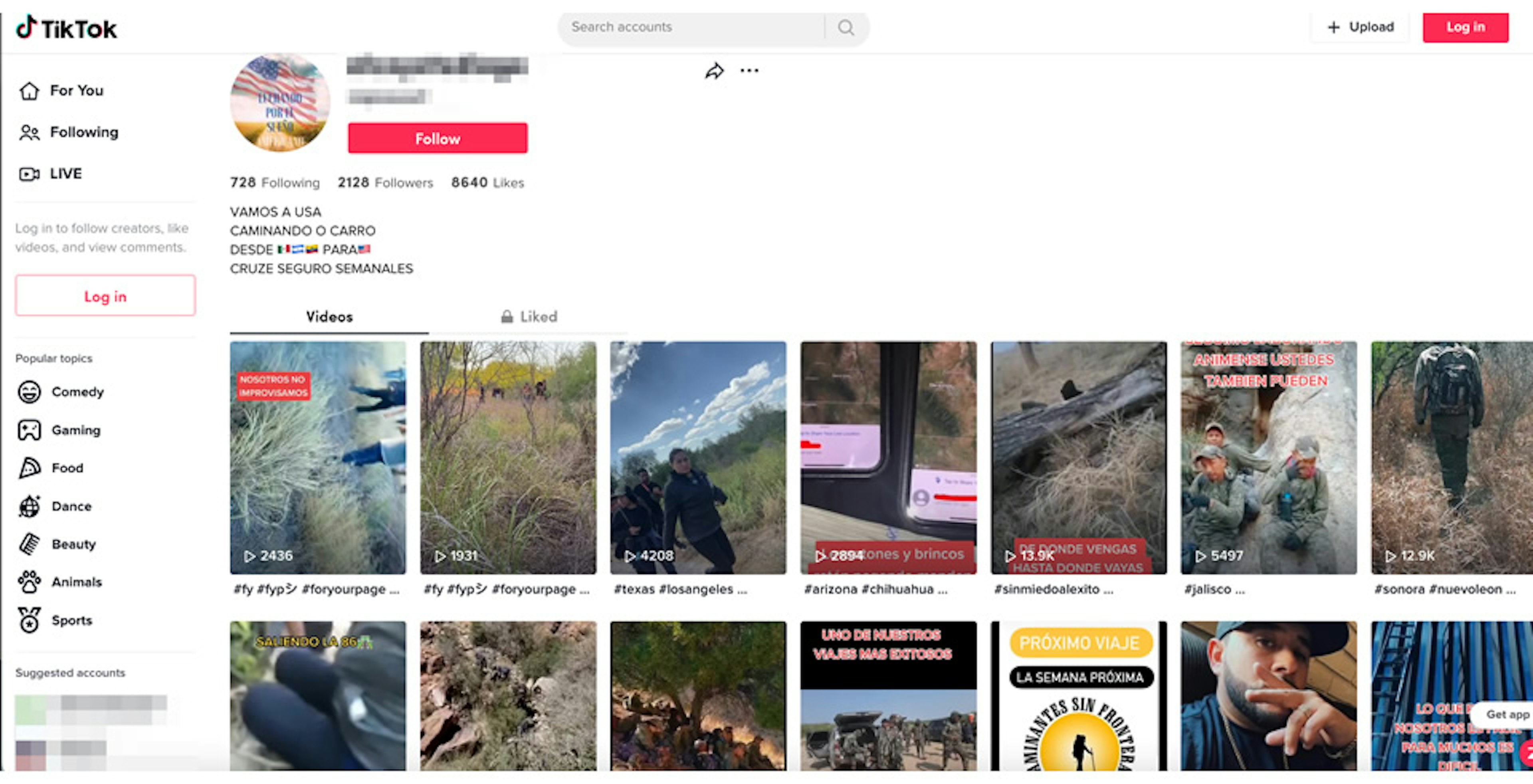

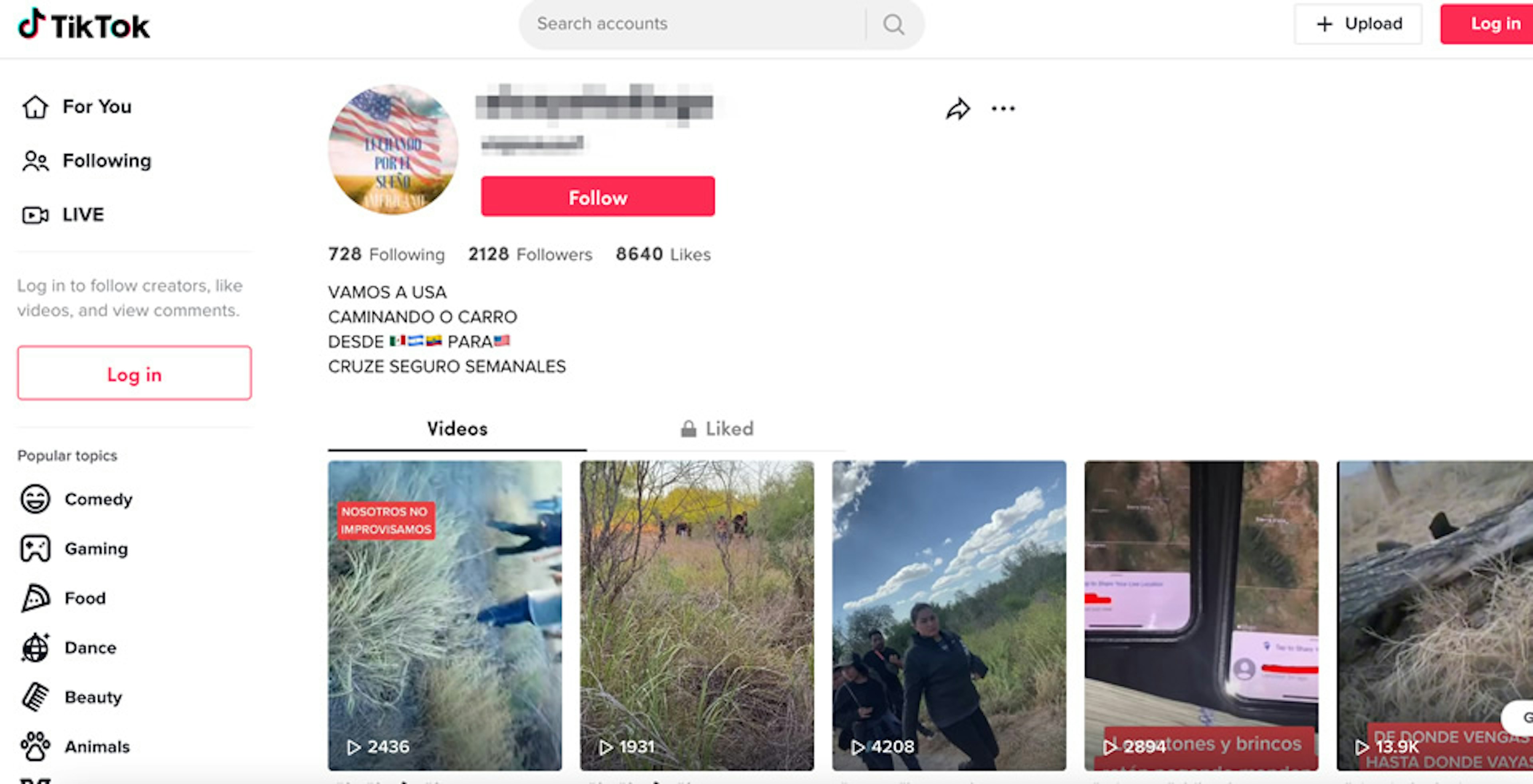

Meanwhile on TikTok, TTP found that coyotes freely advertise passage to the U.S., often offering their services in text over banal videos of people performing landscaping or construction jobs with no obvious link to migration. TikTok’s content policy prohibits posts promoting “human smuggling.”

The tech platforms’ laissez-faire approach to content moderation allows coyotes to exploit these tools to work more efficiently—and reach greater numbers of migrants desperate to make the journey north. That in turn creates more opportunities for migrants to get scammed, extorted, or kidnapped, as the journey across Mexico becomes more treacherous.

Undocumented migration is such a big business in some communities that ads run on local radio in Spanish and Mayan dialects offering weekly guided trips to the U.S. border. Like the ads on Facebook, these radio spots promise “financed and secure” trips to the United States.

Increasingly, violent cartels have taken over the illegal migration business, squeezing out freelance coyotes who relied on reputation to keep their businesses afloat. These cartels often lure migrants in with the offer of coyote services, and then kidnap and extort them once they are far from their home communities. Several migrants who participated in TTP’s survey had either experienced this for themselves, or knew someone who had.

Platforms like Facebook allow cartels to pose as solo practitioners while communicating with many potential migrants at once. One coyote account identified to TTP by a Guatemalan migrant had posted the same ad in dozens of buy-sell groups all over the country, suggesting a larger network behind the supposed solo practitioner.

It is nearly impossible to distinguish genuine social media posts offering migration assistance from scams seeking the anonymity afforded by digital media. Multiple survey respondents told TTP interviewers that they had been misled by coyotes they met online. “Previously I traveled alone and I relied on a Facebook account for support, but they cheated me," one migrant said. "[That account] only exists to scam people."

The platforms have made no apparent move to protect migrants from these scammers. Instead, they provide unscrupulous actors with every tool that they need to make victims out of vulnerable people seeking a better life.

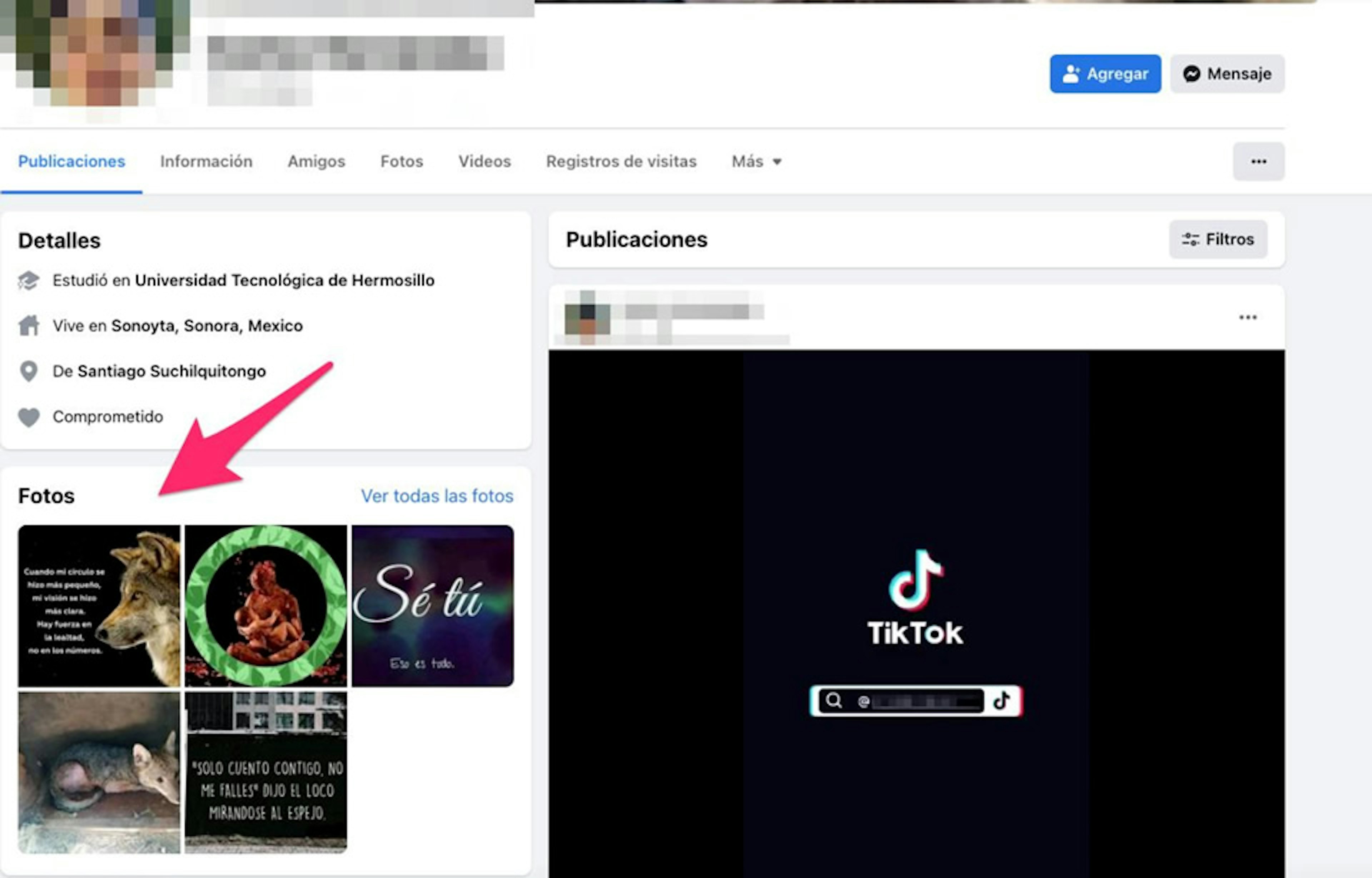

Several migrants told TTP that they found their coyotes, or scammers posing as coyotes, through Facebook. One survey respondent who had yet to depart Guatemala identified his coyote’s Facebook account to interviewers, noting that he found the individual through a local buy-sell group. TTP analysts found that this account has posted dozens of ads for coyote services in similar groups across Guatemala.

The ads not only promoted “safe and financed” trips to the United States, but also promised to connect respondents with jobs in their new country. Commenters on some of these ads pointed out that the ads were likely a scam. “Be very careful, those who offer your work on face are kidnappers,” one commenter wrote.

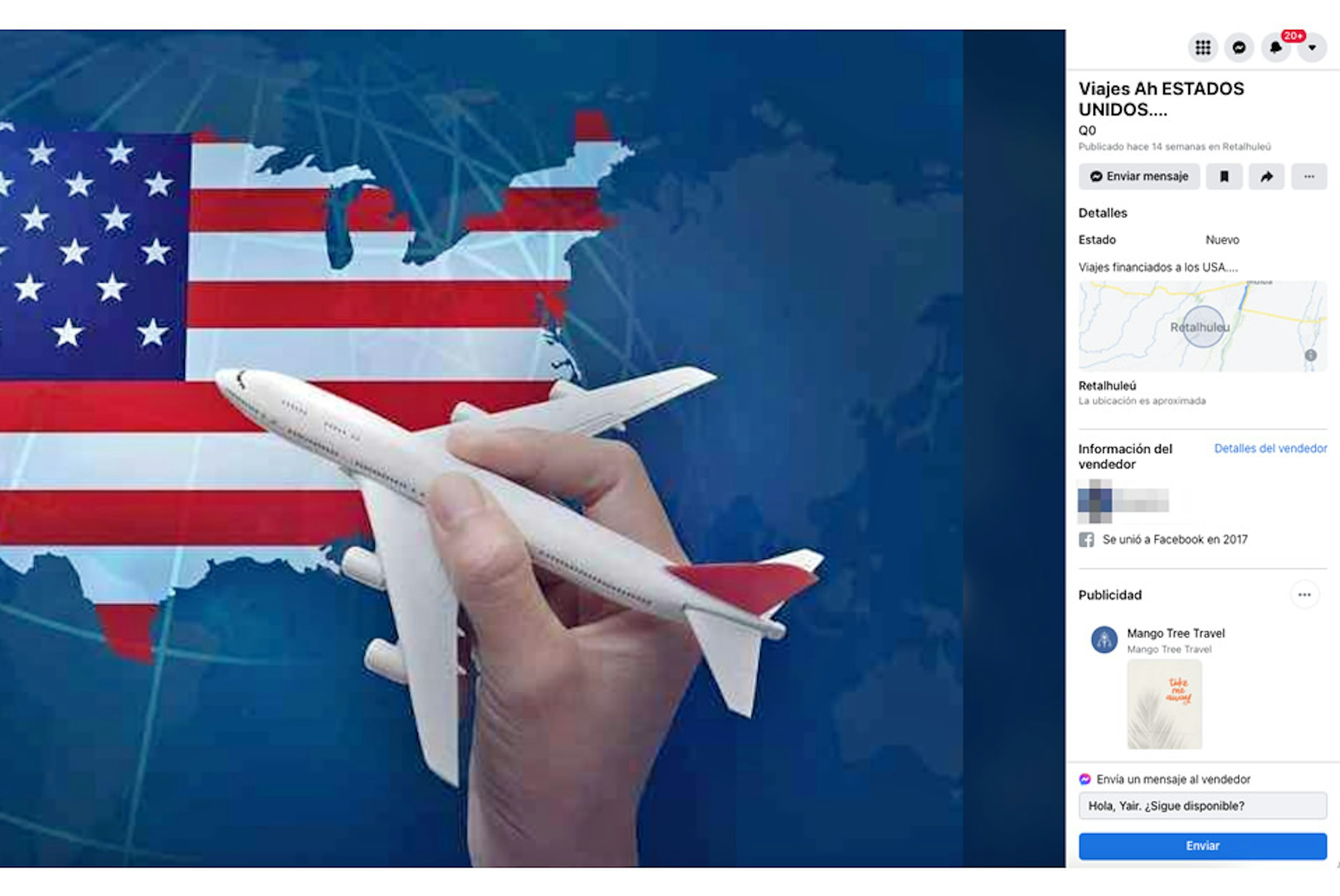

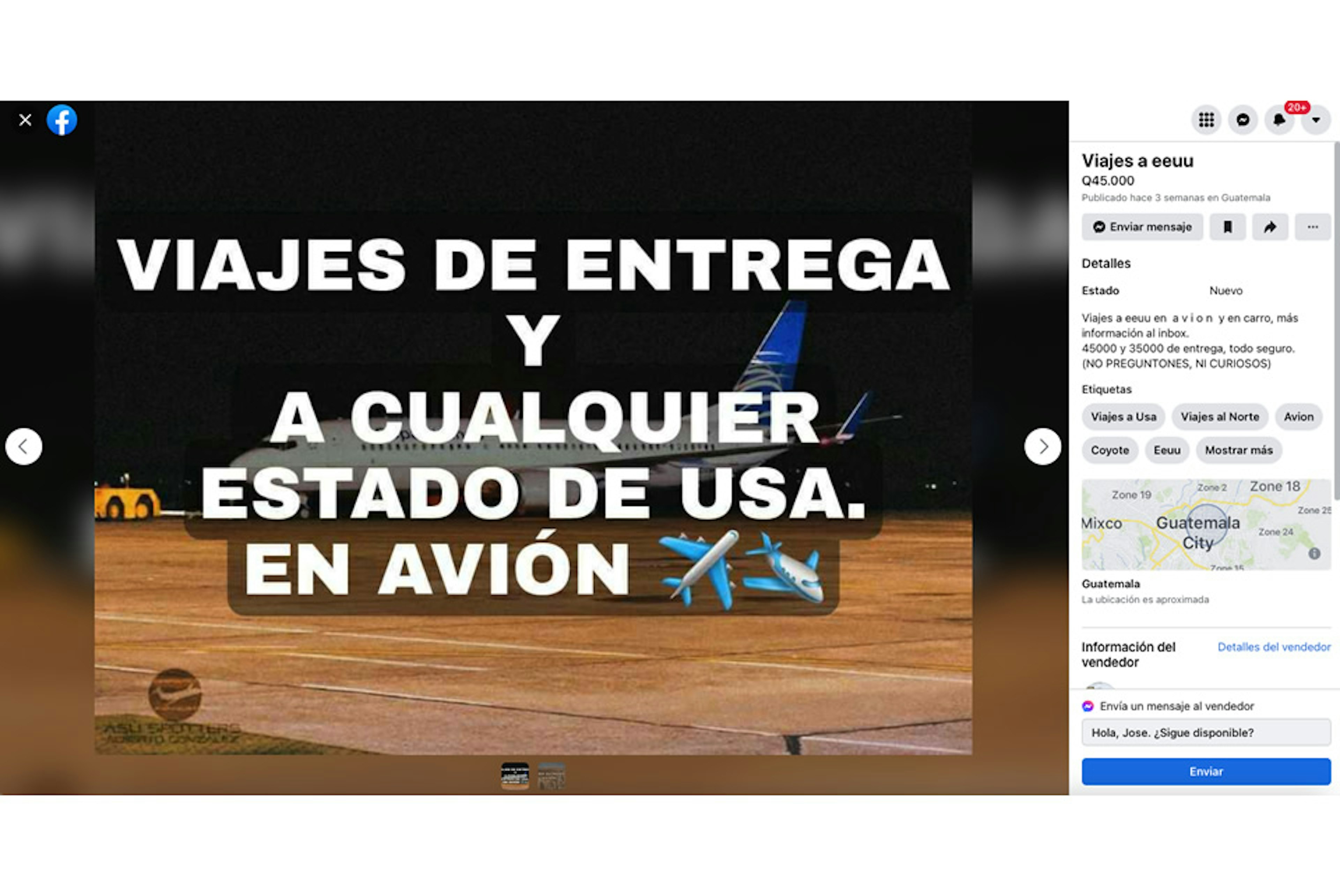

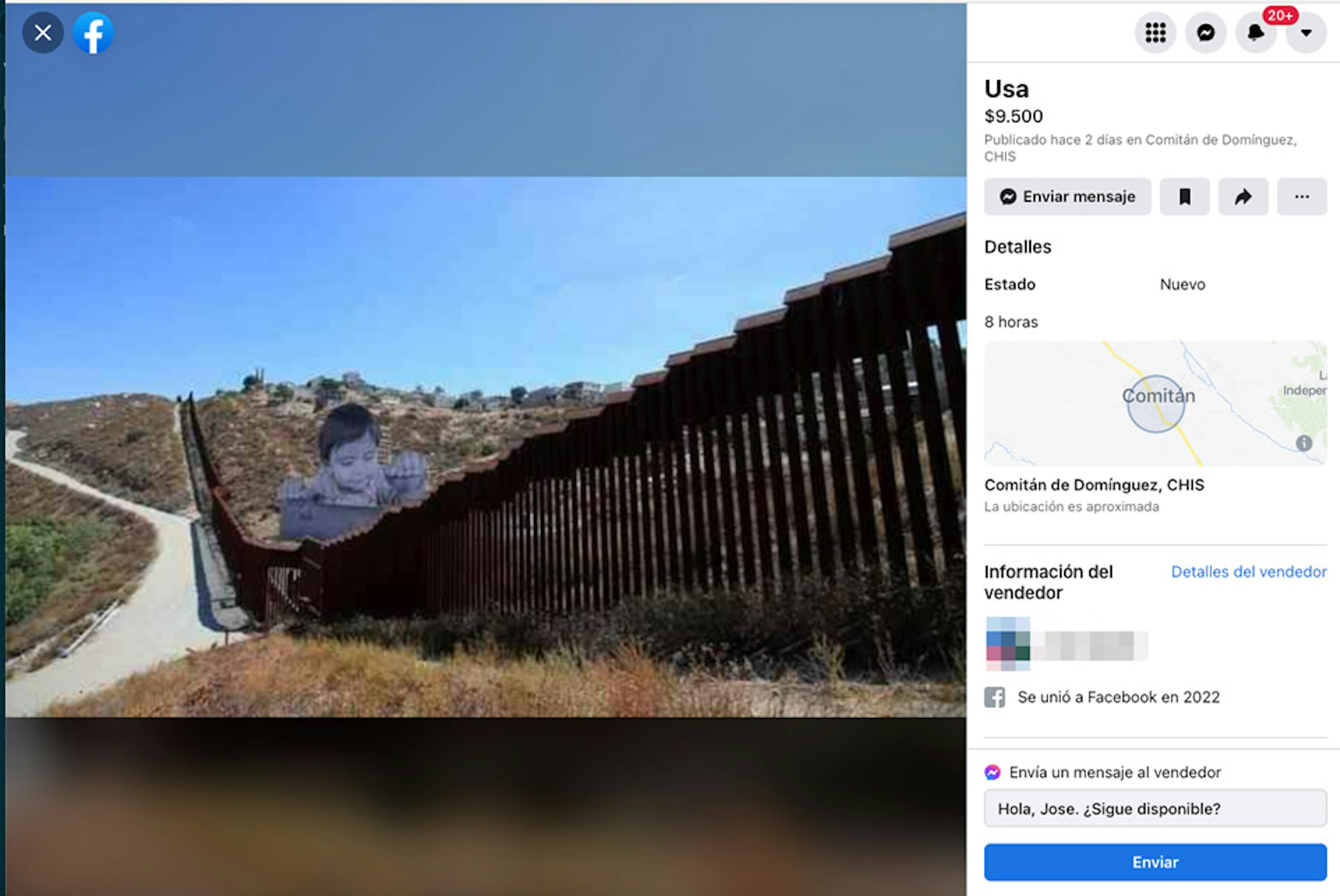

A review of Facebook Marketplace and local buy-sell groups reveals that ads like these are common. Some ads openly advertise coyote services in the title of the listing or in tags on the post. Other ads are coy, advertising trips to the U.S. alongside photos of a coyote (the animal version) or border fence. Still others look like generic travel ads, making only winking reference to the true nature of their services.

Facebook’s Marketplace tools make it easy to locate and communicate with coyotes advertising on the platform. All Marketplace posts have an embedded messaging feature allowing a viewer to contact the person posting the ad. Others have embedded links to WhatsApp.

Earlier this year, conservative media outlets expressed outrage over an internal policy memo obtained from Meta that allegedly stated that the company would allow posts that solicit help crossing borders illegally. The internal policy showed leniency toward migrants seeking coyote services, but the platform has consistently prohibited ads, like the ones above, offering so-called human smuggling services. Facebook’s human exploitation policy prohibits “content that offers to provide or facilitate human smuggling,” which it defines as “the procurement or facilitation of illegal entry into a state across international borders.” The policy says “without necessity for coercion or force, [human smuggling] may still result in the exploitation of vulnerable individuals.”

Facebook not only fails to remove these policy-violating posts from potentially exploitative coyotes; it also monetizes them. Many of the Marketplace posts promoting coyote services analyzed by TTP had third-party ads for legitimate businesses embedded within them, allowing Facebook to make money every time a migrant looks for coyote services on the platform. Some of the posts even featured an ad for a scholarship program run by Facebook’s parent company.

Many of the Facebook ads for coyote services encouraged viewers to contact the advertiser via WhatsApp. In addition to phone numbers, some coyote ads on Facebook feature custom links that automatically launch a private WhatsApp chat with the seller. WhatsApp messages are direct, encrypted communications not governed by a content policy. This makes it difficult to identify and track bad actors who seek to exploit migrants using the platform.

WhatsApp also makes it easy for coyotes—and scammers—to contact potential marks. TTP’s test WhatsApp account, which never sent outgoing messages to any other users, received several direct messages from individuals appearing to offer coyote services.

Several of the WhatsApp users who made these unsolicited offers were business accounts, which allow users to broadcast messages to a large number of users, advertise products and services in a “catalog,” and post cross-platform ads with custom links that launch a WhatsApp chat with the seller.

TikTok

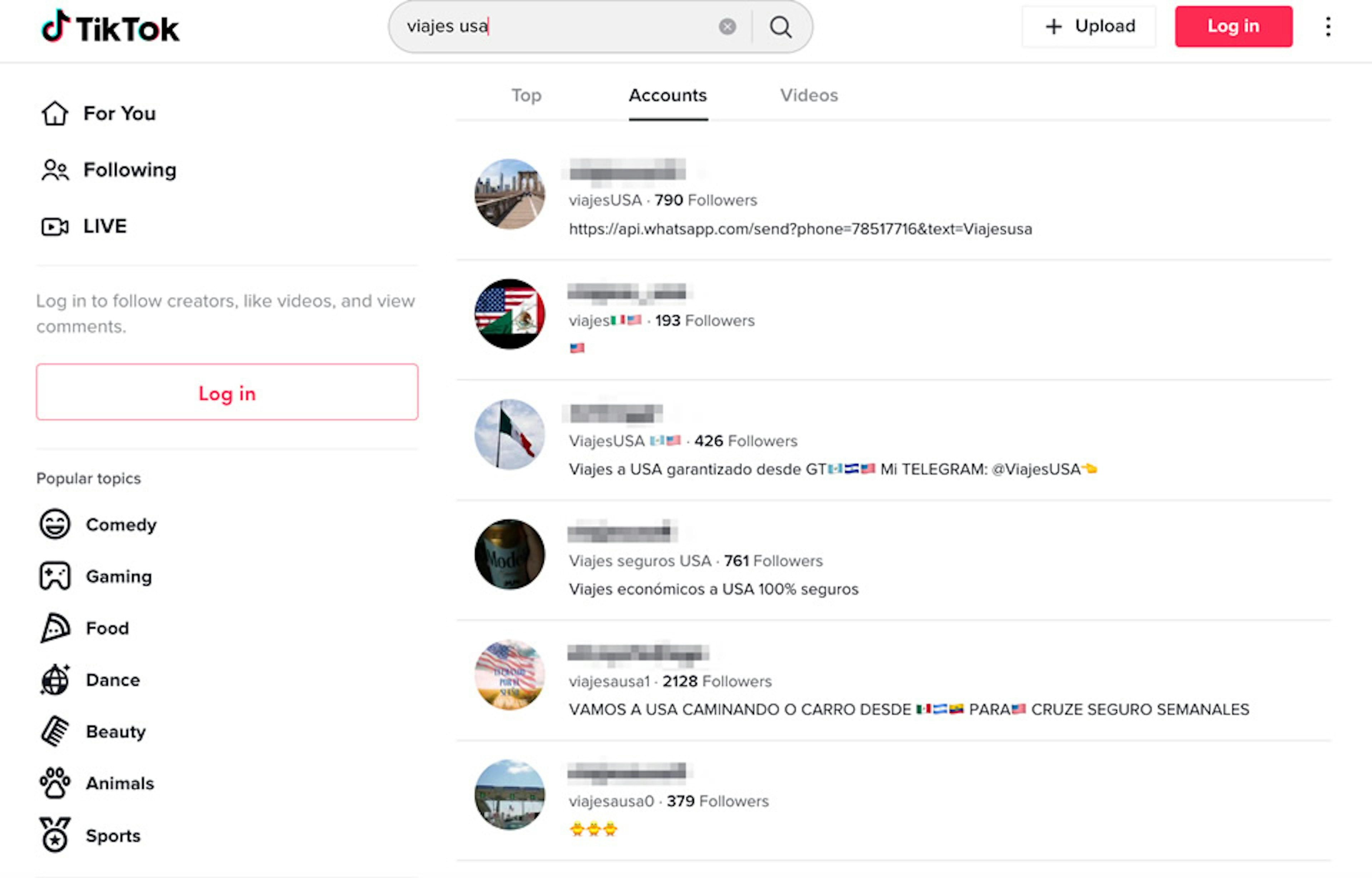

Coyotes often advertise across platforms to reach a broader audience. Links to TikTok were scattered throughout the migrant-focused Facebook and WhatsApp groups identified by respondents, and TTP identified a robust community of coyotes advertising on the video platform, whose audience skews younger. Some migrants told TTP interviewers that they didn’t find the video platform trustworthy, but a handful of respondents said that they had found migration services through TikTok.

On TikTok, coyotes freely advertise passage to the U.S., often advertising their services in text over banal videos with no obvious link to migration. TikTok’s content policy prohibits posts promoting “human smuggling,” but a search for “viajes usa” (USA trips) yields dozens of accounts advertising these services.

These social media platforms give coyotes and bad faith actors seeking to exploit migrants the ability to reach a wider audience with greater anonymity than ever before. Platform tools make it easy to contact, extract payment from, and deceive vulnerable people seeking passage to the United States. Far from providing quality information about their options when weighing the risky decision to travel abroad, platforms have left migrants on their own to sort out the good coyotes from the bad.