Click here to see how TTP identified and tracked Google’s planes

A dozen years ago, Google executives Larry Page, Sergey Brin, and Eric Schmidt bought a fighter jet—an unusual purchase, even for tech billionaires who maintain their own fleet of aircraft.

The trio needed the two-seater Alpha Jet to fulfill their end of a sweetheart deal they brokered with NASA giving them coveted access to Moffett Field, a federal airfield less than 4 miles from Google’s Mountain View, California, headquarters.

But Google’s leadership often failed to fulfill its end of the bargain. The Alpha Jet, which was meant to collect atmospheric data for NASA, wasn’t available in the early years of the arrangement, and it has been out of action since a little-noticed crash in 2018. But the tech giant didn’t lose its privileged access to the airfield.

In fact, Google has made heavy use of Moffett over the years, with company executives taking thousands of flights to and from the airfield, according to a Tech Transparency Project (TTP) analysis of FAA flight data. The story of how Google kept this arrangement going for more than a decade—despite accusations of special treatment—shows how the search giant has used its influence with government officials to preserve a cherished corporate perk.

Google’s fighter jet crash landed in 2018 in Sacramento during an instructional flight. Credit: KCRA News.

Google executives’ use of Moffett, which is not available to other companies, has given them a highly convenient airfield next door, sparing them the 12-mile trip along Silicon Valley’s traffic-clogged roads to the airport in San Jose, or a longer ride to the San Francisco airport.

While the acquisition of the fighter jet and Google’s initial deal for Moffett Field have been reported, several key new details have not, including the crash, the extent of Google’s use of the airfield, and an array of efforts by Google and its allies to maintain the company’s exclusive access.

There have been problems with Google’s deal at Moffett from the start. For example, NASA did not advertise that the hangar was available before it leased space to the Google executives, giving the company uncontested use of the airfield.

At times, Google has appeared to get more out of the deal than the government. Before the fighter jet purchased by Brin, Page and Schmidt was ready to start collecting atmospheric data for NASA, Google executives had already turned Moffett into their corporate airport, flying into or out of the airfield nearly 600 times, according to FAA records.

As the executives’ use of the airfield became increasingly controversial, NASA initially appears to have rejected their efforts to extend the deal beyond 2014. The space agency even explored the possibility of handing off Moffett Field to another government agency or a municipality. But members of the community and powerful Google allies in Congress intervened to lobby against such a move. In the end, NASA awarded a 60-year lease to a Google affiliate over a competing bid from a development firm that sought to open up the facility to more flights and outside tenants.

The crash of the fighter jet in 2018 disrupted the data collection for NASA, but as recently as March 2020, the Google executives still had a live agreement that required them to collect data.

“There’s so many people chomping at the bit to land at NASA,” the mayor of Mountain View said the first time a Boeing 767 owned by Page and Brin was spotted on the runway at Moffett Field in 2007. “I think it’s good when we all play by the same rules.”

A Questionable Arrangement

The sweetheart deal at Moffett Field was struck between H211 LLC, a company controlled by Page, Brin, and Schmidt, and NASA in July 2007. In exchange for the collection of atmospheric data and an annual payment of $1.4 million, the Google executives were permitted to park up to nine of their private aircraft at the federal airfield, part of NASA’s Ames Research Center.

An amendment to the initial deal, signed the following month, loosened the terms of the arrangement by allowing Google to assist space science and astrobiology missions to meet its obligations. And the next day Google executives provided the space agency with two Gulfstream jets that scientists used to collect data about the Aurigid meteor shower.

NASA didn’t always get what it asked for, though. In July 2008, NASA hoped to use a Google jet to collect data from the reentry of a European spacecraft. But the Google executives had other plans: The plane was used to shuttle guests to then-San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom’s ritzy wedding in Montana. (The bride rode to the wedding site on a black stallion, sidesaddle.) Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin and their spouses appear to have been at the party, as was Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi. Willie Brown, another former mayor of the city, said he flew in from California aboard Google’s 757, “and it was like flying in seven connected living rooms.”

In all, FAA records show that a total of three Google planes—the Boeing jet and two Gulfstreams—made trips to Montana that weekend, with the Boeing flying in and out of Moffett Field.

Google’s arrangement at Moffett quickly drew scrutiny. Just six weeks after the July 2007 deal took effect, the director of the Ames Research Center acknowledged in an internal memo that “Not everyone can nor should use this airfield.”

“NASA has specific criteria to determine who can partner with us and whether they may use their aircraft at Moffett,” the director wrote. “All requests by a private entity undergo a rigorous review process and every request must demonstrate a relationship to NASA missions.”

A few years later, a NASA watchdog found problems with the process used for the Google deal, and with a separate agreement between a Google subsidiary and the space agency. An August 2012 audit by NASA’s Office of the Inspector General (OIG) found that NASA had never advertised that hangar space was available, and that H211 only knew about it because of its dealings with the agency on other matters. The OIG recommended that NASA widely publicize all future leasing opportunities and, as a result, NASA agreed to change its policies.

The August 2012 report also found that NASA had granted a 2008 lease at Ames Research Center to Planetary Ventures, a company owned by Google, without advertising nationally, and that Ames officials were not able to point to any analysis or methodology they used to determine whether Planetary Ventures “met the Center’s overall goals for use of the land and provided the best value to NASA.”

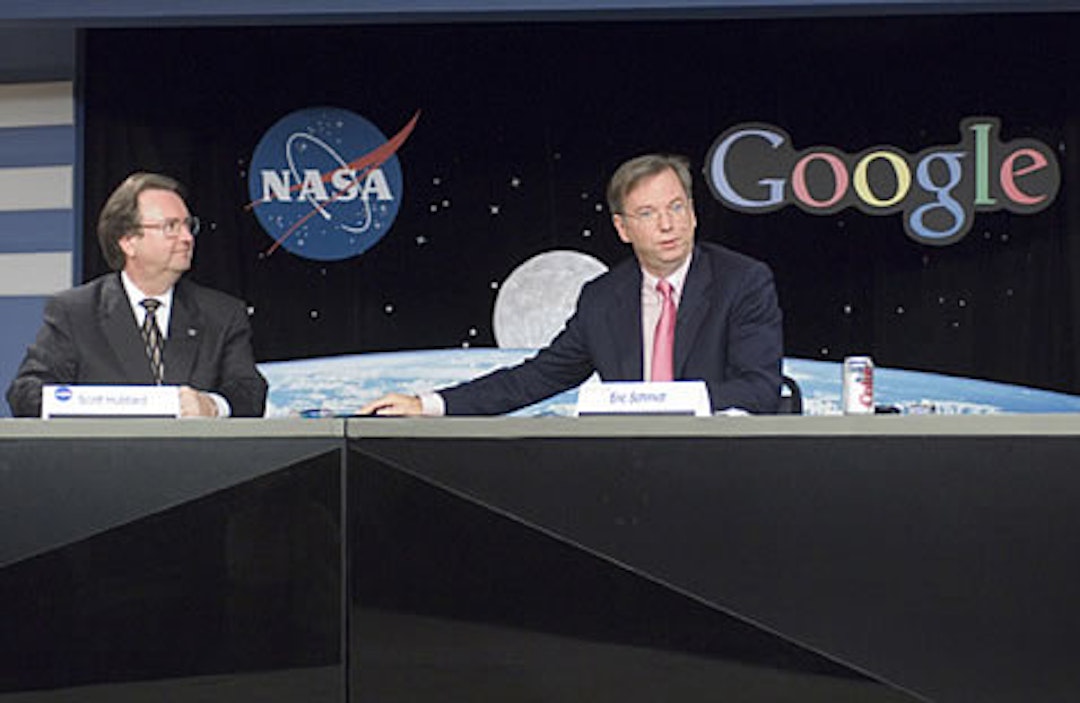

Then-Google CEO Eric Schmidt, right, with Scott Hubbard, director of the NASA Ames Research Center, at a 2005 event. Credit: Dom Hart.

A key part of NASA’s justification for the deal with H211 was the company’s pledge to allow the agency to outfit aircraft in its fleet with scientific equipment that would be used to collect atmospheric data. The proposal was modeled on similar programs in Europe, where such equipment was installed on commercial planes. But there is no indication that NASA had any need, or intention, to launch its own program—until Google’s unsolicited request for a lease.

Just months after the agreement was signed, NASA realized that it could not make the necessary modifications to H211’s fleet of Boeing and Gulfstream planes without obtaining new Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) certifications for each change, a time-consuming and expensive process that would have significantly reduced the value of the planes to NASA. That’s when Google’s flight team turned to the Alpha Jet.

A New Plan Takes Off

To meet its obligation, H211 purchased the former German Air Force Alpha Jet—which was jointly manufactured in 1982 by Dassault-Breguet and Dornier—in December 2007. The FAA designated it as an experimental aircraft, meaning that it was not subject to the same modification regulations as commercial planes. The fighter jet was registered under the tail number N165XA until September 2009, when it began using the tail number N2165.

The FAA issued H211 an experimental airworthiness certificate for the plane on July 6, 2010, and by January 2011 the jet had begun collecting data for NASA. By that point, passenger jets owned by Google executives had already flown into or out of Moffett Field at least 576 times, according to FAA flight records, though there is no evidence that Google had provided any sustained data collection efforts for NASA in return.

An Alpha Jet can reach a top speed of 633 miles per hour, and its agility allows it to easily perform steep spiral maneuvers needed to fly around large plumes of smoke and other conditions. Typically, the jet flies its NASA missions at altitudes up to 27,000 feet and it sometimes flies as low as just 1,000 feet from the ground. Most of the Alpha Jet’s NASA missions have taken place over California and Nevada, as the plane has a range of less than 700 miles and can only spend two-and-a half hours in the air at a time.

The Google Alpha Jet ahead of a flight to check air samples from California wildfires, 2015. Credits: NASA Ames, Warren Gore.

The number of flights made by the jet to measure air samples for NASA has varied slightly over the years, but has consistently been low. (Most information about the jet’s flights was found in NASA reports, rather than FAA flight records, which appear to be incomplete for this aircraft.) Google’s Alpha Jet collected data during 59 flights between August 2012 and July 2013, an average of nearly five flights a month. An agency report issued in 2014 said the jet averaged between three and four missions a month.

By contrast, Google's passenger planes departed from Moffett Field at least 181 times between August 2012 and July 2013, a rate that is more than triple the number of Alpha Jet flights during that period.

Though NASA’s OIG concluded in December 2013 that H211 had provided a benefit to NASA—which was “a requirement for the type of lease Ames entered into with H211”—this opinion does not appear to have been fully shared by NASA officials.

“If you try to justify the lease with the Alpha Jet, it doesn't work,” John Yembrick, then the director of strategic communications at Ames Research Center, wrote in a May 2012 email that lamented a local television station’s critical coverage of H211’s relationship with NASA.

A Crash Landing

NASA’s use of the Alpha Jet for atmospheric research came to a screeching halt on June 14, 2018, when the plane crash-landed at Mather Airport in Sacramento. H211 and another company owned by Google executives called Blue City Holdings were using the jet for an instructional flight, and while practicing a landing without the use of the plane’s flaps, both the pilot and instructor failed to notice that they had never lowered the plane’s landing gear. The instructor and trainee survived the incident, though the jet caught fire upon hitting the ground and the impact caused substantial damage to the belly of the plane.

NASA acknowledged in May 2019 that the program it created for the Alpha Jet had faced “a year of aircraft down-time,” which suggests that it was unable to collect needed data during that period. NASA also said it had gained access to a new Alpha Jet—whose ownership is unclear—that it hoped to begin flying by the fall of 2019. But it has not posted any updates on its website or on social media since then, which appears to indicate that the new plane is still grounded.

Even after the Alpha Jet program was up and running, NASA’s inspector general acknowledged another problem that “engendered a sense of unfairness and a perception of favoritism toward H211 and its owners.” In a December 2013 report, the IG noted that H211 had mistakenly paid between $3.3 million and $5.3 million below market rate for fuel at Moffett Field between September 2007 and August 2013, due to a “misunderstanding between Ames” and the fuel provider. H211 had been charged a discounted fuel rate intended only for government agencies and contractors, not just for its NASA flights, but also for its private flights.

As a result of the fuel error, NASA’s OIG recommended that “NASA explore with the company possible options to remedy this situation.” H211 said in December 2013 that it would review the OIG’s report, but it is unclear if the Google executives ever paid any reimbursements for the lower fuel costs after becoming aware of the findings.

Help from Influential Allies

In the midst of the allegations about NASA’s favoritism toward H211, the agency determined that it no longer had a need for Moffett Field, putting the Google executives’ access to the airfield in jeopardy. Google subsequently leaned on its cozy relationships in Congress and at the White House to fight off NASA’s effort to rid itself of an unnecessary airfield that was becoming a public relations problem.

NASA eventually gave in to the political pressure. Instead of handing the airfield off to another government entity, the agency signed a new long-term lease with a Google affiliate in November 2014, allowing the Google executives to maintain access to an airfield that has become a key part of the company’s expanding Bay Area footprint. Google also gained access to three large hangars originally built to house blimps. The oldest one, which was constructed in 1933 and is known as Hangar One, was found to contain dangerous levels of toxic chemicals, lead, and asbestos. The side paneling of Hangar One was subsequently stripped off of the building in 2011.

When H211 offered to restore Hanger One in exchange for use of it once the company’s existing lease expired, Reps. Anna Eshoo (D-CA) and Zoe Lofgren (D-CA) wrote a March 2012 letter urging NASA to accept a long-term lease on the property. NASA said that it would instead explore transferring Hangar One and the rest of the Moffett Field to the General Services Administration (GSA), which would then determine whether to give the airfield to another federal agency or to make it available for some other public use.

Image of Hangar One at Moffett Field, Calif., taken in 1999. Credit: NASA Ames Research Center.

Eshoo—whose district includes Moffett Field and Google’s Mountain View headquarters—and Lofgren, whose district is next door, responded by criticizing the agency and its plans. The lawmakers also continued to push NASA to accept H211’s rental offer, citing the money that the government had already spent on stripping down Hangar One, among other things.

Eshoo lobbied the White House to block the transfer of the property and even appears to have hand delivered a letter in support of H211’s lease proposal to President Barack Obama in May 2012. The letter was authored by the Silicon Valley Leadership Group, which includes Google as a member.

Though NASA ultimately refused to sign a new lease with H211, Eshoo’s intervention resulted in NASA maintaining possession of the airfield. On March 1, 2013—three days after a meeting at the Capitol between Eshoo, NASA, GSA, and White House officials—the parties announced that Moffett Field would remain in NASA’s possession and that the airfield would be available for lease. The leasing announcement said that NASA was focused on expediting the re-siding of Hangar One.

Google affiliate Planetary Ventures placed a bid on the lease, as did Bay Area contracting firm Orton Development. Both companies proposed using the Moffett Field hangars for scientific purposes. But while Google sought to use the space to conduct its own corporate research, Orton said it would seek multiple tenants, including universities and NGOs. Orton also proposed increasing the number of flights out of the airport to serve “both public and private users,” while Google said it would maintain the status quo of limited private and government flights out of Moffett Field.

The GSA and NASA chose to move forward with Google’s bid in February 2014. In November 2014, after the lease was finalized, Eshoo issued a press release calling the contract a “long-awaited victory…after a highly competitive process.”

The award allowed Google’s executives to maintain access to runways that their planes had landed or taken off from 1,890 times since 2007. Google’s leadership had also relied on Moffett Field as a home base for their helicopter travel within the Bay Area, as Bell helicopters linked to H211 re-fueled at Moffett Field at least 31 times between August 2009 and March 2013. Since signing the new lease, planes belonging to Google’s leadership have flown in or out of Moffett Field at least 2,077 times, according to TTP’s review.

According to Google’s 2013 lease proposal, the company anticipated that it would “Re-side Hangar One within two years of receiving necessary permits and approvals.” The company has yet to start that process, and it does not expect to begin residing the hangar until the site undergoes a cleanup process that could take until 2023.

In the meantime, Google has used another hangar at Moffett Field to house Project Loon, an effort to use hot air balloons to bring internet service to remote areas. The company has also leased hangar space to a company called LTA Research & Exploration, a Sergey Brin vanity project that appears to be attempting to build a giant blimp that has been described as both an “air yacht” and a potential vehicle for humanitarian missions.

All that activity comes amid a broader push by Google to invest in the area surrounding Moffett Field. Google has spent more than $1 billion in recent years to acquire nearby real estate for what will eventually be more than 1 million square feet of office space. The company is also in the process of constructing more than 600,000 square feet of office space on the Moffett Field grounds that it originally began leasing from NASA in 2008.

These investments in the area help explain why Google is willing to spend as much as it has to maintain its access to Moffett Field’s runways for private flights. Google has paid NASA between $10.25 million and $15.5 million annually during the early phase of its 60-year lease of Moffett Field. But while the amount Google is paying the government has gone up, the Google executives still appear to be getting a sweetheart deal. According to SEC filings , they have only reimbursed the company less than $2 million to park their planes there—essentially the same rate that H211 was paying during its prior lease. LTA Research & Exploration has also paid Google between roughly $101,000 and $2.3 million in annual rent since 2016. Google has effectively spent up to $13 million annually to preserve its founders’ flight perks, while it remains years away from re-siding Hangar One, which was supposed to be the “primary objective” of the lease.