Google is more likely to show ads for so-called crisis pregnancy centers to lower-income users in two major U.S. cities, helping organizations that critics call “fake abortion clinics” reach underprivileged women, a Tech Transparency Project (TTP) investigation found.

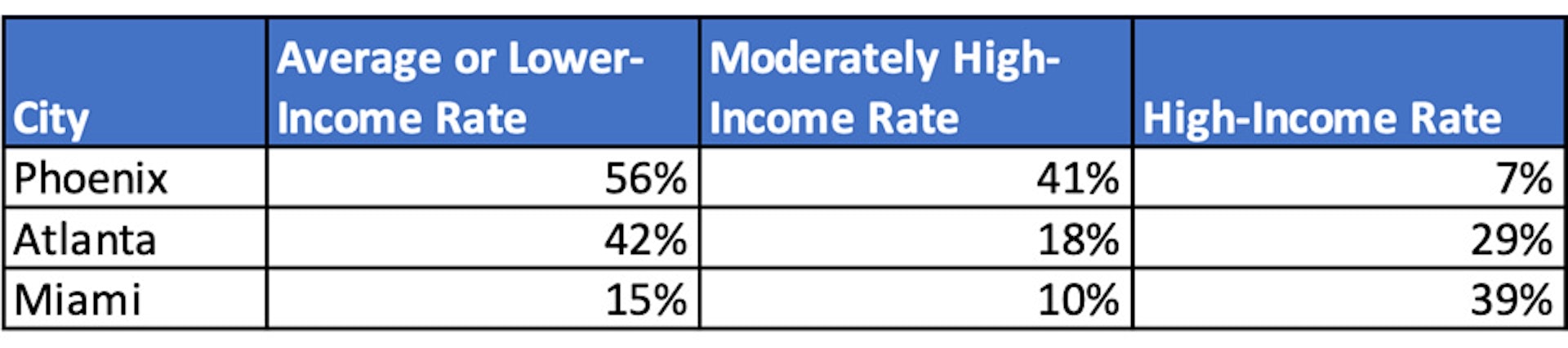

Our investigation found that when a TTP-created Google account identifying as a lower- or average-income woman in Phoenix searched for information on how to get an abortion, more than half the search ads (56%) served by Google came from crisis pregnancy centers. That’s a far higher rate than what test accounts for moderately high-income and high-income women from the same city received. A similar pattern emerged with a test account representing a lower- or average-income woman in Atlanta, which got a higher rate of crisis pregnancy center ads (42%) than women at the other income levels.

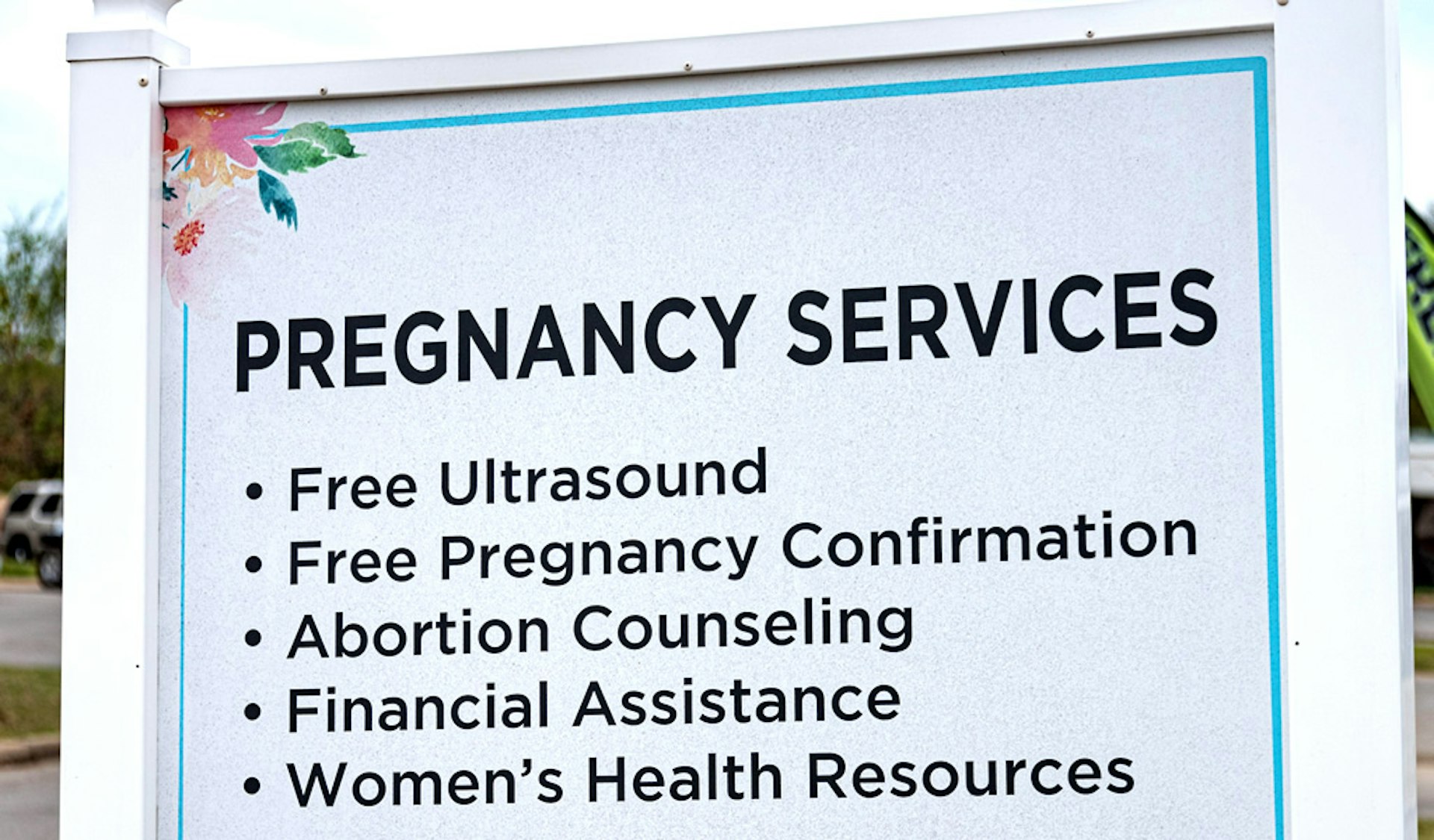

Crisis pregnancy centers—which critics have dubbed “fake abortion clinics”—appear to offer medical services but instead push an anti-abortion message, providing free ultrasounds and baby supplies with the aim of persuading women to carry unwanted pregnancies to term. Abortion rights advocates accuse them of using deceptive tactics to get women in the door—and targeting their advertising at low-income women and women of color in urban areas.

TTP’s findings add to growing questions about Google’s handling of crisis pregnancy centers, an issue that has come under increased scrutiny since the Supreme Court overturned the constitutional right to abortion last year. Bloomberg News has reported that Google Maps routinely misdirected users searching for abortion clinics to crisis pregnancy centers and that Google often failed to affix a warning, as promised, to crisis pregnancy center ads indicating they do not provide abortions. (In response to the first report, Google pledged to clearly label U.S. facilities that provide abortions in Google Maps and search results.) Last fall, TTP also found that Google frequently served ads for crisis pregnancy centers that falsely suggest they offer abortions, violating the platform’s policy against advertising that misleads users.

Not all cities in TTP’s new investigation showed the same pattern with Google crisis pregnancy center ads. In Miami, a test account for a high-income woman got the ads at the highest rate (39%). It’s not clear why Miami diverged from the other cities, but one possibility is that crisis pregnancy centers, which often seek to delay women’s abortion decisions until they are past the legal window for the procedure, are more actively targeting lower-income women in states like Arizona and Georgia, which have more restrictive abortion laws than Florida.

Methodology and results

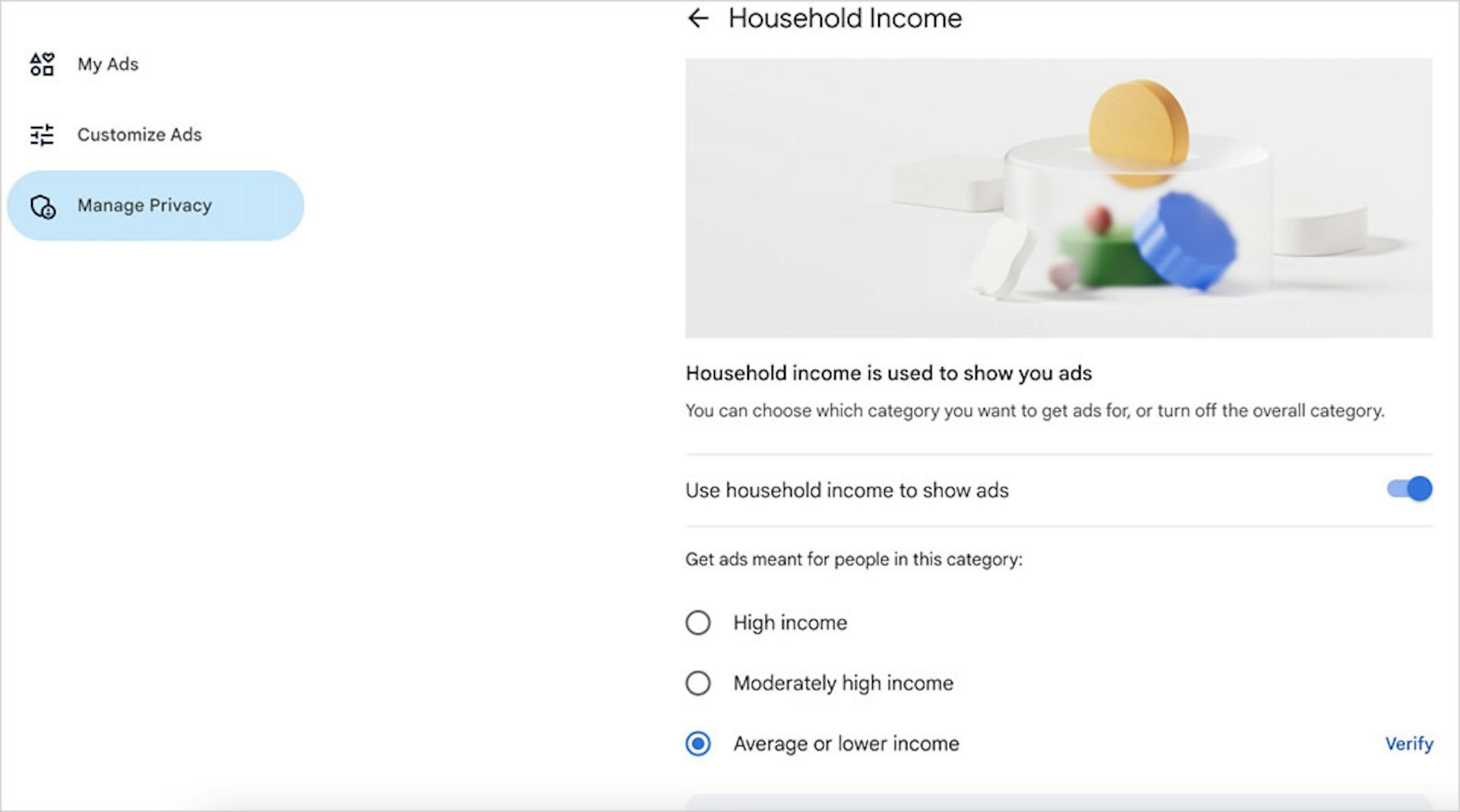

For this report, TTP registered Google accounts for test users in three cities: Phoenix, Atlanta, and Miami. TTP set up all the accounts as a woman born in 1992. Then within each account’s advertisement personalization settings, researchers selected a household income category. Each city got three accounts assigned to different household incomes as defined by Google: Average or lower income, moderately high income, and high income.

Using a clean version of the Google Chrome browser with no prior browsing history, TTP did 15 abortion-related Google searches while logged into each account. (The searches included “Abortion clinic near me and “I want an abortion.”)1 TTP then recorded every ad that appeared on the first five pages of search results. Our researchers used virtual private networks (VPNs) to make it appear the users were searching from Phoenix, Atlanta, or Miami.

In two of the cities, Phoenix and Atlanta, Google served crisis pregnancy center ads at a higher rate to the test users on the lower end of the income scale. For the Phoenix lower- or average-income woman, 56% of the ads came from crisis pregnancy centers, more than Google served to the moderately high-income (41%) and high-income women (7%) in that city. In Atlanta, the lower- or average-income woman saw 42% of her ads come from crisis pregnancy centers, higher than what moderately high-income (18%) and high-income women (29%) received.

By serving a higher rate of crisis pregnancy center ads to lower-income women, Google is helping these centers reach their intended audience. Abortion rights groups and academic studies have noted that crisis pregnancy centers typically target women of lower socioeconomic classes, in part by advertising free services on public transportation and in bus shelters.

Crisis pregnancy centers, which are seeking to expand their reach following the Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade, are known to make heavy use of Google. A June 2022 report from the Center for Countering Digital Hate found that one in ten Google search results for “abortion clinic near me” and “abortion pill” in so-called trigger law states led to fake abortion clinics. (These states had laws on the books stipulating that if Roe v. Wade was overturned, an abortion ban would go into effect.)

One digital marketing firm that works with anti-abortion clients highlights the importance of Google to crisis pregnancy centers. The firm, Choose Life Marketing, promises to help the centers navigate Google’s rules to get into “top searches” and be “seen BEFORE your competitors.” Its tips include:

Google’s algorithm has a way of silencing anything that has a pro-life ‘agenda.’ To combat this, try using fewer pro-life terms and incorporate a neutral voice to attract the abortion-minded woman. For example, writing something like, “If you choose life and decide to keep your baby, we can help” might be silenced by Google. Another way to say this that is up to Google’s terms is, “If you are considering parenting, we can help.”

As to what women can expect to encounter in crisis pregnancy centers, Google reviews offer some insight. One reviewer of the Prestonwood Pregnancy Center in Texas wrote that employees “misdiagnosed how far along I was” and pressed her on whether she asked God to forgive her for her sins. Another woman who visited the same center said she expected to discuss abortion options but got a sonogram picture with the words “hi mom!” written on it. One reviewer of PRC Medical, a crisis pregnancy center in Georgia, said employees told her they would not administer a pregnancy test if her intention was to get an abortion.

Other noteworthy findings

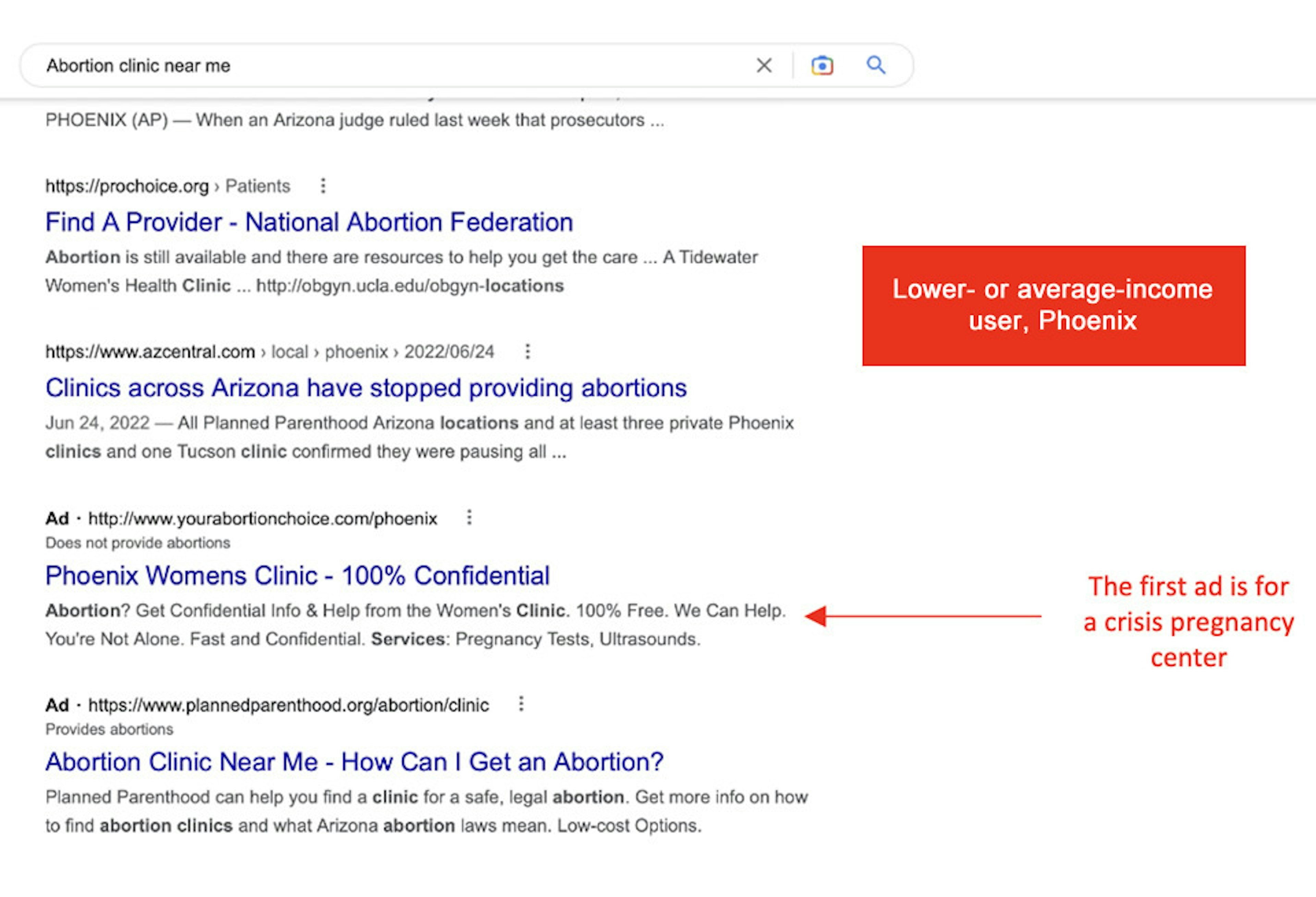

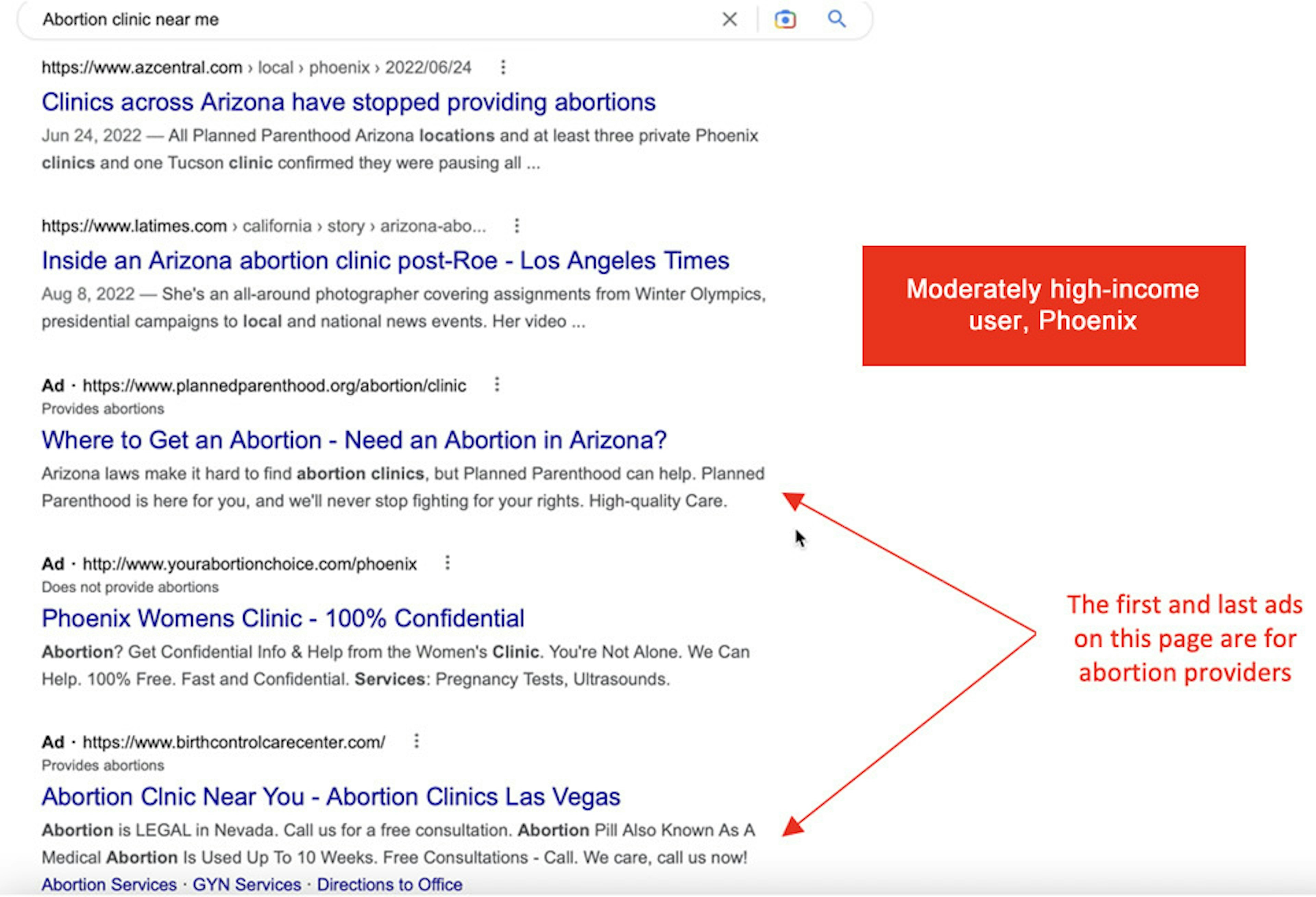

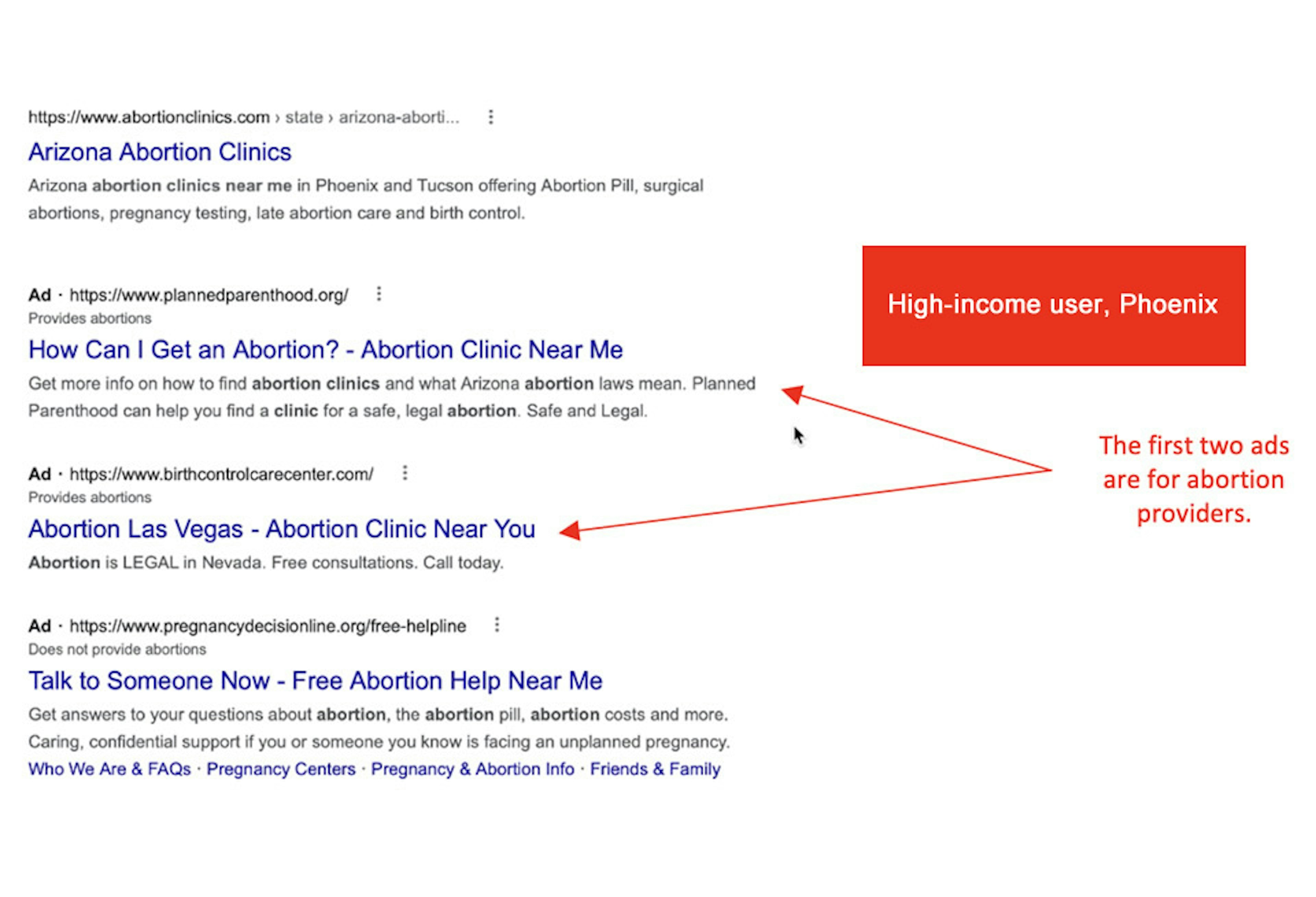

TTP’s investigation produced other insights into how Google serves crisis pregnancy center ads. For example, Google frequently served the ads higher up in the search results for lower-income women than it did for women of other income levels.

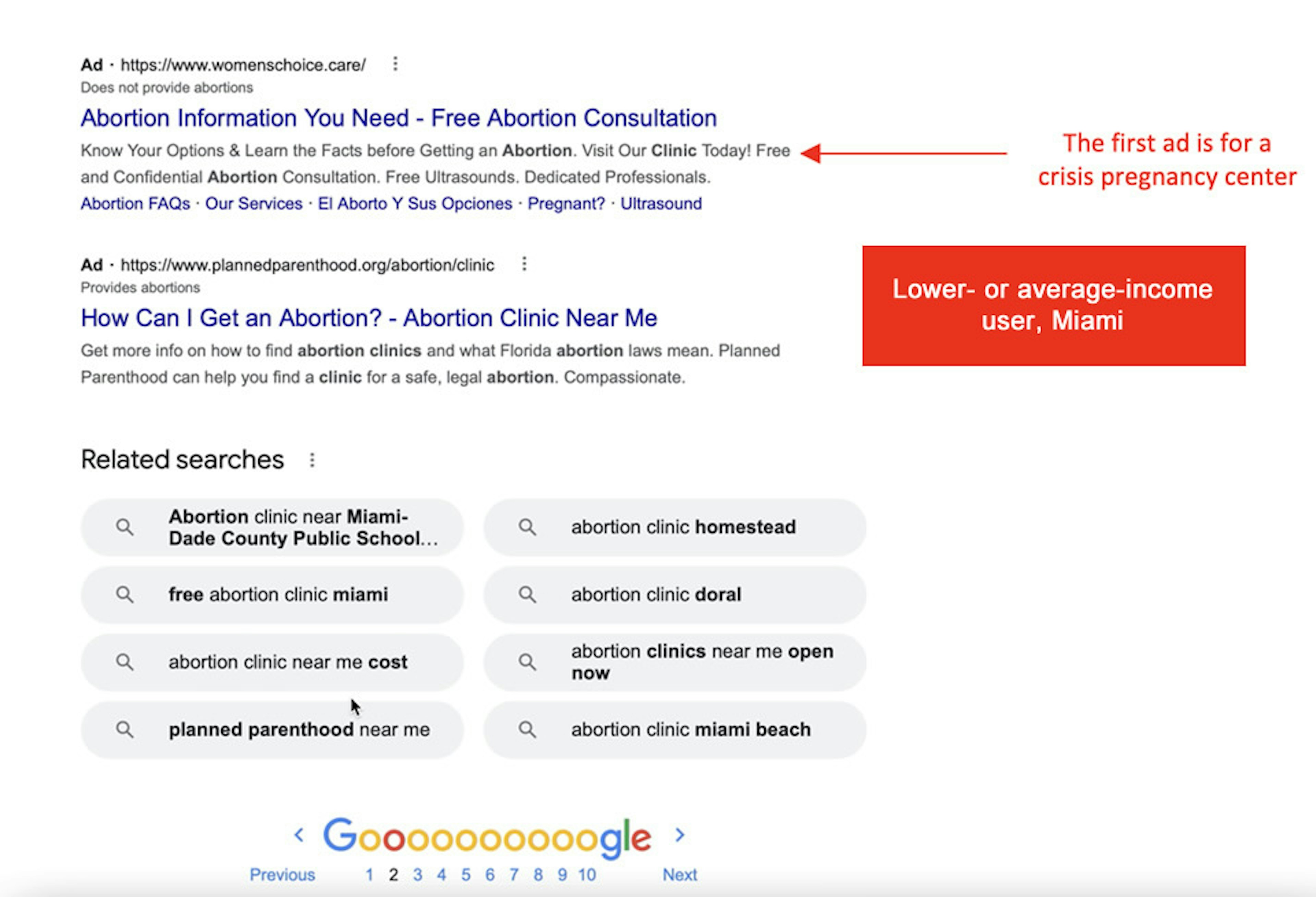

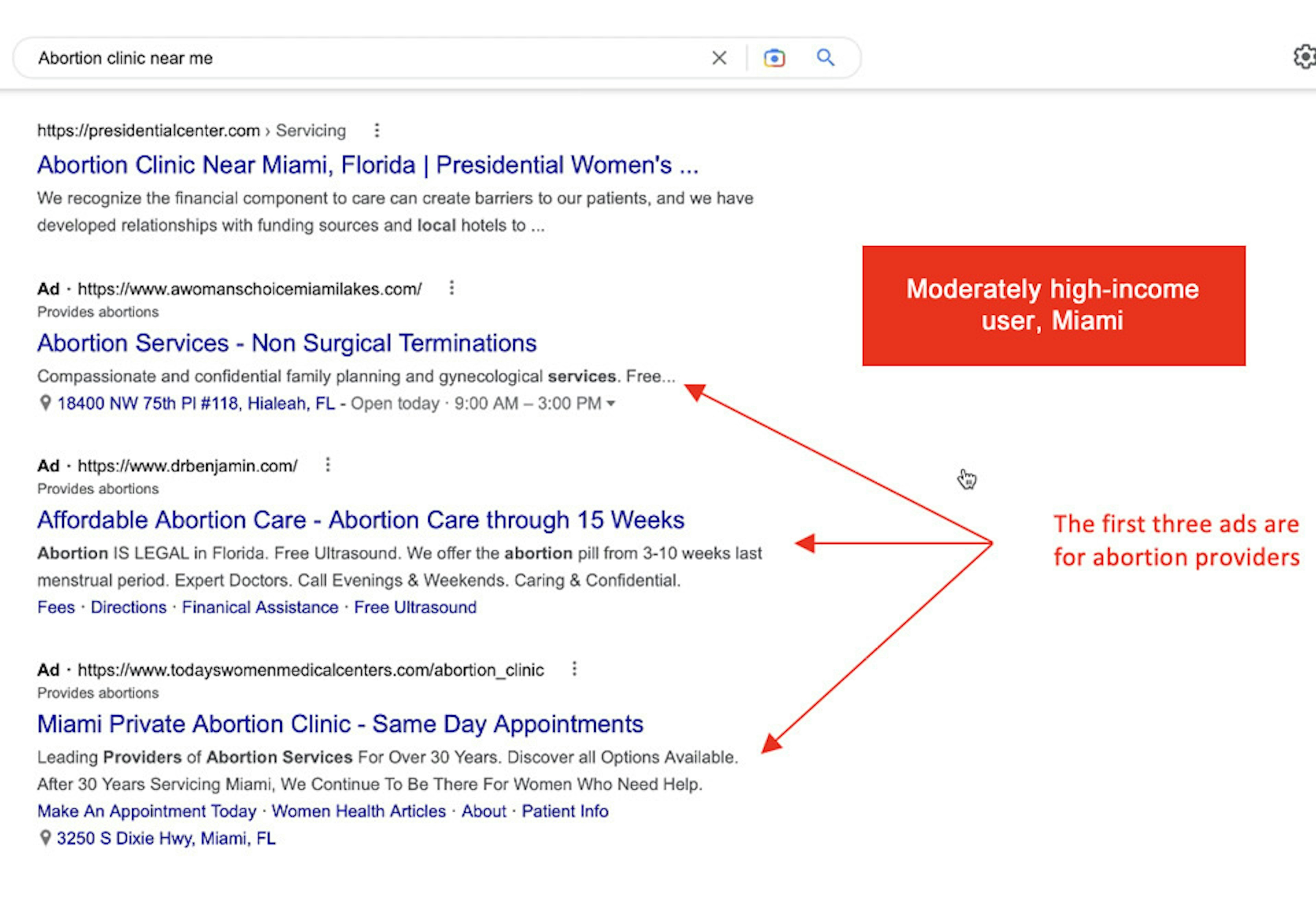

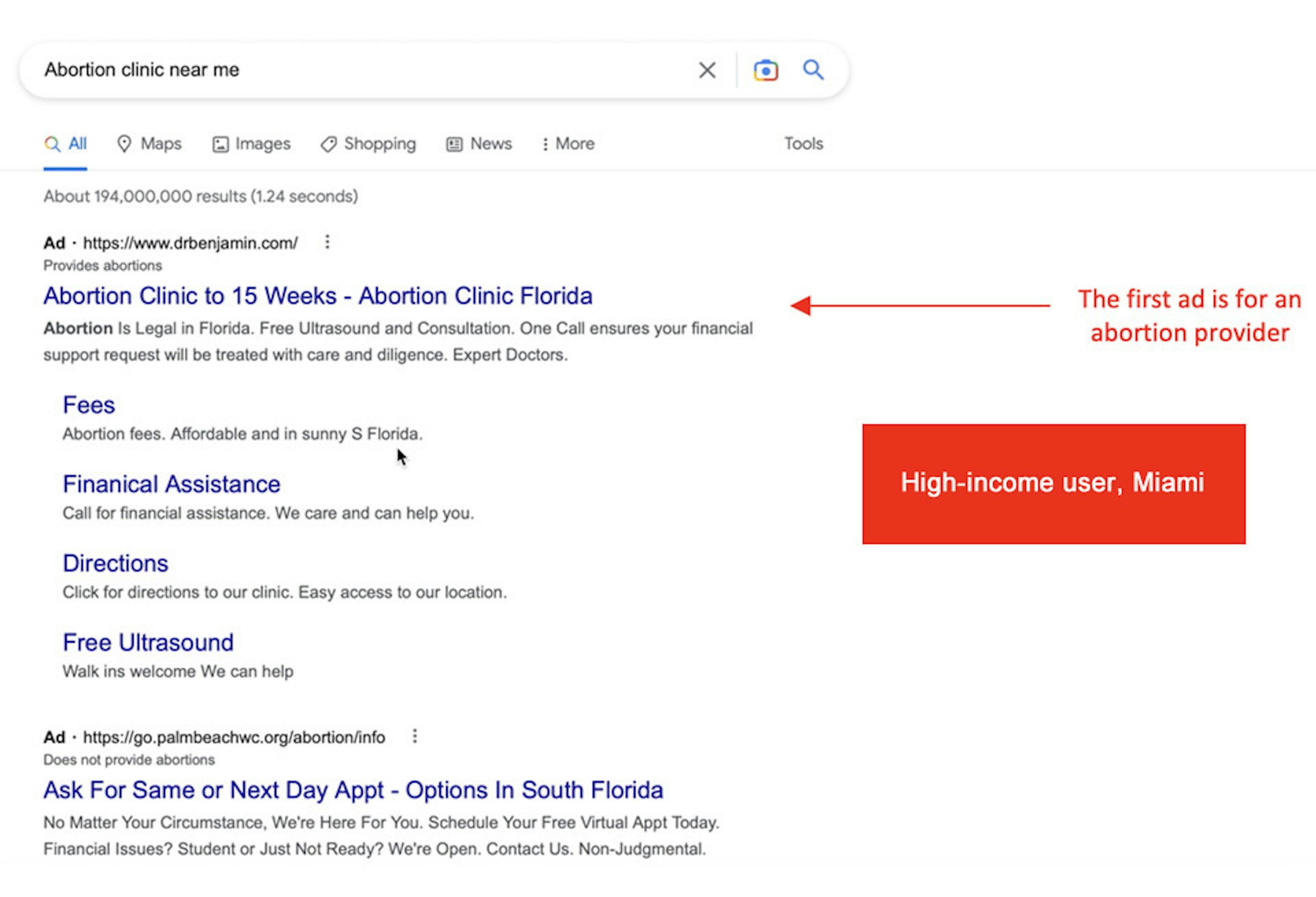

When the lower- or average-income test account in Phoenix searched for “abortion clinic near me,” the first ad served by Google came from a crisis pregnancy center. But when the moderately high-income and high-income accounts in Phoenix did the same search, they got their first ads from a Planned Parenthood clinic. Likewise, when the lower- or average-income user in Miami searched for “abortion clinic near me,” the first ad came from Women’s Choice Care, a network of crisis pregnancy centers in the Fort Lauderdale, Florida area. Meanwhile, the moderately high-income and high-income users in Miami who did the same search got their first ads from actual abortion providers.

Google says it determines “ad rank,” where ads are shown on a page, based on a variety of factors including how much the advertiser is willing to pay for a click, the quality of the ad and the advertiser’s landing page, and the competitiveness of the ad auction.

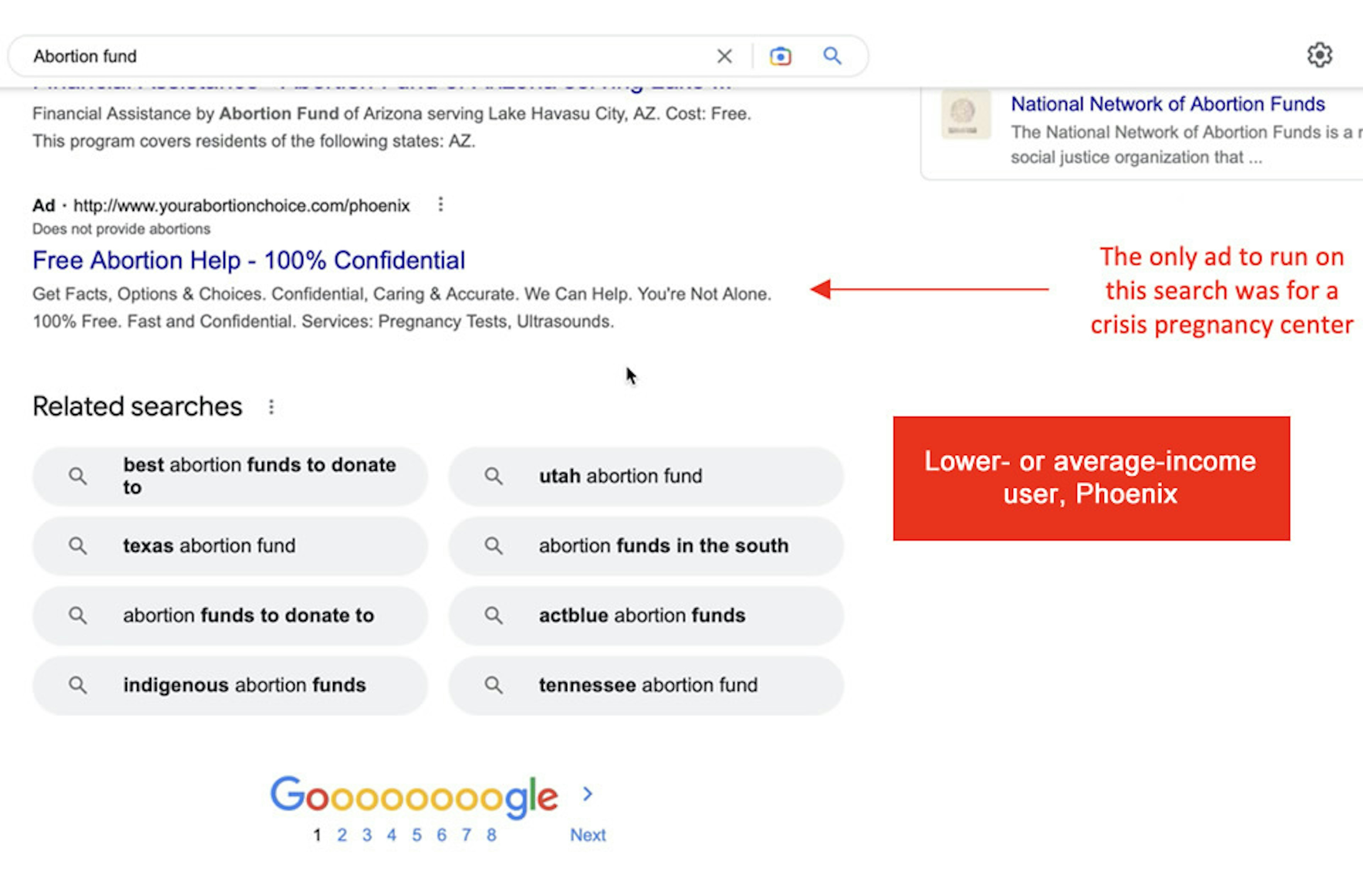

In several search queries in TTP’s experiment, the only ads Google served to lower-income users were for crisis pregnancy centers.

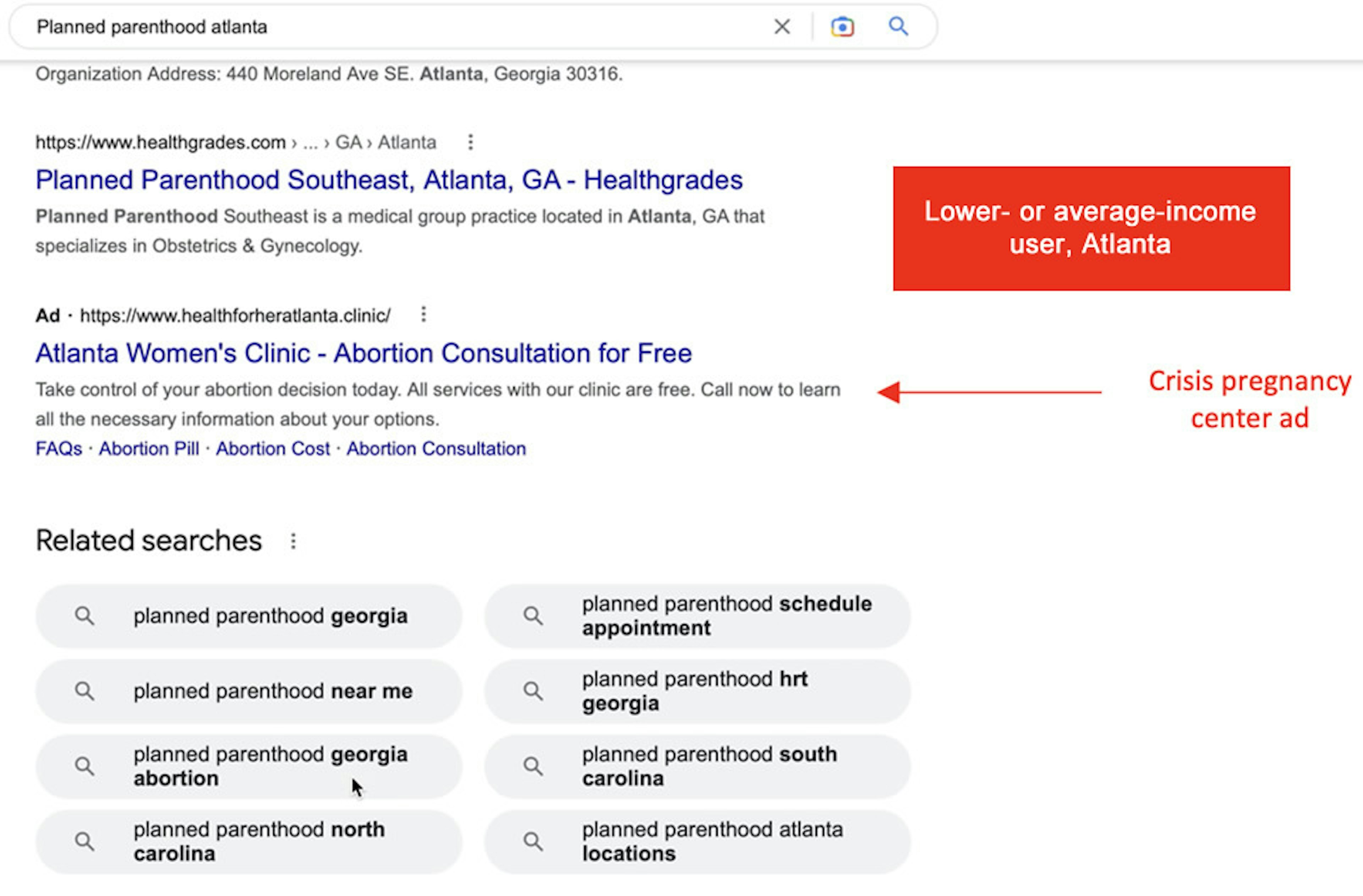

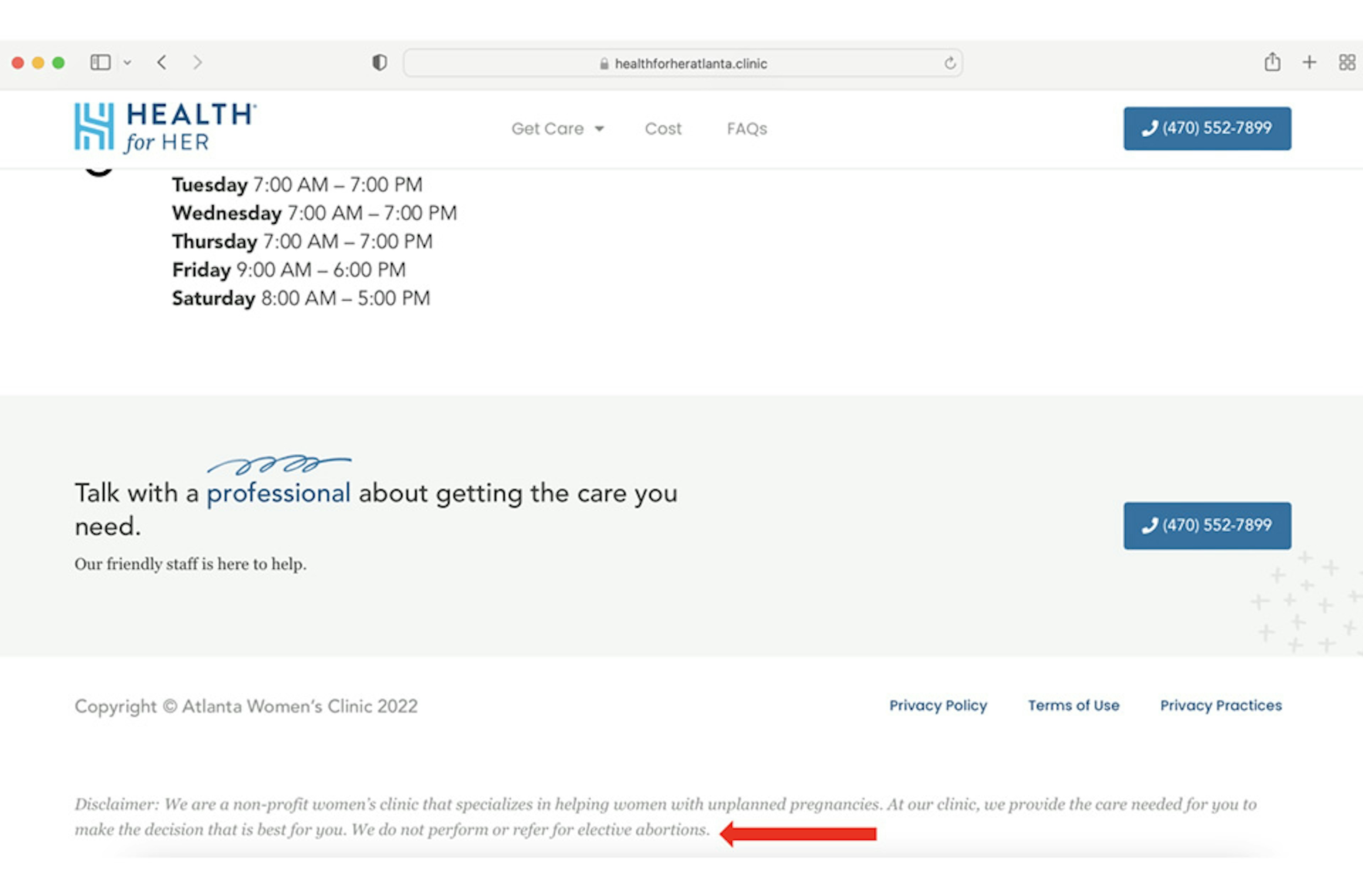

When the Phoenix lower- or average-income user searched for “Abortion fund,” the term for organizations that provide financial support for abortions, Google ran a single ad with the text “Free Abortion Help – 100% Confidential,” suggesting it can assist women with obtaining an abortion. But the ad links to the website of a crisis pregnancy center than offers services such as ultrasounds and a consultation on “pregnancy options.” When the lower- or average-income Atlanta user searched for “Planned Parenthood Atlanta,” Google produced a single ad that read, “Abortion Consultation for Free.” But the ad links to a crisis pregnancy center called Health for Her in Atlanta whose website discloses in small print at the bottom of the home page, “We do not perform or refer for elective abortions.”

As noted earlier, Google requires advertisers who run abortion-related ads to declare whether they do or do not provide abortions, generating a label that appears on the ads. But the Health for Her ad included no such label, indicating that either the crisis pregnancy center did not make the required self-declaration or Google failed to generate a label.

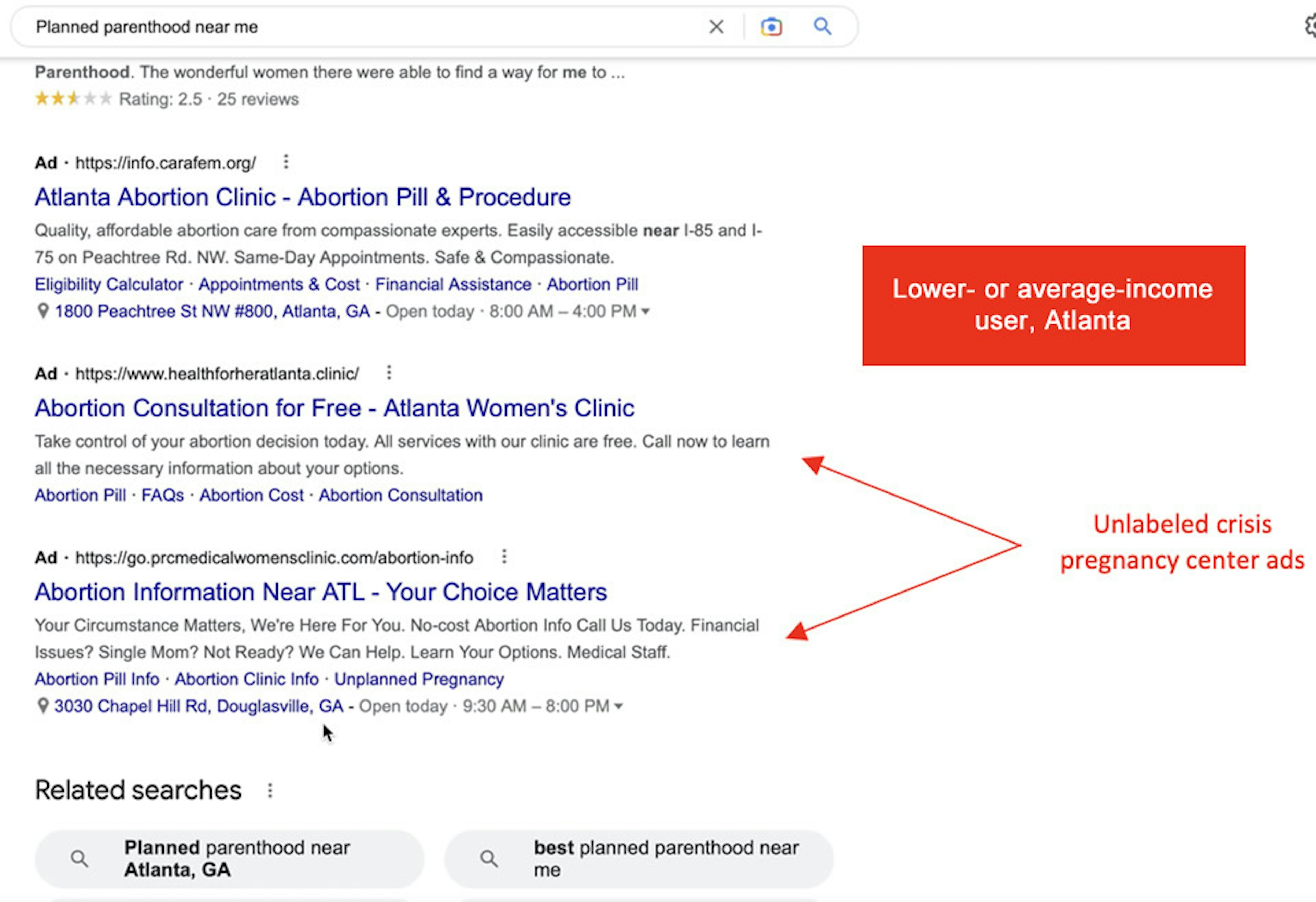

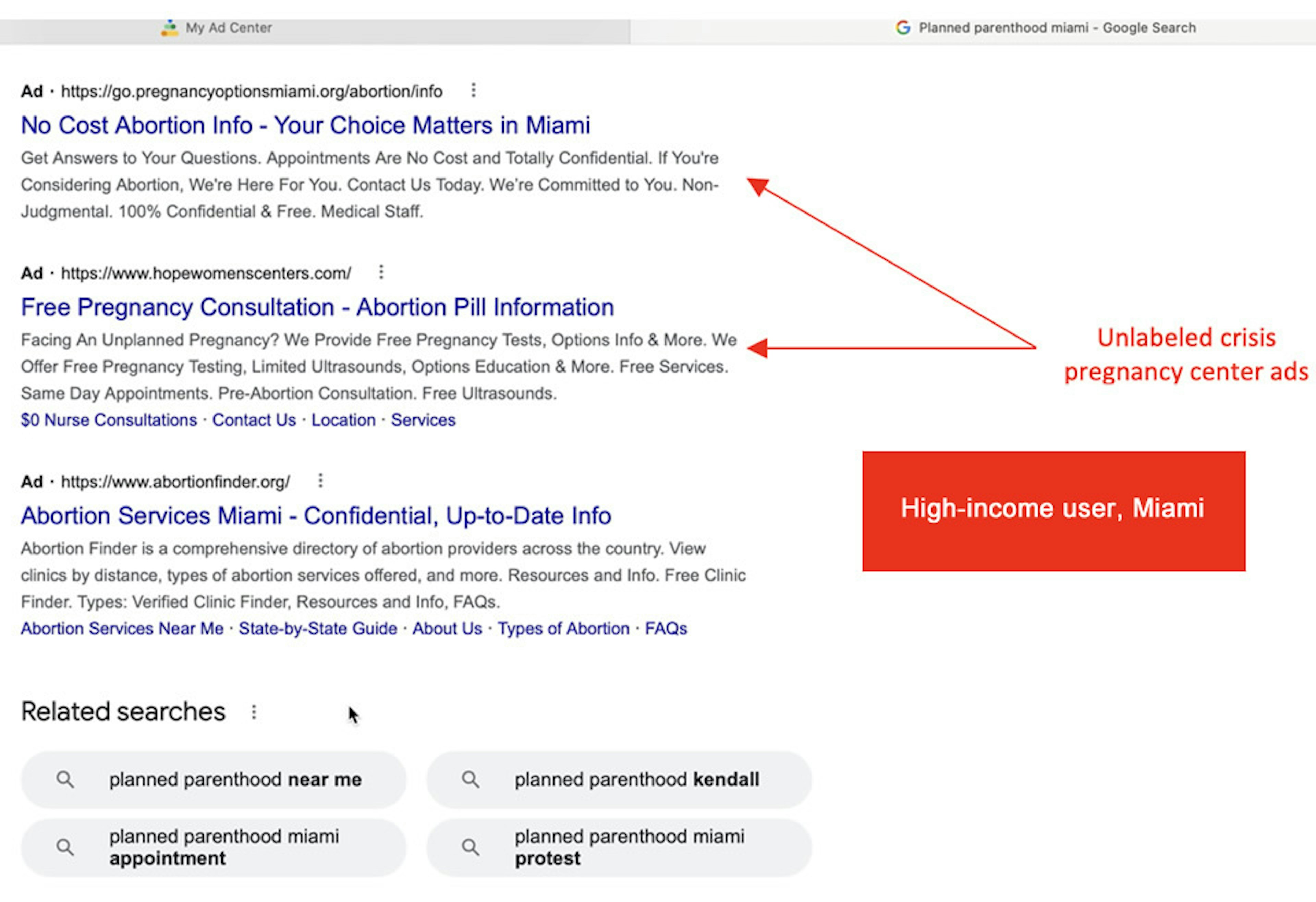

TTP found similar omissions in multiple ads examined during the investigation. For example, when the lower- or average-income woman in Atlanta searched for “Planned parenthood near me,” Google served four ads from crisis pregnancy centers that were missing the label that they do not provide abortions. When the high-income user based in Miami searched “Planned Parenthood Miami,” Google served crisis pregnancy center ads that read, “No Cost Abortion Info” and “Free Pregnancy Consultation,” with no label.

These findings are consistent with previous reporting about Google’s handling of crisis pregnancy ads, including its failure to consistently label such ads and its pattern of allowing ads that falsely suggest they offer abortion services in violation of Google’s policy on misrepresentation.

Conclusion

TTP’s new investigation adds to the growing body of evidence that Google plays a central role in the strategy of crisis pregnancy centers, which target low-income women and women of color using what abortion rights advocates call deceptive tactics and messaging.

These anti-abortion centers, which are aiming to expand their presence in the wake of the Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade, are poised to make even heavier use of Google in the years ahead—even as Google continues to fumble its labeling and policy enforcement for such advertising.

1 Search terms included: I want an abortion, Abortion clinic near me, Abortion *insert city name*, Planned Parenthood near me, Planned Parenthood *insert city name,* Are abortions safe, Abortion pill, Where to get an abortion, Abortion before 15 weeks, How to end pregnancy, Does insurance cover abortion, Loan for abortion, Abortion financing, Abortion cost, Abortion fund.