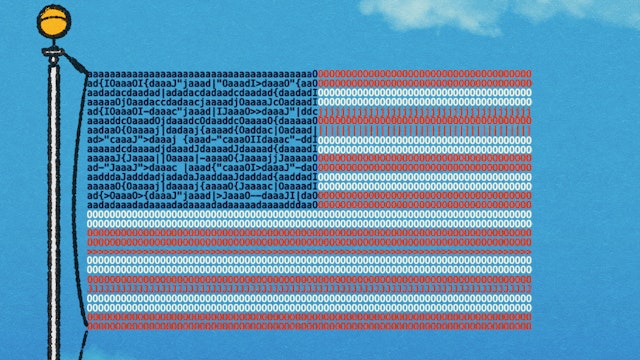

Google is deploying its well-developed influence machine in Washington to amplify its legal arguments and rally public opinion ahead of a Supreme Court case that could radically curtail its business model, the Tech Transparency Project (TTP) has found.

The search giant has spent years building up a network of public policy groups, academics, and foundations that the company uses to amplify its positions in legislative and regulatory debates in Washington. Now, Google is activating that network to push its arguments in a critical Supreme Court case that has the potential to reduce the legal protections enjoyed by Google and other Big Tech companies.

A TTP review found that 44 parties that signed amicus briefs in support of Google’s position in the Supreme Court case are funded by or linked to Google. Many are stalwarts of Google’s influence operation, including the Chamber of Progress, the Computer & Communications Industry Association, and advocacy group Engine. Others appear to be new to the mix, including a slew of YouTube content creators with large followings.

Organizations funded by the Koch network are also heavily represented in the amicus briefs that support Google’s position, including the Americans for Prosperity Foundation, the Pelican Institute for Public Policy, and the Independence Institute. As TTP has previously reported, Google for years has cultivated an alliance of convenience with the conservative network established by billionaire industrialists Charles and David Koch to push back against regulation.

Google’s influence efforts reflect the high stakes for the company as the Supreme Court prepares to hear oral arguments in Gonzalez v. Google on Feb. 21. The case focuses on Section 230, a more than two-decade-old law that shields Google and other tech platforms from liability over user-generated content. The family of Nohemi Gonzalez, an American woman killed in an ISIS attack in Paris in 2015, claims in a lawsuit that Google-owned YouTube aided ISIS recruitment by recommending ISIS videos to users in violation of U.S. anti-terrorism law. The family argues that YouTube’s recommendations are not protected by Section 230.

Google, like other big tech companies, is alarmed at the possibility that the Supreme Court could restrict or remove legal protections for algorithmic recommendations, which are a central feature of YouTube and other social media platforms. The company’s general counsel warned last month that changing Section 230 could “impede access to information, limit free expression, hurt the economy, and leave consumers more vulnerable to harmful online content,” adding that a “broad cross-section of experts, academics, organizations and businesses from across America also recognize the importance of” the law. What Google failed to note, however, is that it provides financial support to many of the experts and groups promoting that view.

Army of Paid Allies

Many of Google’s reliable proxies have jumped into the Gonzalez case to support the company’s position on 230. Among those filing amicus briefs backing Google are the Chamber of Progress, a tech industry coalition that is backed by Google and run by a former Google policy executive; the Google-funded Computer & Communications Industry Association (CCIA); Engine, a non-profit that claims to be a voice for tech startups but appears to be little more than a front for Google; and Joshua Wright, a former FTC commissioner and George Mason University law professor with longstanding ties to Google.

“Eliminating any portion of those protections would dramatically alter the Internet for the hundreds of millions of Americans, and billions of worldwide users, who depend on online services for information, education, entertainment, and income,” the Chamber of Progress wrote in its brief, closely echoing Google’s arguments.

Outside the legal arena, these Google-linked groups have also sought to build public support for the company’s position. For example, CCIA tweeted last month that altering or abolishing Section 230 would cause consumers to experience “either a deluge of harmful content or over-sanitized versions of their favorite platforms,” while the Center for Democracy and Technology (CDT) said the Supreme Court should uphold interpretations of Section 230 that protect “online free expression.” Meanwhile, the Chamber of Progress sought to tie Section 230 to the issue of abortion rights, writing in a public letter to Attorney General Merrick Garland that without the provision, “online services might be compelled to limit access to reproductive resources, for fear of violating various state anti-abortion laws.”

Many of these organizations are veterans of prior regulatory battles involving Google. For example, the Copia Institute, Engine, and TechFreedom were among the Google-funded groups that led the charge against an anti-sex trafficking bill opposed by Google. The measure, which created a carveout in Section 230 protections for sex trafficking content, eventually passed and was signed into law in 2018.

The Authors Alliance, which filed a brief backing Google in the Gonzalez case, also has a history of jumping to Google’s defense. Months after its launch in 2014, the alliance—co-founded by Berkeley law professor Pamela Samuelson—took Google’s side in a copyright lawsuit over its book-scanning project, saying the book database gives “authors new hope that their books will find readers.” (Samuelson, who is today on the board of the Authors Alliance, heads the Berkeley Center for Law & Technology, which received $500,000 from Google in 2011 as part of a cy pres legal settlement over privacy violations related to the Google Buzz social network—and later got funding directly from Google.)

During the last Congress, the Authors Alliance and Google-funded groups that have sided with the company in the Supreme Court case, including the Chamber of Progress, CDT, and Public Knowledge, raised concerns about the Journalism Competition and Preservation Act, a bipartisan bill that would allow news organizations to band together to negotiate compensation from internet platforms. That position was very much in line with Google, which mounted a lobbying blitz against the measure. (The bill ultimately failed to advance.)

Recruiting YouTubers

With the Gonzalez case, Google appears to be adding new voices to its influence operation. A collection of 17 social media content creators and influencers, most of them YouTubers, joined the Authors Alliance brief backing Google’s position. (A footnote in the brief states that Google-backed Engine funded the preparation and submission of the document.) The content creators range from an English language teacher to a man who posts videos with his family like “Giant Turtle Attacked my Dad!”

One of the amicus signatories is Jordan Maron, who runs the YouTube channel CaptainSparklez. In January, he posted a video for his 11.4 million subscribers that was markedly different from his usual fare of Minecraft videos. He launched into a long, wonky explanation of Section 230 and the Gonzalez case, warning that the loss of algorithmic recommendations could cause content creators to suffer a “massive loss of jobs.” He also made clear that YouTube had recruited him to sign the brief:

I was even invited to a group call with YouTube employees, other creators, creator-adjacent businesspeople, to inform us of what this is, and ask if we wanted to be part of something called an amicus brief, which will actually be used during arguments in the trial.

Maron, like other content creators who signed the brief, appears to have a transactional relationship with Google. In a previous video on his channel, he unboxed a wireless router, Android phone, and other products sent to him by Google, and thanked the company for sponsoring the video.

Another YouTuber on the brief, Milad Mirg, who mostly posts videos about his job at Subway making sandwiches, once filmed himself wearing a giant camera contraption in New York City’s Times Square to “celebrate the 15th birthday of Street View,” the Google Maps feature. He said Google lent him the device. Two other YouTube personalities who signed the brief, therapist Kati Morton and Dr. Mikhail Varshavski, have published videos that are sponsored by Google.

Leveraging the Koch network

A dozen organizations linked to the conservative Koch network also signed amicus briefs supporting Google’s position in the Gonzalez case. These include the Americans for Prosperity Foundation; the Pelican Institute for Public Policy, the James Madison Institute, and the Independence Institute.

This is part of a pattern for Google. As TTP reported in 2019, the Koch family’s dark-money juggernaut has become one of Google’s strongest backers in Washington as the company contends with the backlash against Big Tech—and Google, once a beacon of progressivism, has embraced the Kochs and many of their conservative causes.

“Nothing has fostered the growth of the internet like automated recommendation systems, which help users find what they want in oceans of information,” the Koch-linked groups wrote in their brief, arguing these systems should be protected from liability.

In a sign of how much Google’s interests have converged with the Koch network in Washington, many of the groups siding with Google in the Supreme Court case are funded both by the company and Koch money.

The list includes the Washington Legal Foundation, the R Street Institute, and the Center for Growth and Opportunity at Utah State University, which was launched with a $25 million gift from Charles Koch.1 Another group, the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation, is funded by Google and the Charles Koch Institute.

Another example is Geoffrey Manne, who signed onto a pro-Google brief in the Gonzalez case. He is president and founder of the International Center for Law & Economics, which has also gotten donations from Google and the Charles Koch Foundation. (As TTP has reported previously, Manne has written numerous policy papers over the years that support Google’s positions on antitrust, search neutrality and copyright/patent issues.)

The Center for Growth and Opportunity has been active in promoting Google-friendly policy positions, like opposing the above-mentioned Journalism Competition and Preservation Act. The group also came to Google’s defense in 2021 by cautioning Merrick Garland to think twice before pursuing the Justice Department’s antitrust lawsuit against Google.

Interlocking ties

TTP found other connections among Google’s allies on the Gonzalez case. Take Eric Goldman, a law professor at Santa Clara University. Goldman—a faculty member at the university’s Markkula Center for Applied Ethics, which received funding from Google as part of the cy pres legal settlement involving Google Buzz—filed an amicus brief in support of the company at the Supreme Court. (He previously took a position consistent with Google’s view during the debate over the sex-trafficking bill in Congress.)

Goldman is a co-founder of the Trust & Safety Foundation, which also filed a brief supporting Google in the Gonzalez case, arguing that limiting Section 230’s protections for recommendation and content moderation algorithms “could be extremely burdensome to T&S teams and lead to even more content removal.” The foundation’s “sibling organization,” the Trust & Safety Professional Association, counts Google as one of its “founding supporters.”

Google has enjoyed a wave of support for its legal arguments in the Gonzalez case. But a closer look at those supporters shows many are funded by and linked to Google. By deploying its paid allies in this way, Google helps to build an impression of broad-based support for its views of how the internet should run.

This is consistent with Google’s playbook over the last decade. The company has built up an army of proxies that can help make its case in legal, legislative, and regulatory debates in Washington. The Supreme Court, which is about to hear a critical case that could change how Big Tech platforms operate, is the latest target of Google’s influence machine.

1https://projects.propublica.org/nonprofits/organizations/480918408/201823199349104557/IRS990PF

https://web.archive.org/web/20220311190334/https:/kstatic.googleusercontent.com/files/565eb487f8cf9f96af89a4147ee79eb4cf3989d3c3953197b1e36e65e132b57ffaebccfb03ed62c57b8ffc5cd83654686f6b5160a97d3b561bc65ce5206012e9

https://projects.propublica.org/nonprofits/organizations/480918408/202013219349105781/IRS990PF

https://web.archive.org/web/20220311190334/https:/kstatic.googleusercontent.com/files/565eb487f8cf9f96af89a4147ee79eb4cf3989d3c3953197b1e36e65e132b57ffaebccfb03ed62c57b8ffc5cd83654686f6b5160a97d3b561bc65ce5206012e9

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/may/02/charles-koch-gave-25m-to-our-university-has-it-become-a-rightwing-mouthpiece

https://web.archive.org/web/20220311190334/https:/kstatic.googleusercontent.com/files/565eb487f8cf9f96af89a4147ee79eb4cf3989d3c3953197b1e36e65e132b57ffaebccfb03ed62c57b8ffc5cd83654686f6b5160a97d3b561bc65ce5206012e9