Google is allowing scammers to prey on Americans seeking information about how to vote in the upcoming election, according to a Tech Transparency Project (TTP) analysis, undercutting the company’s claims that it’s helping people navigate the process of registering to vote, securing a mail-in ballot or finding their polling place.

The ongoing coronavirus pandemic is changing the way millions of Americans vote, and that makes access to accurate information about elections more important than ever. But citizens who turn to Google for answers could be discouraged or misled by scam ads that pop up as they search for how and where to vote in 2020.

TTP found that search terms like “register to vote,” “vote by mail,” and “where is my polling place” generated ads linking to websites that charge bogus fees for voter registration, harvest user data, or plant unwanted software on people’s browsers.

Such ads could have a suppressive effect on voters. Users searching for guidance about elections who instead find themselves on manipulative or confusing sites may eventually give up on finding the information they need. That’s a far cry from Google’s commitment to “protect our users from harm and abuse, especially during elections.”

The ads identified by TTP appear to violate Google’s policies that prohibit misrepresentation, collecting user data for unclear purposes, and unwanted software. They may also run afoul of Federal Trade Commission regulations banning “unfair or deceptive advertising.” TTP recently identified a similar dynamic with scam ads that target people searching Google for information about coronavirus stimulus checks.

With the 2020 election, Google has pledged to provide voters with “authoritative and objective information” and “tackle abuse on our platforms and help you navigate the democratic process before you head to the ballot box on November 3.” The company has also promoted voter registration tools and restricted microtargeting by political ads. But Google hasn’t protected voters from the scam ads that it regularly serves up in search results.

The first advertisement in a Google search for “register to vote,” for example, directed users to a website that seeks exorbitant fees to process voter registration forms. The site encourages users to hand over personal information, credit card data, and up to $129 to complete the task. No government agency in the United States charges for voter registration.

To explore how widespread this problem is, TTP used a clean instance of the Chrome browser to search Google for “absentee ballot,” “early voting,” “voter registration,” “vote by mail,” “register to vote,” “apply to vote,” “how to vote,” “absentee ballot application,” “where is my polling place,” “find polling place,” and “vote absentee.” TTP then clicked through all of the results associated with each phrase and recorded the ads served alongside them.

The analysis found that nearly one third of the ads—189 out of 613—directed users to sites that try to extract personal information for marketing purposes, install deceptive browser extensions, or bombard people with misleading or useless ads.

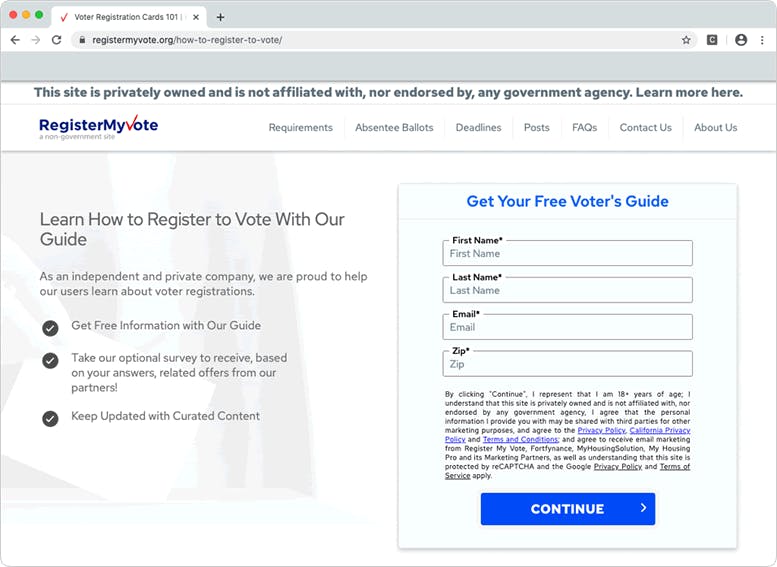

Google displayed a dozen ads alongside search results for “vote by mail,” “register to vote,” “apply to vote,” “how to vote,” and “absentee ballot” that pointed to registermyvote.org, a site that masquerades as a voter guide in order to collect visitors’ information for marketing purposes. Every link on the site led to a form that asked for users’ personal data, accompanied by small text disclosing that submitting the form constituted consent to receive marketing materials.

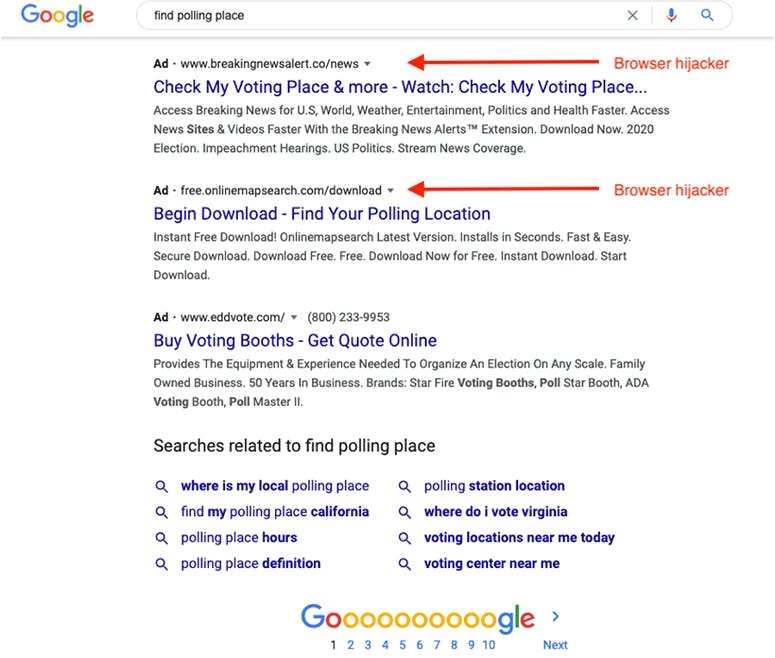

TTP also found that Google served 43 ads for so-called browser hijackers alongside the search terms “vote by mail,” “register to vote,” “absentee ballot,” “how to vote,” and “find polling place.” These browser extensions often use the promise of government forms or other useful information to induce people to install unwanted software that routes them to sites that serve more ads or harvest their data.

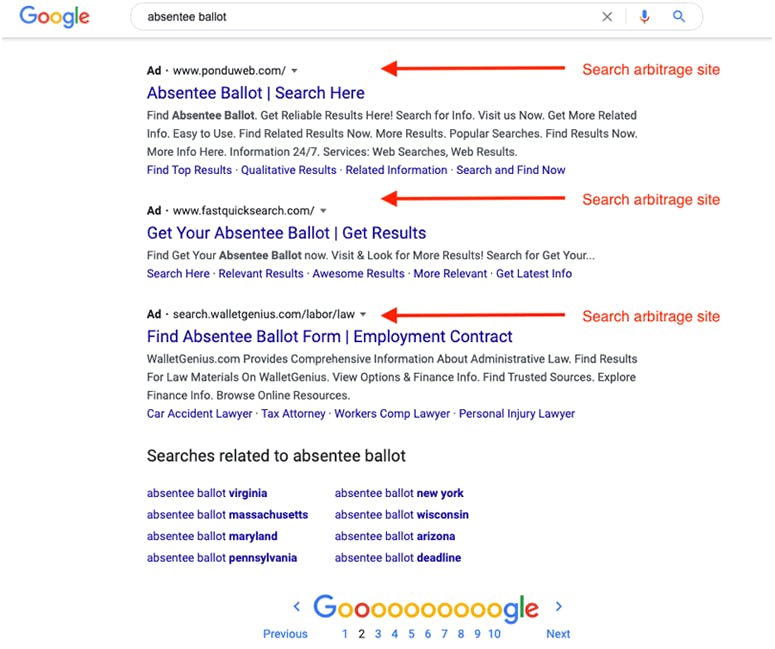

The analysis identified another 130 ads that directed users seeking election information to low-quality, third-party search sites. These “arbitrage” sites, which advertise on Google to generate clicks, often point users to more useless or unsavory sites, and voters who end up in this morass may eventually give up on their search.

Some people may find it difficult to distinguish Google ads from other kinds of content because as of January, search ads on Google feature the same type face and color scheme as organic search results.

These questionable ads are rampant on Google despite the company’s claims that it reviews the content of all of its advertising. Either Google is failing to review its ads carefully, or it is knowingly disseminating ads that could harm users looking for information on how to vote in 2020. Either way, it runs counter to Google’s stated belief that “American democracy relies on everyone’s participation in the political process.”