Google executives and employees bet heavily on a Clinton victory, hoping to extend the company’s influence on the Obama White House. They lost that bet, and are left scrambling to find an entrée to the Trump administration. Google’s playbook with Clinton reveals how the company most likely will seek to influence the new administration. There already are signs of that influence: Joshua Wright, who co-wrote a Google-funded paper while on the faculty of George Mason University and works at Google’s main antitrust law firm, has been advising the Trump transition team on competition issues. Alex Pollock, of the Google-funded R Street Institute, has also been named to oversee the transition at the FTC.

Introduction

Google’s extraordinarily close relationship with President Obama’s administration led to a long list of policy victories of incalculable value to its business. An in-depth examination of the company’s efforts to extend that special relationship into the next administration, which it wrongly predicted would be led by Hillary Clinton, reveal what we might expect from Google for the incoming Trump administration.

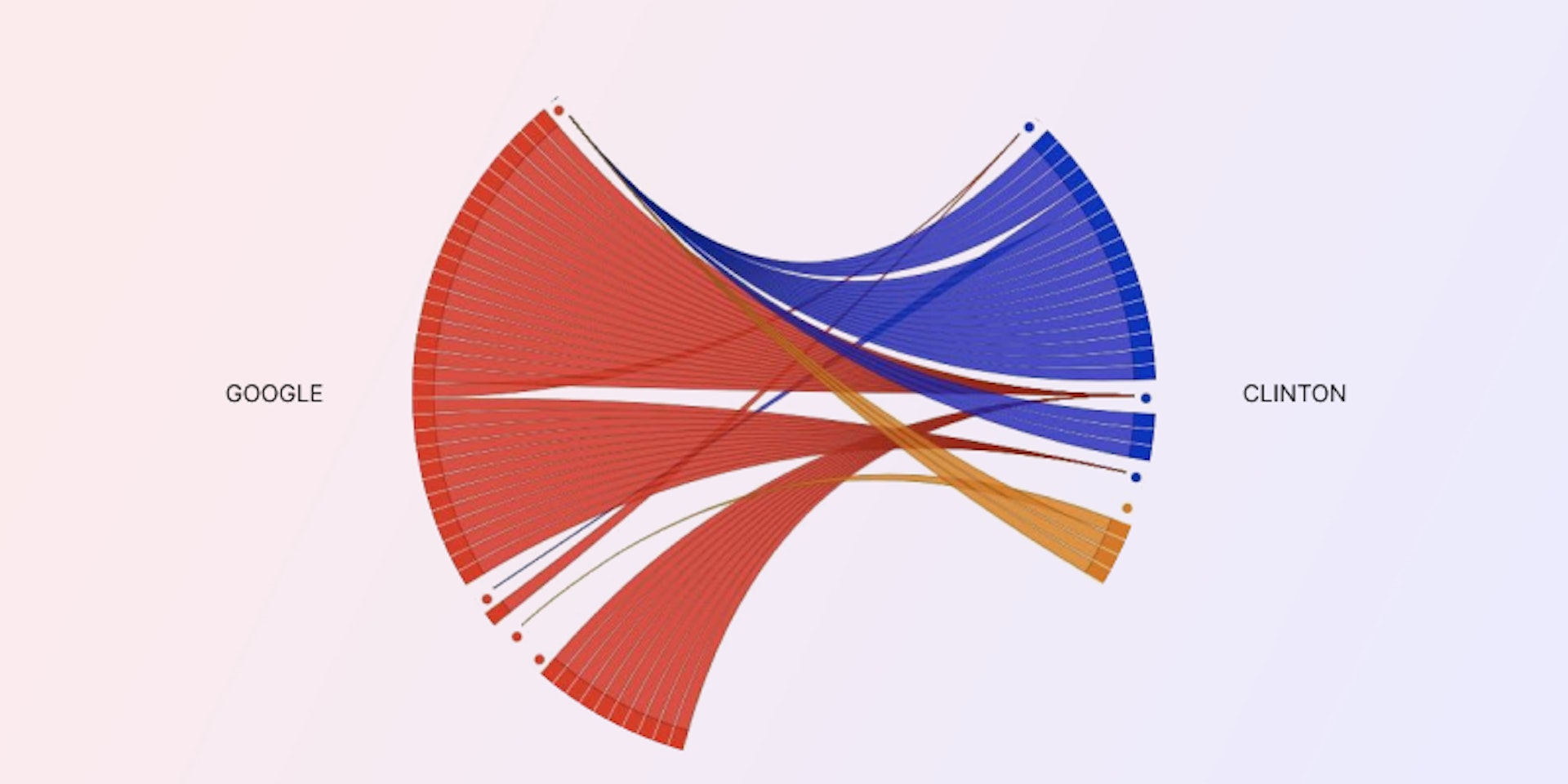

Google’s executives and employees employed a variety of strategies to elect Hillary Clinton and defeat Donald Trump. Google permeated Clinton’s sphere of influence on a broad scale, rivaling the influence it exerted over the Obama administration. A review found at least 57 people were affiliated with both Clinton—in her presidential campaign, in her State Department, at her family foundation—and with Google or related entities. In addition, 10 people who worked under Clinton at the State Department later joined the New America Foundation, a Google-friendly think tank where Google’s Eric Schmidt served as chairman and was one of its top donors.

Although the company and its chairman, Eric Schmidt, were ultimately unsuccessful in electing Clinton, their efforts underscore the profound and novel ways a corporation can influence our democracy beyond simple financial donations.

The Clinton campaign’s chief technology officer, Stephanie Hannon, came from Google, as did the campaign’s chief product officer, Osi Imeokparia. At least two other key Clinton campaign staffers, Derek Parham and Jason Rosenbaum, also previously worked at Google.

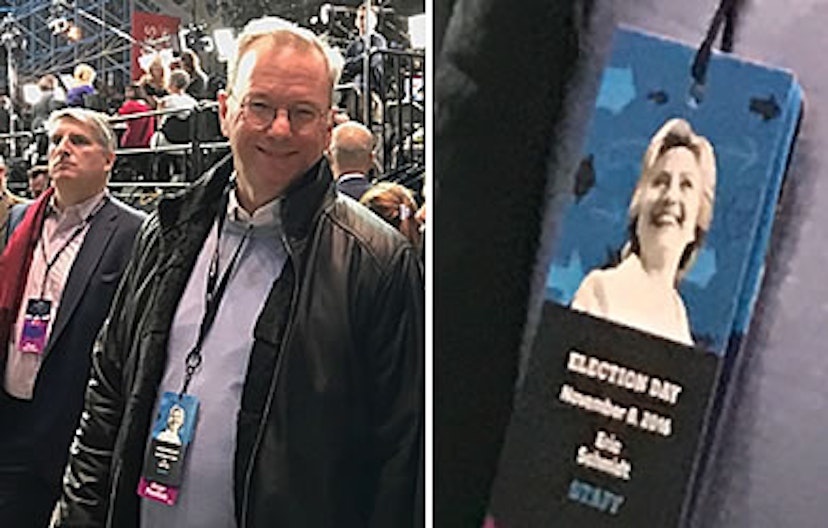

Left: Eric Schmidt at Clinton’s election night rally in New York, wearing a staff badge. Right: An enlargement of Schmidt’s staff badge on election night.

Several outside firms connected to Google also worked on the Clinton 2016 campaign. Those included Civis Analytics and The Groundwork, two companies that compiled data and polling on voters for the campaign and that were funded by Google’s Schmidt. Hillary for America spent more than $590,000 on services from The Groundwork and at least $48,000 on Civis Analytics in this campaign cycle. Clinton’s primary super PAC, Priorities USA, has spent more than $800,000 with Civis Analytics this cycle.

Had she won the election, Clinton would have been significantly indebted to Google and Schmidt, whom she has referred to as her “longtime friend.” For comparison, Schmidt’s future team at Civis Analytics was credited with helping produce his five million vote margin of victory during Obama’s 2012 election, and Schmidt subsequently enjoyed extensive access at the Obama White House.

Schmidt took on a similarly active role from the earliest days of the Clinton 2016 campaign, helping design, finance, and implement its digital voter-targeting operation. Internal campaign emails released by WikiLeaks show that Schmidt met with the team working on Clinton’s incipient campaign on April 2nd and 3rd, 2014, before it was even announced. Just three months after the meetings, with future campaign chairman John Podesta and former Clinton State Department aide Cheryl Mills, The Groundwork was incorporated and housed near the Clinton campaign headquarters to work on her voter-targeting effort.

Schmidt met regularly with Clinton advisors during the campaign to discuss issues such as where the voter-targeting operation should be located and how to compile all accessible information about voters in a single file. After meeting with Schmidt in April 2014, the future Clinton campaign chairman John Podesta reported: “he’s ready to fund, advise, recruit talent, etc.

Google’s support of Clinton extended beyond Eric Schmidt: the company over which he presides was a significant source of funds for both her campaign and her family foundation. Google is the Clinton campaign’s largest corporate contributor. Google employees, including at least six high-ranking executives, donated more than $1.3 million to Clinton’s 2016 campaign.

Google also is an annual financial supporter of the Clinton Global Initiative, a project of the Clinton Foundation. It has donated at least $9.6 million in grants to the foundation’s charitable initiatives and nonprofit members.

Had Clinton won the election, Google would have been able to capitalize on a close working relationship stretching back to her tenure as US Secretary of State. State Department officials travelled to Silicon Valley for meetings at Google’s headquarters attended by Schmidt, where they brainstormed how new technologies could be used to address diplomatic, development, and security concerns.

In recent years, Google has hired at least 19 officials from the Clinton State Department, including Jared Cohen, a member of Clinton’s policy planning staff. At Google, Cohen and Schmidt built a foreign policy think-tank, originally called Google Ideas and since renamed Jigsaw, that has carried out a wide range of missions, some in coordination with the State Department. As a Google executive, Cohen travelled to several conflict areas, raising suspicions that he was acting as an unofficial back-channel for the State Department. He reportedly narrowly avoided arrest during a 2011 trip to Egypt, where he met with a Google Middle East executive hours before the executive was detained for allegedly helping to incite the country’s revolution.

Had Clinton won the election, Google would have benefitted in current and new ventures from its extensive ties to her presidential campaign, her foundation, and the Clinton State Department. Several of those ventures rely on government funding or would be subject to regulatory scrutiny.

Beyond leaving its mark with Hillary Clinton, Google has proved highly adept during the past eight years at securing favorable decisions from federal agencies like the Federal Communications Commission, Federal Trade Commission, and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. It remains to be seen if the company can continue its influence under a Trump administration, but the role it recently assigned former FTC Commission Joshua Wright suggests the answer is yes.

Having failed to back the wining presidential candidate, Google is now seeking to soften its opposition to Trump. Schmidt congratulated Trump following his win, calling it an “amazing story.” He also praised Trump-backer Peter Thiel, calling himself a fan of the Silicon Valley investor and entrepreneur.

Google has spent heavily to woo Republicans in recent years and counter its image among conservatives as an arm of the Obama administration. Despite its support of Trump’s opponent, the company may benefit from a Trump administration if it is able to get friendly regulators appointed to his government. Joshua Wright, a former FTC commissioner, has been advising Trump's transition team and could return as chairman, for example. Wright is currently at Google’s main antitrust law firm, Wilson Sonsini, and previously wrote Google-funded papers arguing the company should not face antitrust action.

Alex Pollock, of the Google-funded R Street Institute, has also been named to oversee the FTC transition. The R Street Institute has produced a steady stream of Google-friendly policy papers and articles in recent years. Another possible FTC chair would be current FTC Commissioner Maureen Ohlhausen, who dissented from taking any action against Google in 2013, and has opposed taking aggressive action to increase competition or more aggressively protect privacy rights. It would be ironic if Google—having tried and failed to get Clinton elected—continued to benefit from officials at the FTC that have proven to be staunch defenders of the company in the past.