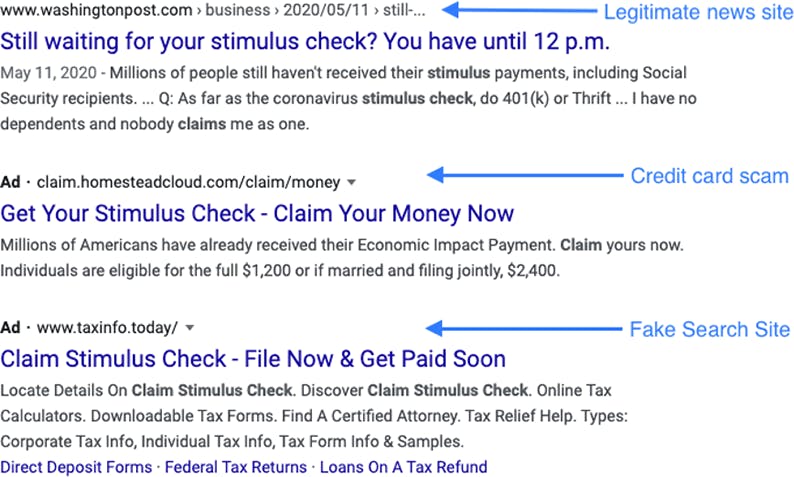

Google is helping scammers exploit anxious Americans searching for information about government relief during the coronavirus outbreak, according to a Tech Transparency Project (TTP) investigation, undermining the company’s claims that it’s working to protect people from pandemic-related fraud.

Many Americans have turned to Google for answers amid confusion over when they’ll receive stimulus payments of up to $1,200. Search trends data over the past three months have shown spikes for queries such as “where is my stimulus check,” “claim stimulus money,” and “government check.”

But TTP identified dozens of examples of Google targeting these searches with questionable ads aimed at exploiting financially distressed people. The ads direct users to sites that charge bogus fees for stimulus money, try to harvest people’s personal data, or plant unwanted software into their web browsers.

Many of these ads appear to violate Google’s own policies against misleading or fraudulent content. They also run counter to Google’s public efforts to combat coronavirus scams. The search giant even warned consumers in May that scammers have embraced new pandemic schemes “with alarming speed.”

The fact that Google is actively helping unscrupulous advertisers target cash-strapped Americans during the pandemic shows how even when the company promises to crack down on bad actors, the machinery of its advertising business doesn’t always play along—and may even make the problem worse.

As of mid-May, a reported 20 million people were still awaiting stimulus payments under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. Among those seeking government relief are low-income individuals who earn less than $12,200 a year, owe money to certain creditors, or do not have bank accounts.

Google has cashed in by selling targeted ads against people’s search queries about the stimulus. Advertisers pay Google on average between $1 and $2 every time someone clicks on one of these ads.

To investigate this dynamic, TTP, using a clean instance of the Google Chrome browser, searched Google for ten phrases that someone who is waiting for their payment might use: “IRS stimulus,” “stimulus check,” “where is my stimulus?,” “coronavirus stimulus,” “claim stimulus money,” “coronavirus money,” “government check,” “where is my coronavirus money?,” “where is my covid money?,” and “where is my government money?''

TTP then recorded all of the ads that displayed alongside each page of results and investigated each link. Of the 126 ads that we recorded, more than one third appeared to violate Google’s advertising policies. These ads promoted scams designed to extract personal or financial information, installed browser hijackers, redirected users to useless advertising sites, or advertised predatory financial “services.” (Read more about the methodology here.)

The exploitative ads on Google fall in five categories. We discuss each in detail below.

Credit card scams

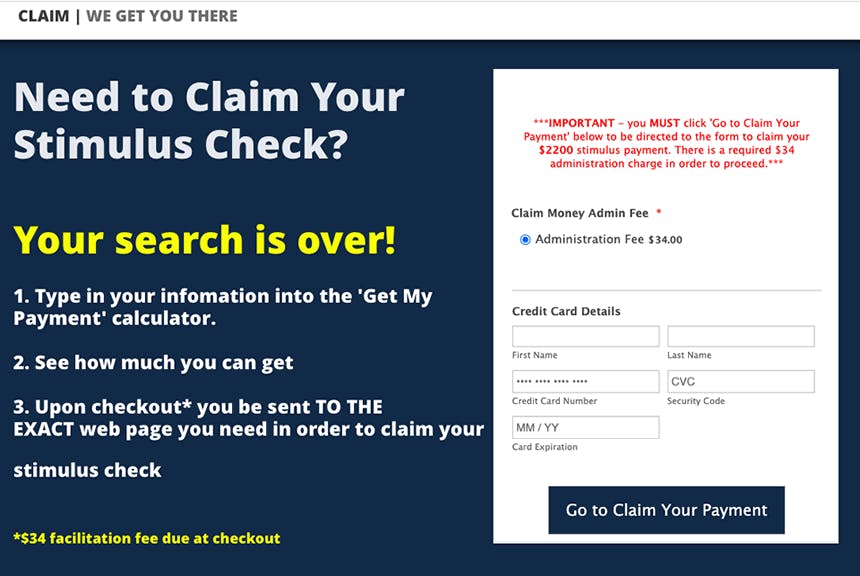

The first ad served alongside search results for “stimulus check” or “claim stimulus money” directed users to a website designed to elicit credit card information.

The site leads users through a screening questionnaire that purports to help users claim their stimulus money. Regardless of what is entered, the questionnaire always results in the same message that reads, “You haven’t received your payment because you need to fill out a simple form to get your money.” The page then prompts users to fill in their credit card information and pay a $34 “facilitation fee”—a tactic favored by scammers, the Federal Trade Commission has warned. The page was built using free web hosting services and is not connected with the IRS or any known financial services firm.

Google’s policies prohibit misrepresentation by advertisers or “enticing users to part with money or information under false or unclear pretenses.” The company considers dishonest business practices to be “an egregious violation of [its] policies.”

Watch how it works:

Personal data scams

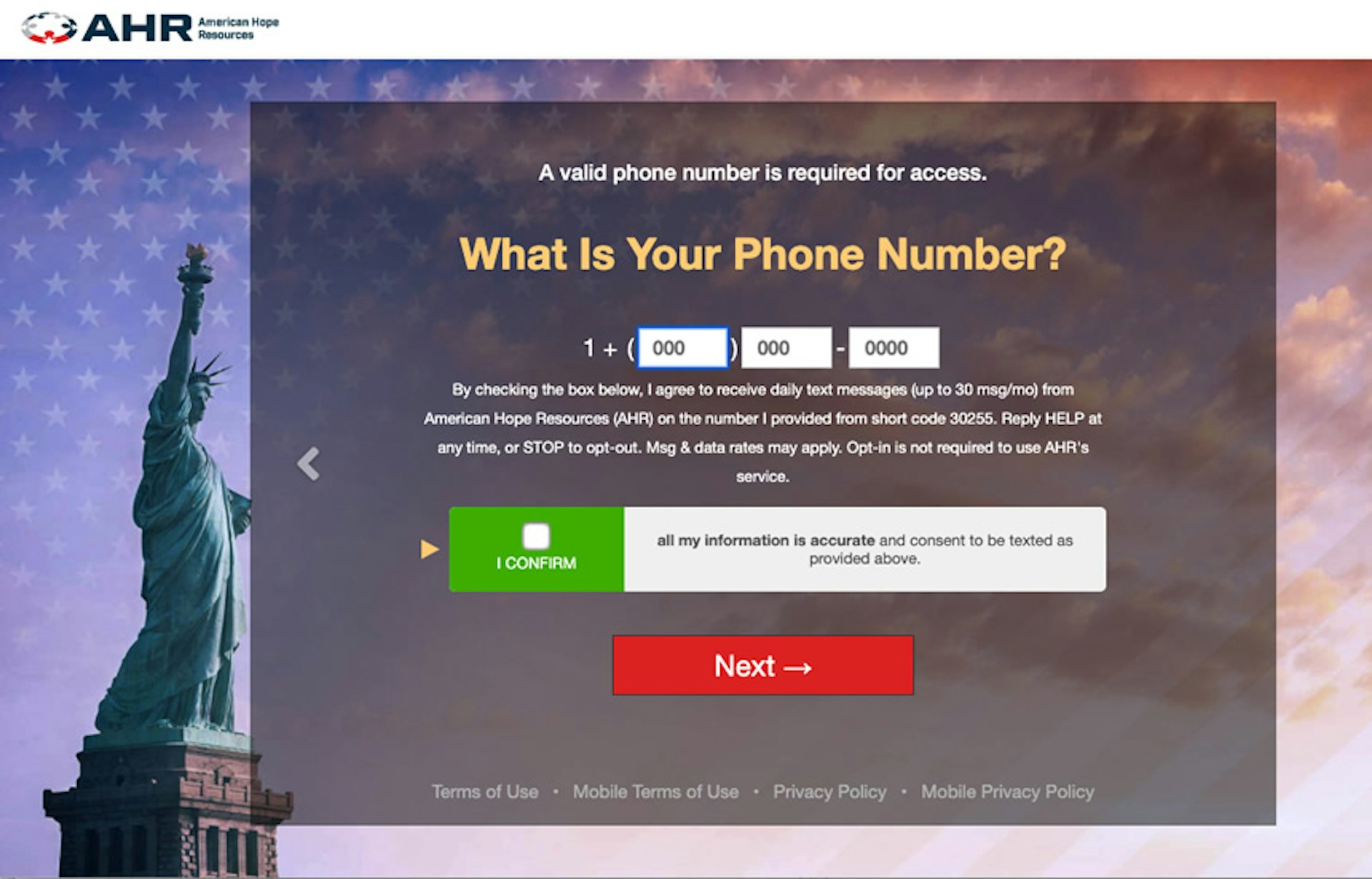

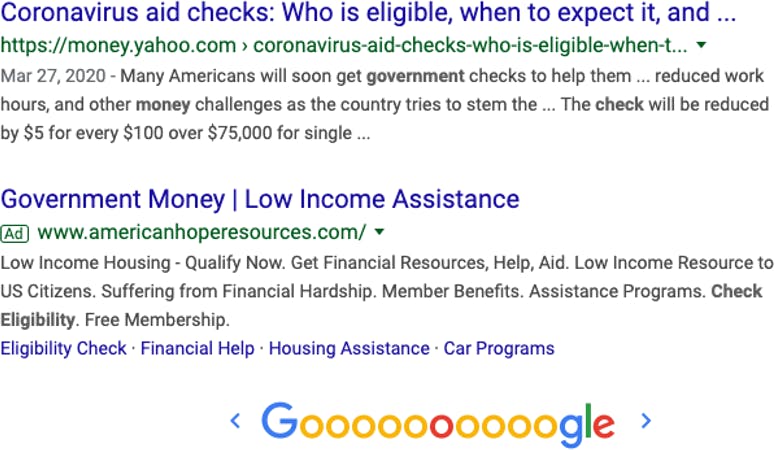

TTP identified eight ads for companies that collect consumer information for marketing purposes. With ad copy like “Low Income Housing - Qualify Now. Get Financial Resources, Help, Aid,” these ads trick users into thinking that they are applying for financial education or relief.

Clicking on these ads leads users to a sign-up form for various financial services (see here, here, and here). TTP was not able to find the promised services on these sites. But small, hard-to-read text states that submitting the form constitutes a request for marketing companies to receive the user's personal information. According to frustrated online reviewers, some of these sites and their partners also extract money or goods in exchange for bogus services.

Consumers have lodged at least 35 complaints against one Google advertiser, American Hope Resources, with the Better Business Bureau. Many of these complaints allege outright fraud. One self-described veteran said AHR scammed them into sending $3,000 worth of computer equipment to an unknown address so that the company could “install software” enabling work from home. AHR claimed that the equipment was lost during shipping, the person said.

Multiple posters also complained said that AHR asked them to send fees in exchange for grants or “guaranteed money packages.” One customer said, “I borrowed money from a lending company to pay the up-front fee. They lied about sending me the package.”

These ads appear to violate Google’s misrepresentation policy as well the company’s prohibition on collecting user data for unclear purposes.

Browser hijackers

During TTP’s test, Google served five ads for deceptive browser extensions alongside search results for “claim stimulus money.” These extensions, known as “browser hijackers,” modify users’ browser settings without their permission, to route web traffic through the servers of third-party companies that serve more ads and mine user data. Browser hijacker developers often sell this data, sometimes to cybercriminals.

The search ads identified by TTP had headlines like “File for Stimulus Benefits | Claim Benefits Online.” Clicking on the ads takes users to a page that prompts them to install a browser extension from the Chrome web store. Once the extension is installed, it sends users to more pages that direct them to install yet more extensions.

This process is known as “a dark pattern:” an interface specifically designed to trick people into doing something that they don’t really want to do. Over 100,000 people have installed one of the browser hijackers advertised on Google.

Watch how it works:

Internet security experts consider the browser hijackers advertised on Google to be “potentially unwanted applications” because the extensions are designed to make users install them unintentionally.

Google’s policies state that software marketed through Google should not “download or install additional software, or make system settings changes, beyond what was offered during the initial installation, unless it is doing so at the explicit, informed direction of the user.” The browser hijackers advertised on Google can also be difficult to remove, violating Google’s edict that information on how to uninstall must be easily accessible, simple to perform, and clearly identifiable after the software has been installed.

Third-party search sites

Many of the ads that Google serves alongside stimulus-related searches link to low-quality, third-party search sites. Like Google, these sites make money by showing targeted advertising alongside search results. Because these sites are not well-known, they attract visitors through arbitrage—in other words, they pay Google for ad space to generate clicks for their sites.

The third-party search sites register domain names related to specific topics and advertise them with copy to attract users. For example, the ad tech company System1 LLC advertises search pages with names like taxinfo.today and healthinfo.care to lure people seeking information on financial or health questions. An ad that directs to a generic search page on taxinfo.today reads, “Get Your Questions About IRS Where Is My Money Answered. Find Comprehensive Info About IRS Where Is My Money. Tax Relief Help. Online Tax Calculators.”

Google bans “driving traffic (through ‘arbitrage’ or other methods) to destinations with more ads than original content, little or no original content, or excessive advertising.” Google also prohibits ads that direct users to “doorway, gateway, other intermediate pages that are only used to link to other sites.”

Some third-party search sites identified by TTP also use Google’s advertising tools on their own domains. The result is a search page that is visually similar to Google, but with lower-quality results. Every third-party search site advertised alongside the searches in our study featured ads for browser hijackers on the first page of results.

Watch how it works:

Predatory financial services

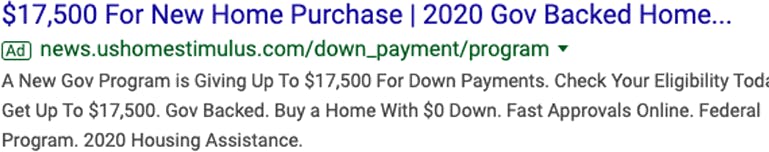

Google served at least seven ads for questionable financial marketing services alongside search results related to the stimulus. These included online courses that promise to help registrants make thousands of dollars through vague, internet marketing jobs and loan marketing pages that imply a connection to the U.S. government.

These ads appear to violate Google’s misrepresentation policy, which prohibits ads for “get rich quick” schemes and mimicry of government websites or agency names.

Multiple Better Business Bureau complaints describe being scammed by fake IRS sites that advertise on Google. One customer said these companies “use ads to place their company website first in the google search, and if you are unaware of the process, or distracted, or uninformed, it is very easy to think that the site is legitimate.” Users have also complained about this issue on Google’s own forums. Referring to ads for companies that charge users for free IRS employer identification numbers, one user said of Google, “I have reported this numerous times, they say they will look in to it, yet they're all still live. Why is this?”

Deception as a business model

As of January, search ads on Google feature the same type face and color scheme as organic search results, which can make them hard for users to identify. Some research suggests that recent design changes have made it more difficult for users to distinguish between ads and search results.

Google says it reviews “all content” in the ads on its platform before approval, but TTP’s investigation found that scam ads are often prominently displayed in Google’s search results. In some cases, the very first ad that Google served alongside searches for stimulus information linked to a scam.

The continued presence of these unscrupulous ads calls into question Google’s commitment to protecting people from Covid-19 scams and its promise to “keep you safe whenever you’re online.” By turning a blind eye to exploitative ads in its powerful search engine, Google shows its actions don’t match its rhetoric at a time of financial distress for many Americans.