Facebook has repeatedly failed to remove “boogaloo” extremists who are using the platform to plan for a militant uprising—an alarming illustration of the company’s broader problems dealing with dangerous content, according to a Tech Transparency Project (TTP) review.

TTP first warned about private Facebook boogaloo groups in April, documenting how members were using them to organize for a coming civil war and share tactics on things like explosives and flame throwers. Following TTP’s report, Facebook said it had taken down groups and pages that use “boogaloo” and related terms and would “enforce against any violations.”

But in the months that followed, as reports emerged of Facebook boogaloo group members plotting or engaging in real-world violence, it became clear that Facebook had not adequately addressed the problem. The company scrambled a series of announcements in June, pledging to make it harder to find boogaloo groups and pages on Facebook and banning what it called a “violent” boogaloo network.

Despite those measures, TTP found that Facebook has consistently failed to spot boogaloo activity and missed boogaloo groups’ simple name changes designed to evade detection. Facebook’s spotty track record in removing these extremists, despite intense media attention on the issue and pressure from lawmakers, provides a window into Facebook’s deeper dysfunction policing its platform for things like hate speech and misinformation.

Here are some of the highlights from TTP’s review:

- TTP identified 110 Facebook boogaloo groups that were created since June 30, when Facebook announced it was banning a “violent” boogaloo network. At least 18 of the groups were created on the same day as Facebook’s announcement.

- Many boogaloo groups have easily evaded Facebook’s crackdown by rebranding themselves, often co-opting the names of children’s movies, news organizations and even Mark Zuckerberg. Some of the newer groups already have more than 1,000 members.

- Material on bomb-making and other violent activity is continuing to circulate across boogaloo groups on Facebook. The content includes a Google Drive folder that contains dozens of instruction manuals for bomb making, kidnapping, and murder.

- Despite Facebook’s promise to stop recommending boogaloo groups to users, the company’s algorithms continue to suggest boogaloo-related groups and pages, even when they don’t use the word “boogaloo” in their names.

- Facebook has sought to justify its selective approach to removing boogaloo groups by arguing that some parts of the movement are not violent—even though the term “boogaloo” is synonymous with civil war.

Evolving Tactics

Facebook’s slow and sometimes piecemeal approach to removing boogaloo content has given boogaloo group administrators ample time to adjust their online strategies.

Following TTP’s first boogaloo report in April, a number of private Facebook groups began changing their names to replace the word “boogaloo” and known derivations like “big igloo,” “boojahideen,” and “big luau,” with other terms like “[redacted]” and “liberty” in an effort to avoid notice by Facebook.

The simple rebranding worked, allowing many of the boogaloo groups to avoid detection by Facebook and continue operating—some of them to this day.

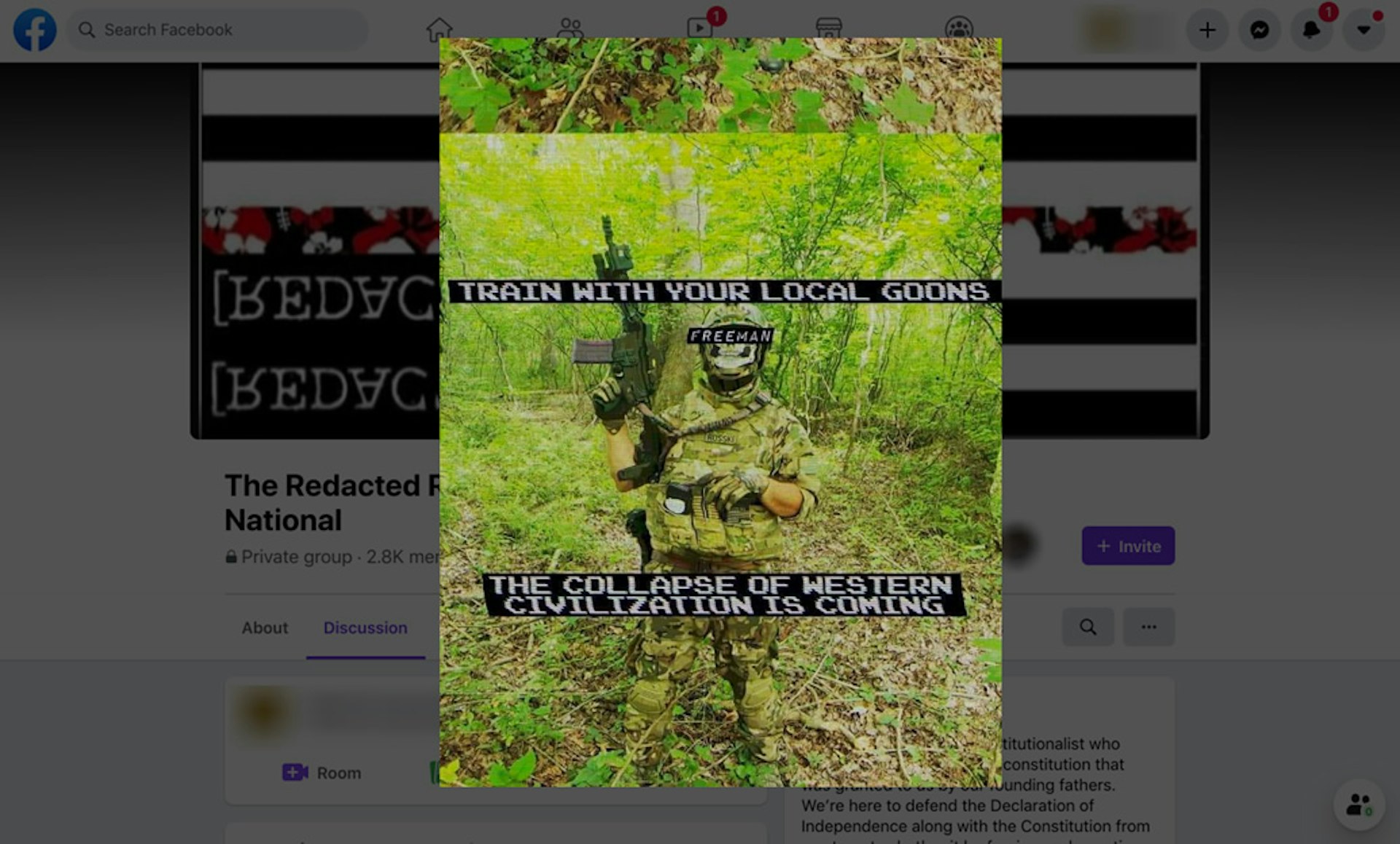

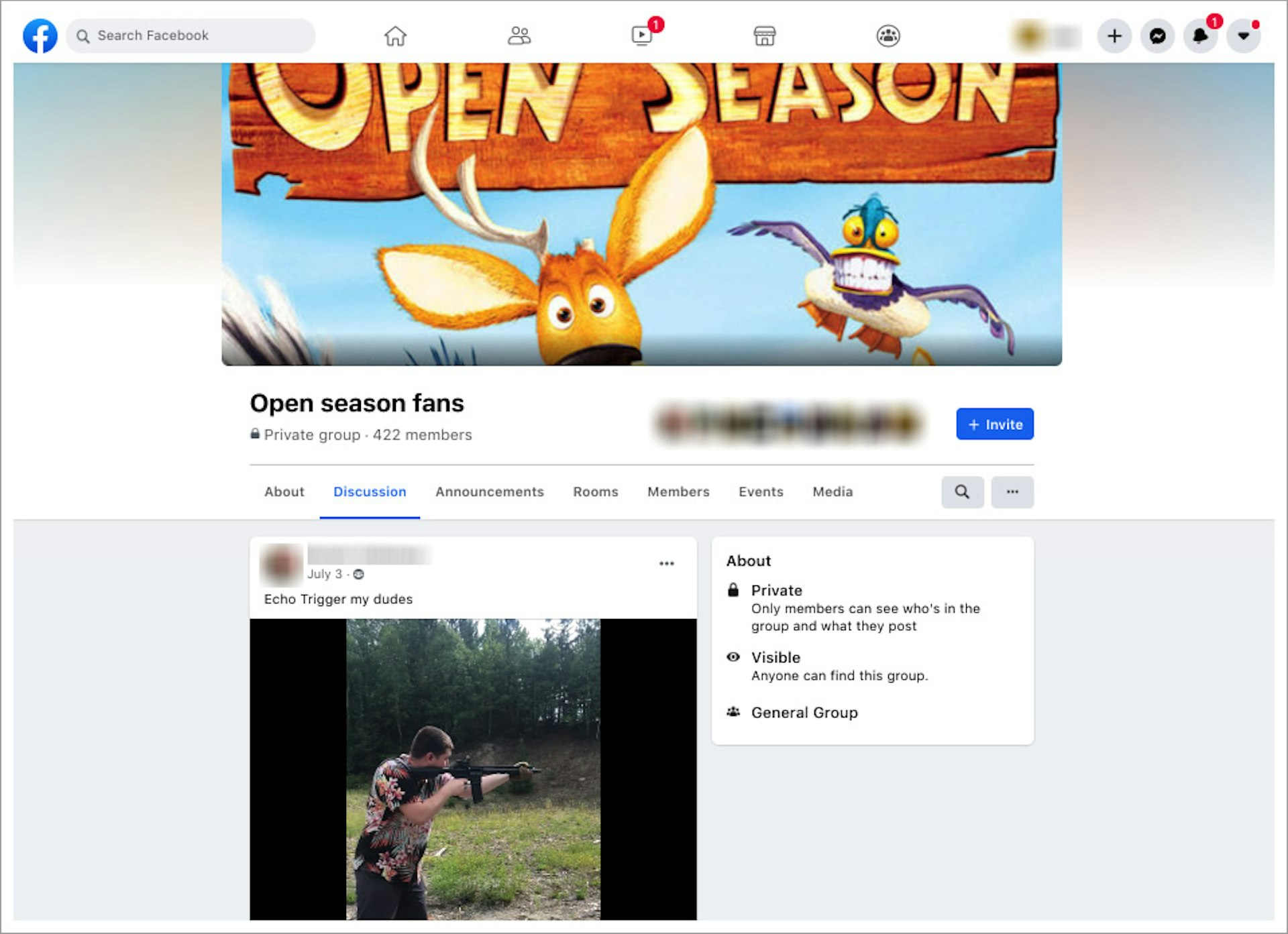

Boogaloo admins have also created new groups with harmless-sounding names related to things like children’s movies. One example is a group called “Open Season Fans,” which was created on June 5 and features an image of the 2006 animated movie about a bear and a deer trying to avoid hunters. (The name of one of the film’s main characters is Boog—a word that has also been used as a shorthand for “boogaloo.”)

Like other boogaloo groups, Open Season Fans is private, but upon joining it, it’s clear from the content that it is used for boogaloo organizing. Its members share propaganda—like photos of armed boogaloo supporters joining protests for Black Lives Matter. The group’s first post links to an article about the use of boogaloo code words to thwart Facebook’s automated systems.

Groups like Open Season Fans have continued to point supporters to other boogaloo groups, allowing the movement to expand its presence on the social network. TTP identified a total of 110 new boogaloo groups that have been created since June 30, the day Facebook announced it was banning a “violent” boogaloo network; 18 of those groups were created the same day as Facebook’s announcement.

Meanwhile, TTP found that 39 of the 125 boogaloo groups it identified in its initial April report are still active on Facebook. Many of the remaining groups are state chapters. Some, like “Prestige Worldwide” and “defending the 2nd,” changed their names to obscure their boogaloo affiliation, while others, like “Nashville Boogaloo Boys,” did nothing to hide the label.

In total, TTP identified nearly 150 boogaloo groups on Facebook that were active as of July 24. That’s roughly 20% more than TTP had identified in April.

Co-opting the Media

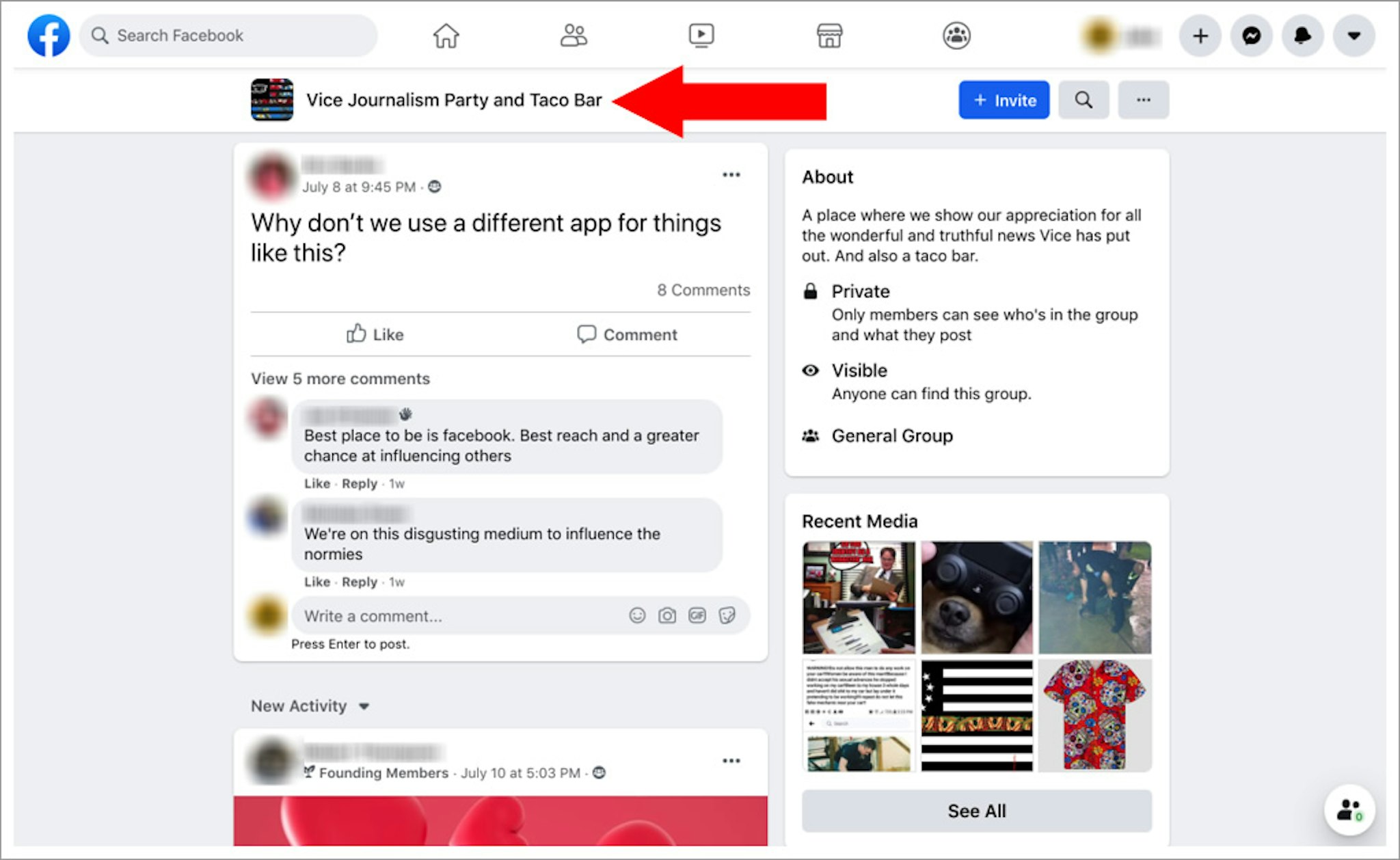

Another recent strategy adopted by the boogaloo movement on Facebook involves mimicking the names of media outlets.

Boogaloo-oriented groups have been incorporating the names and logos of news organizations like CNN, VICE, MSNBC, and Fox, often in mocking tones. “CNN Salsa and Sombrero Enthusiasts,” “MSNB-sí Bois,” “FoxNews Fajita Emporium and Spa,” and “Vice Journalism Party and Taco Bar” are among the new groups identified by TTP.

Two of these groups have amassed more than 1,300 members, while some others are approaching the thousand-member mark. They operate in the same way as the older boogaloo groups—sharing propaganda, recruiting new members, and raising money through the sale of boogaloo merchandise and dissemination of GoFundMe campaigns.

The admins of these groups often tell members not to use words like “boogaloo,” “boog,” or “big igloo,” or even the more recent replacement code words like “redacted,” in order to evade Facebook’s automated systems.

The Anti-Defamation League (ADL), a leading anti-hate organization, has also written about the boogaloo movement’s adoption of media names on Facebook. After ADL’s article on the subject appeared online, boogaloo supporters created new Facebook groups mockingly named after ADL itself.

Another new boogaloo group—“Mark Zuckerberg Fan Club”—took the name of Facebook’s CEO.

Molotov Cocktails and Gasoline Bombs

After Facebook told HuffPost it was reviewing the content highlighted in TTP’s April report, the company took months to remove some of the most dangerous material.

For example, instructions for making gasoline bombs and Molotov cocktails, which were posted in a group flagged by TTP, remained accessible until early June. Facebook only removed the material on June 8, the day after TTP tweeted screenshots of the still-active post, tagging Brian Fishman, Facebook’s director of counterterrorism and dangerous organizations.

Likewise, a number of documents on military tactics, including a 133-page manifesto titled Yeetalonians, remained available in the Files section of multiple boogaloo groups for months after TTP identified them in April. Yeetalonians offered advice on weapons, propaganda and psychological warfare strategy for boogaloo supporters. The manifesto was finally deleted on June 30 when Facebook removed the groups in question.

Still today, dangerous content continues to circulate in Facebook boogaloo groups monitored by TTP.

A Google Drive folder called “For Duncan Lemp” was shared across a number of groups on July 19 and includes manuals for bomb making, terrorist kidnapping, evading authorities, and different methods of murder. Duncan Lemp is the name of a Maryland man who was killed in a police raid on his home and has become a martyr for many in the boogaloo movement.

Real-world Violence

TTP was first to report in April that a man named Aaron Swenson, who was arrested by Texas police after livestreaming himself on Facebook looking for an officer to kill, had “liked” more than a dozen Pages that mentioned boogaloo in their names. It was an early indication of an online boogaloo supporter engaging in real-world attempts at violence—and it was not the last.

Over the next few months, authorities arrested other boogaloo supporters on various violence-based charges, making national headlines. A common thread among all the suspects: They were members of private boogaloo groups on Facebook, which often featured talk of tactics and weapons.

In early June, the FBI Joint Terrorism Task Force outlined a case against three self-identified members of the boogaloo movement, alleging they planned to target a Black Lives Matter protest in Las Vegas with Molotov cocktails.

All three were members of private boogaloo groups flagged by TTP in April that Facebook had allowed to remain active. One of the groups—known as [Redacted]bastards: Intelligence and Surveillance, which had changed its name following TTP’s report to remove an overt reference to the boogaloo—included the instructions for making Molotov cocktails and gasoline bombs.

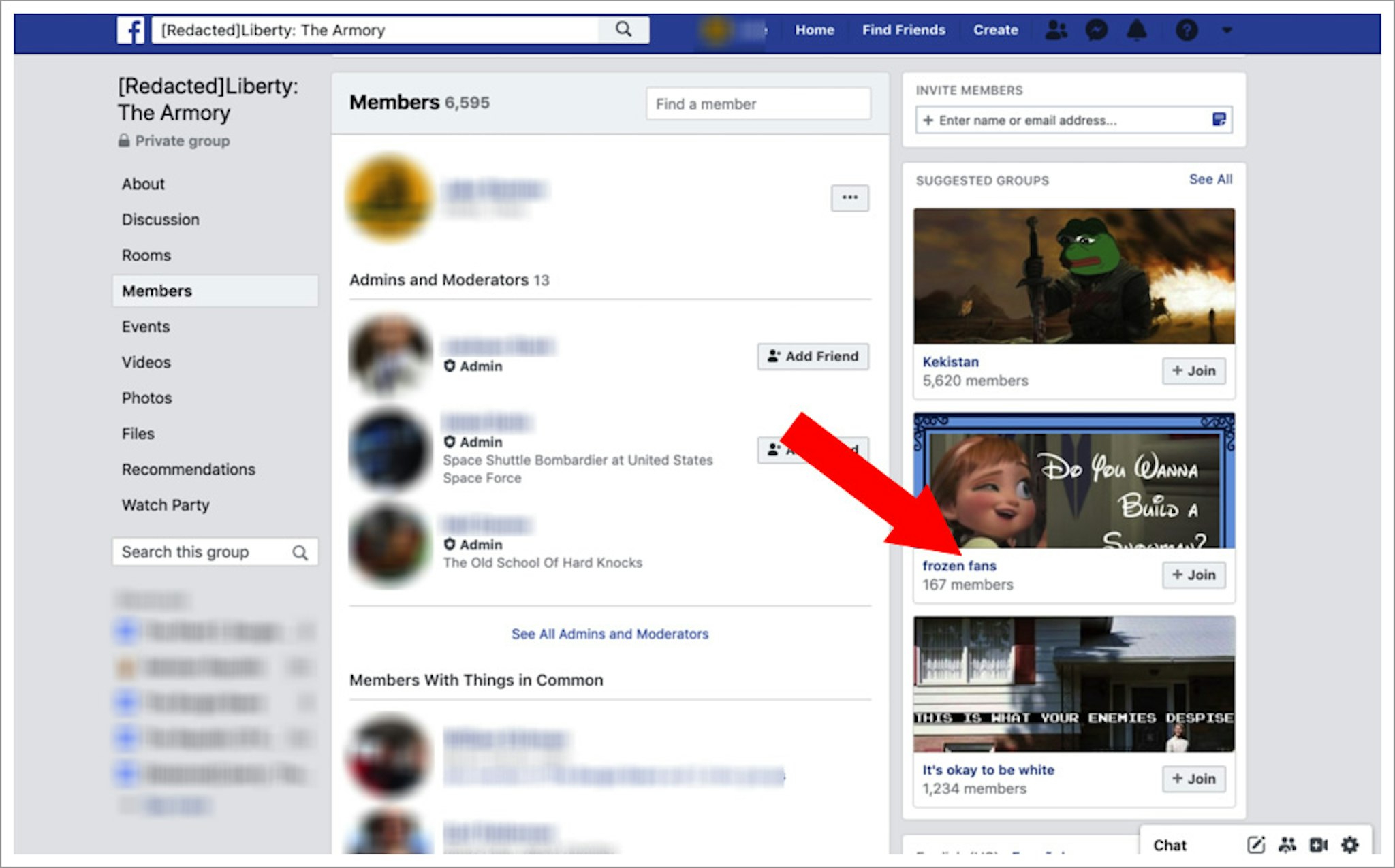

Around the same time, a boogaloo supporter in Oakland, California, named Steven Carrillo was charged with murder and attempted murder of law enforcement officers. According to the federal complaint, Carrillo and an accomplice exchanged messages in a Facebook group, discussing their plan to attack authorities. Carrillo was a member of a group called “BoojieBastards: The Armory” (later “[Redacted]Liberty: The Armory”), which TTP named in its April report. Facebook didn’t take down the Armory group until June 17, following coverage of Carrillo’s alleged murder spree.

Facebook later told CNET that it would “remove content that supports these attacks.” But TTP found conversations in multiple private boogaloo groups in which members praised Carrillo with comments like, “This man is my hero,” and “Kill em all.” Those posts stayed up for about two weeks, until Facebook deleted the groups in question on June 30.

Boogaloo Recommendations

Months after Facebook’s boogaloo problem came to light, the company continues to recommend boogaloo content to users through its “related pages” and “suggested groups” functions, effectively amplifying the reach of the movement.

The trend has continued even after Facebook told Reuters in early June it would no longer suggest groups associated with the boogaloo.

Take “frozen fans”—a new Facebook boogaloo group that, like “Open Season Fans,” uses the name of a children’s movie. TTP observed that Facebook repeatedly recommended “frozen fans” alongside boogaloo groups and content through its “suggested groups” feature. It appeared in recommendations as recently as July 10.

Such findings track with a June 18 report by Judd Legum in Popular Information. Legum’s research found that Facebook’s “related pages” algorithm was still promoting boogaloo pages, including those with large followings like the Rhett E. Boogie page previously flagged by TTP.

TTP identified many of the 110 new boogaloo groups listed in this report using Facebook’s own recommendation systems.

Tortured Logic

In formulating policy around the boogaloo, Facebook has attempted to make a distinction between non-violent and violent members of a movement that is geared toward a militant uprising against the government.

The term “boogaloo” emerged out of a series of memes and jokes shared by militia enthusiasts on social media about the cult classic “Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo.” As the memes evolved into a movement, the movie reference was eventually shortened to “boogaloo” as a synonymous term for an uprising .

Facebook’s June 30, 2020 announcement banning a “violent US-based anti-government network” argued that the network “uses the term boogaloo but is distinct from the broader and loosely-affiliated boogaloo movement because it actively seeks to commit violence.”

While acknowledging that the boogaloo name has been “adopted by a range of anti-government activists who generally believe civil conflict in the US is inevitable,” Facebook sought to make distinctions between different kinds of boogaloo “activists,” saying they are divided over issues like “the goal of a civil conflict, racism and anti-Semitism, and whether to instigate violent conflict or be prepared to react when it occurs.”

But the statement—which came the same day that a trio of Democratic senators demanded that Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg take action against white supremacists and other extremists on the platform—failed to grapple with the fact that the very concept of boogaloo is predicated on violence.

Facebook’s hedging on the issue has drawn warnings from experts like Joan Donovan, director of the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy at Harvard Kennedy School. She called it a dangerous “fallacy” that would allow boogaloo supporters to “continue to operate so long as they tone down their violent rhetoric.”

Even with Facebook’s focus on “violent” boogaloo supporters, the company should arguably have acted sooner, given that much of the content in question, such as bomb making and praise for terroristic murder, violates Facebook’s long-established Community Standards.

The modern boogaloo movement was born online and relies on the reach of social media to fuel its growth. Facebook’s approach to the problem—removing select groups and individuals on the platform—has led boogaloo supporters to simply shift their tactics.

Many of those supporters are doing the same organizing and intel-sharing on Facebook under new names, slipping easily past Facebook’s supposed crackdown.