On March 15, 2024, Nick Clegg, Meta’s president of global affairs, touted his company’s efforts to fight drug addiction. Calling the opioid epidemic a “major public health issue,” he wrote that Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, had joined the Alliance to Prevent Drug Harms to “help disrupt the sale of synthetic drugs online.”

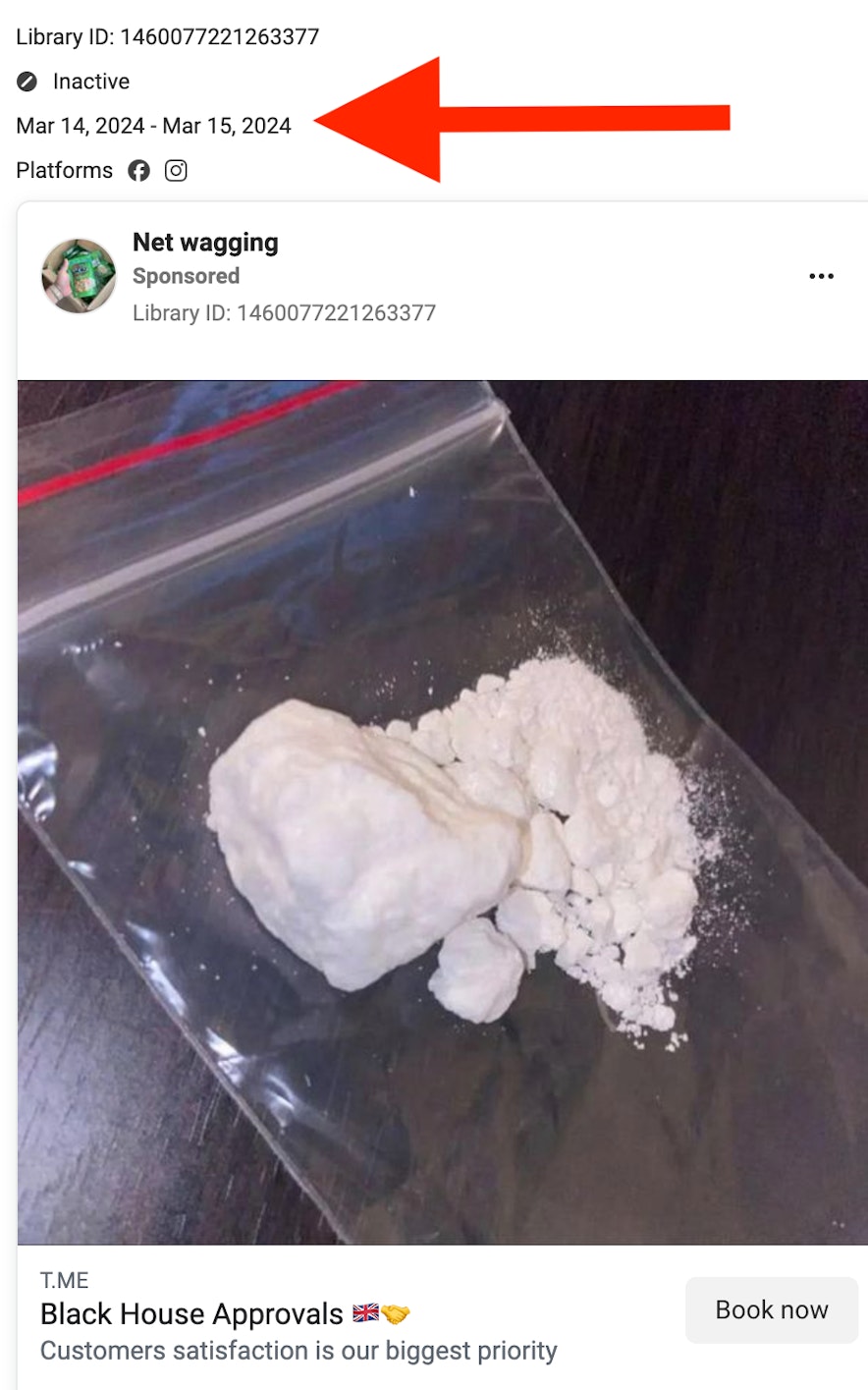

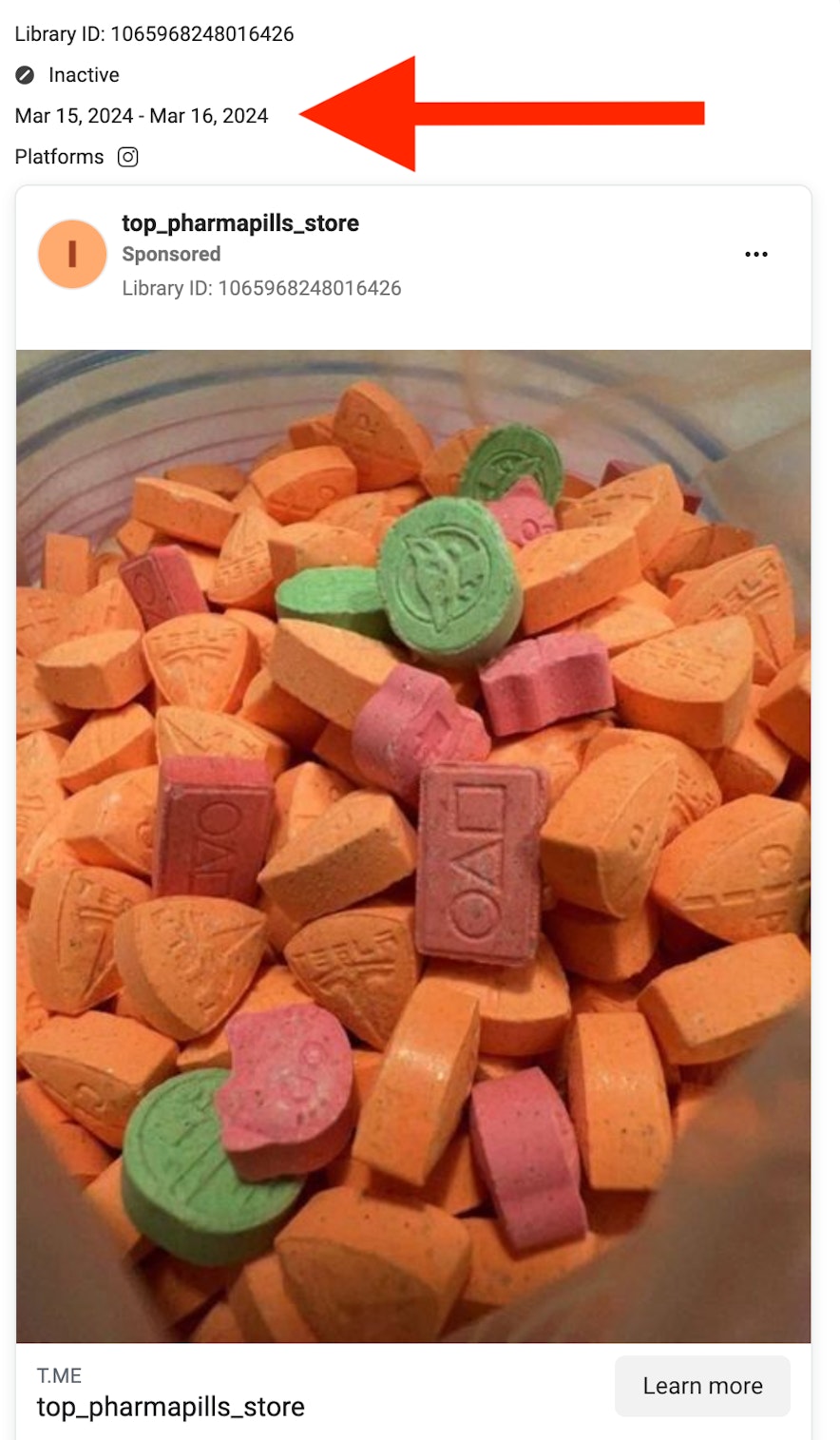

But Meta’s advertising engine, which generates the bulk of the company’s profits, evidently didn’t get the message. The same day Clegg made his announcement, Meta ran paid advertisements on its platforms selling opioids like oxycodone, tramadol, and Percocet as well as what appeared to be chunks of cocaine and ecstasy pills in violation of the company’s own policies.

This was not an isolated incident. A new investigation by the Tech Transparency Project (TTP) found more than 450 ads on Instagram and Facebook selling an array of pharmaceutical and other drugs. Many of the ads made no secret of their intentions, showing photos of prescription drug bottles, piles of pills and powders, or bricks of cocaine, and encouraging users to place orders. They often directed users to encrypted messaging apps Telegram or Meta’s WhatsApp to connect with sellers.

TTP’s findings undermine the reassurances offered by Meta executives like Clegg and CEO Mark Zuckerberg about the company’s efforts to stop the flow of drugs on its platforms. In the case of these ads, Meta is profiting from content that violates its policies and making potentially deadly drugs available to the public.

Meta has long been a useful tool for drug dealers. Investigations by TTP in 2021 and 2022 showed how Instagram allowed teens as young as 13 to find drugs for sale on the platform in as little as two clicks. In March, the day after Clegg posted about Meta joining the anti-drug alliance, the Wall Street Journal reported that U.S. federal prosecutors have been investigating Meta for facilitating the sale of illicit drugs.

Asked for comment about TTP's findings, a Meta spokesperson said, “Drug dealers are criminals who work across platforms and communities, which is why we work with law enforcement to help combat this activity. Our systems are designed to proactively detect and enforce against violating content, and we reject hundreds of thousands of ads for violating our drug policies."

"We continue to invest resources and further improve our enforcement on this kind of content," the spokesperson said, adding, "Our hearts go out to those suffering from the tragic consequences of this epidemic - it requires all of us to work together to stop it.”

Meta's president of global affairs, Nick Clegg, posted about his company's efforts to fight the opioid epidemic on March 15, 2024.

Meta's president of global affairs, Nick Clegg, posted about his company's efforts to fight the opioid epidemic on March 15, 2024.

Pills and powders

For this investigation, TTP searched the Meta Ad Library for the terms “OxyContin,” “oxycodone,” “Vicodin,” “Percocet,” “Xanax,” “codeine,” and “pure coke.” TTP also searched for the terms “WhatsApp” and “t.me,” the short link for Telegram. Both WhatsApp and Telegram are encrypted messaging apps that are known to be widely used by drug dealers. TTP conducted its research between March 1 and June 14, 2024.

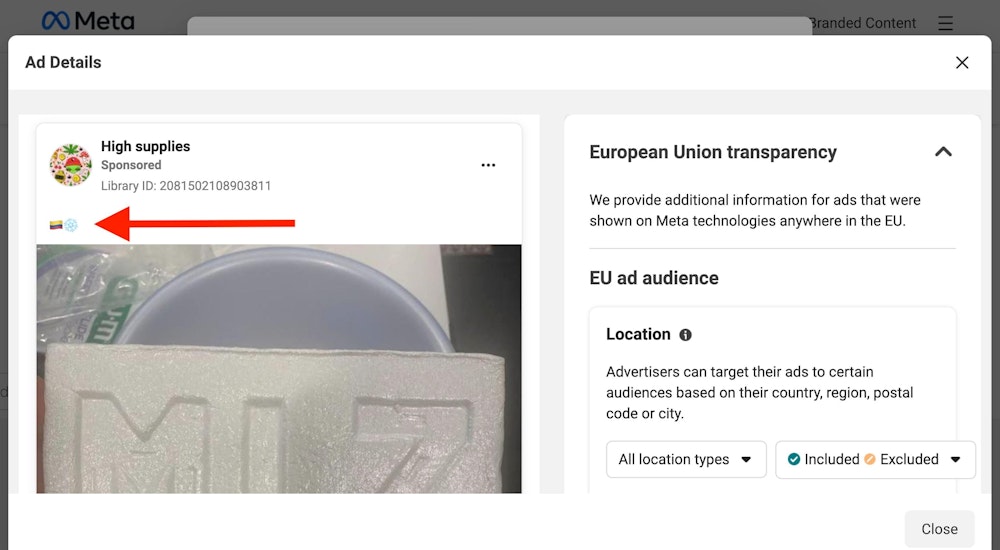

TTP found that searching the Meta Ad Library for the name of a prescription drug like OxyContin or Xanax often surfaced ads that explicitly sold the drug in question. These ads either named the drug in the ad text or showed a photo of a prescription drug bottle with the name of the medication clearly visible. Searches for the term “t.me” often surfaced ads that showed photos of pills, powders, crystallized substances, or bricks of white powder that appeared to be drugs like ecstasy or cocaine. These ads frequently had no text but linked to a Telegram account where a drug dealer listed specific products and prices. Some of these ads used known drug emojis, like a snowflake representing cocaine, to indicate their offerings.

Through these searches, TTP identified 452 drug ads that ran on Meta platforms, including Facebook, Instagram, Messenger, and Meta’s Audience Network, which places ads on mobile apps that partner with the service. Of all the platforms, Instagram hosted the highest number of drug ads: 405 of the 452 ads appeared on the photo-sharing site.

Because of the limitations of Meta’s Ad Library, TTP likely captured only a fraction of the drug ads that ran in the March-June time period covered by this report. According to Meta, the Ad Library only shows ads that are actively running on its platforms, with the exception of ads about politics, elections, or social issues, which it stores for seven years, and ads that run in the European Union, which it stores for a year. That means many ads on Meta platforms simply disappear from the Ad Library once they are no longer active, and there is no way to track them. TTP did not monitor the Ad Library continuously during its investigation, so the drug dealer ads it identified are in all likelihood an undercount.

TTP used the Ad Library’s location filter to search for ads that ran in the United States, the United Kingdom, and “all” locations. The Ad Library did not show the number of countries or individual users each ad reached, with one exception: If they ran in the European Union, Meta provided information on the location, age, and gender of EU users targeted by the ad and how many EU users the ad reached, in total and broken down by specific country. Meta says it provides this data to comply with transparency requirements of the EU’s Digital Services Act.

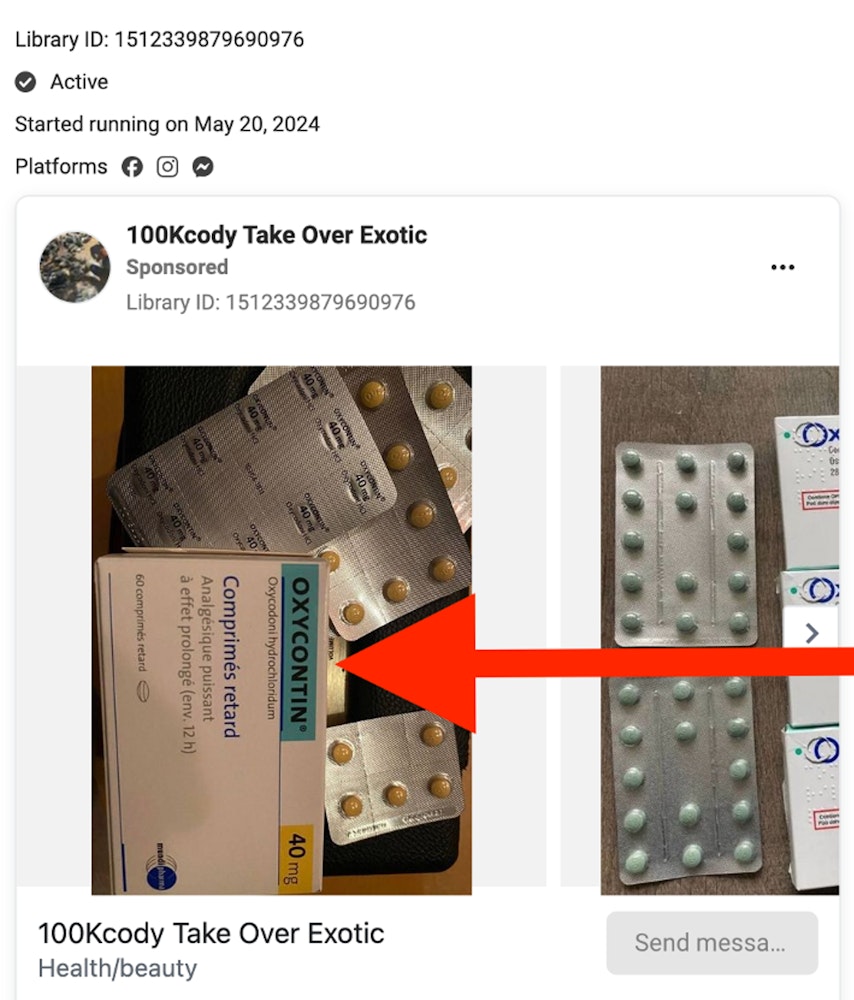

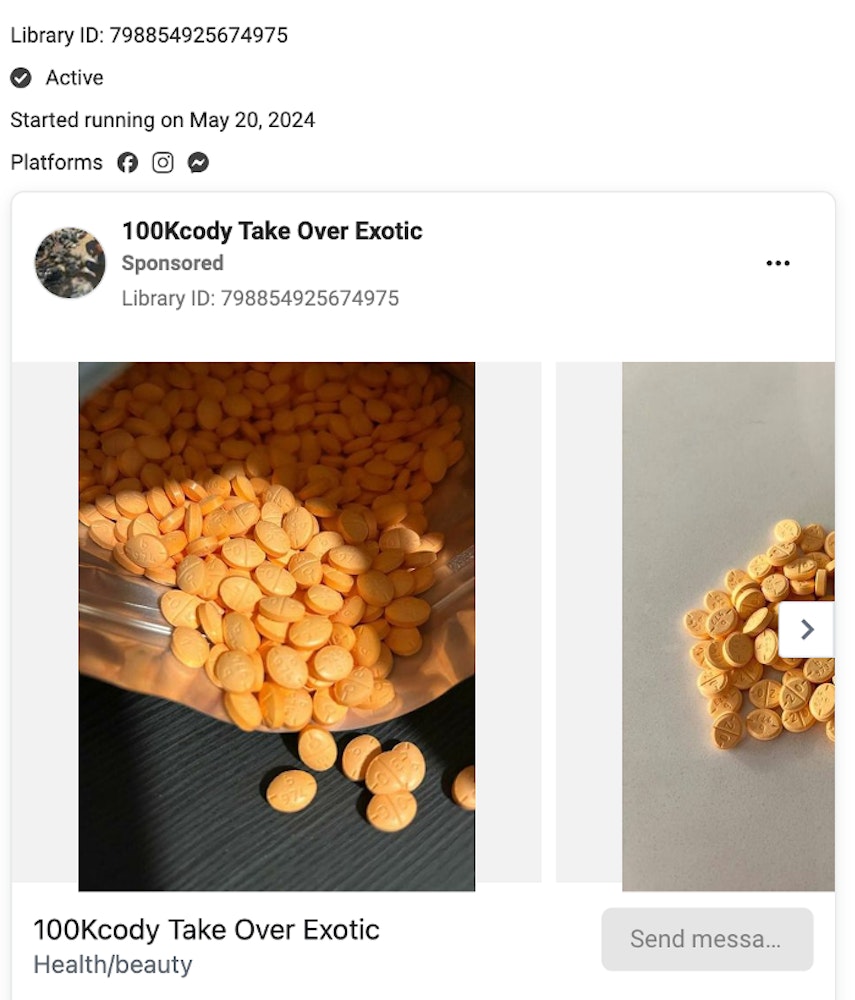

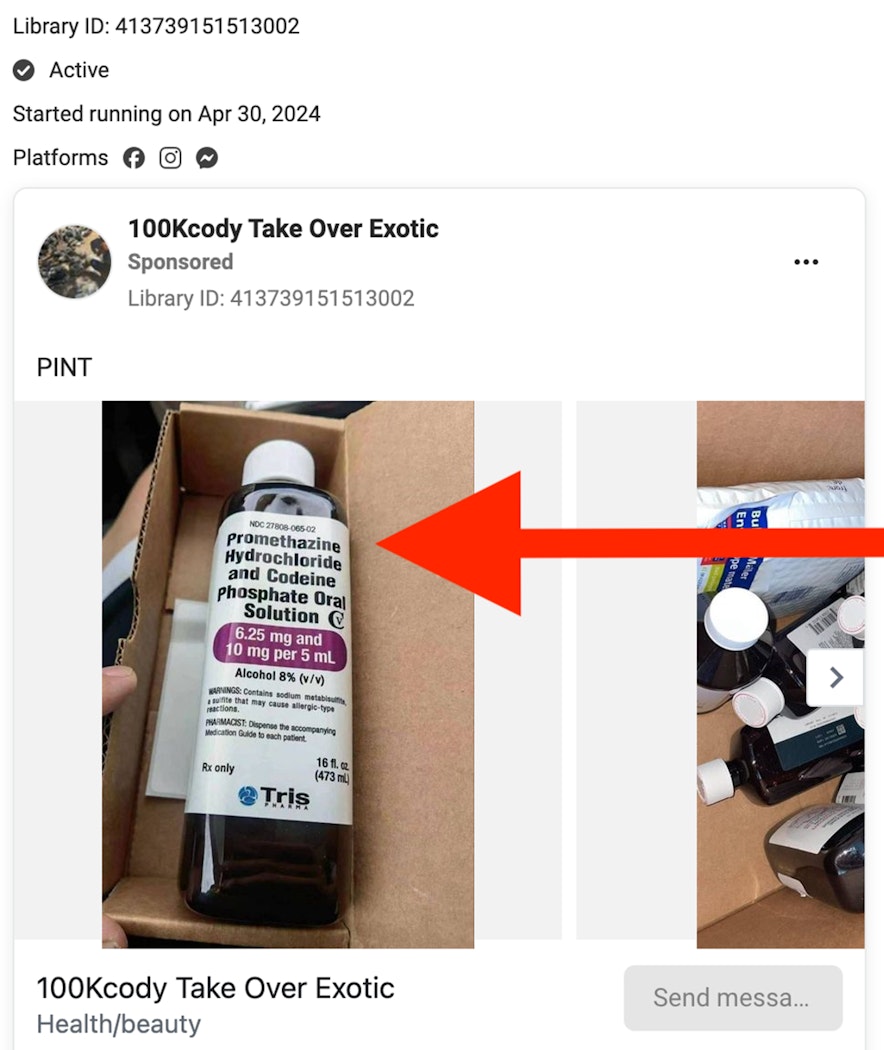

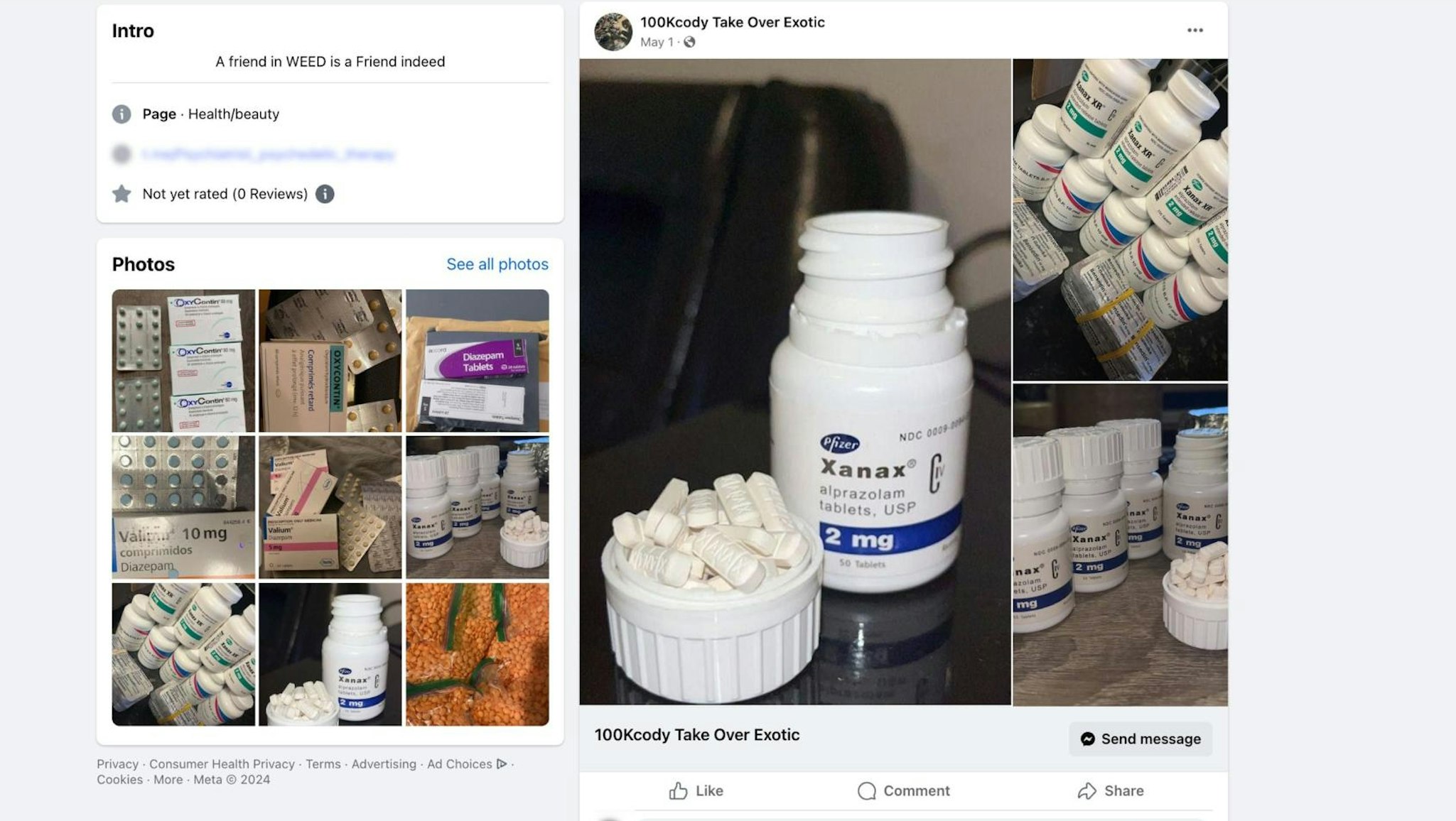

Many of the ads identified by TTP offered drugs on multiple Meta platforms. For example, one account ran ads on Facebook, Instagram, and Messenger on May 20, 2024, showing packages of OxyContin and piles of unidentified, brightly colored pills. The same account ran an ad the previous month for prescription cough syrup containing promethazine and codeine, which is used to make the homebrew mixture “lean.” OxyContin (a brand name for oxycodone) and codeine are opioids, a highly addictive class of drugs that is driving the drug overdose crisis the U.S.

The advertiser in this case was a Facebook page called “100Kcody Take Over Exotic,” which states, “A friend in WEED is a Friend Indeed.” Categorized as a "health/beauty" page, it is filled with photos and videos of drugs, including packages of Valium and bottles of Xanax. It also links to a Telegram account that gives prices for drugs and takes orders.

Meta approved these ads despite their apparent violation of the company’s policies. Facebook's Community Standards prohibit attempts to sell "high-risk drugs" and other "non-medical drugs" that are "used to achieve a high." The policy also bars attempts to sell prescription drugs, with limited exceptions for educational purposes or delivery offers from "legitimate healthcare e-commerce businesses." Instagram's Community Guidelines prohibit "buying or selling non-medical or pharmaceutical drugs."

Meta's advertising standards also bar ads that "promote the sale or use of illicit or recreational drugs, or other unsafe substances, products or supplements," as well as attempts to sell prescription drugs. The company says ads must adhere to both its advertising policies and each platform’s policies.

An ad that ran on Facebook, Instagram, and Messenger showed a carousel of drug images including packages of OxyContin.

An ad that ran on Facebook, Instagram, and Messenger showed a carousel of drug images including packages of OxyContin.

Another ad identified by TTP, which ran on Facebook and Messenger April 21-23, 2024, featured a video that panned over a pile of crystals with a note that read “MDMA” and mounds of orange and green tablets with a note that read “XTC,” short for ecstasy. (MDMA and ecstasy refer to the same party drug.) Clicking on the ad took users to Facebook page called “Carole kessler,” which showed photos of various pills, gummies, powders, and what appear to be magic mushrooms, and linked to a Telegram account called “PSYCHEDELICS TRIPPY FUN👽🌈.” The Meta Ad Library indicates the account was disabled for not following advertising standards, but it was able to run another ad in early June 2024.

Some advertisers even used the name of a drug in their name. For example, a Facebook page called “Ecstasy Meds” ran ad for pills on Facebook and Instagram starting on May 7, 2024. The account ran two other ads with the same content, the Ad Library shows.

One video ad that ran on Facebook and Messenger panned over a pile of crystals with a note that read “MDMA” and mounds of orange and green tablets with a note that read “XTC,” short for ecstasy.

One video ad that ran on Facebook and Messenger panned over a pile of crystals with a note that read “MDMA” and mounds of orange and green tablets with a note that read “XTC,” short for ecstasy.

The presence of these ads on Meta platforms raises questions about statements by Meta executives about how the company is doing its utmost to keep users safe.

At a Senate hearing on January 31, 2024, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg apologized to a group of parents whose children were harmed by social media, including some that died of drug overdoses, saying, “No one should go through the things that your families have suffered and this is why we invest so much.” He added that Meta is “going to continue doing industry-wide efforts to make sure no one has to go through the things your families have had to suffer.”

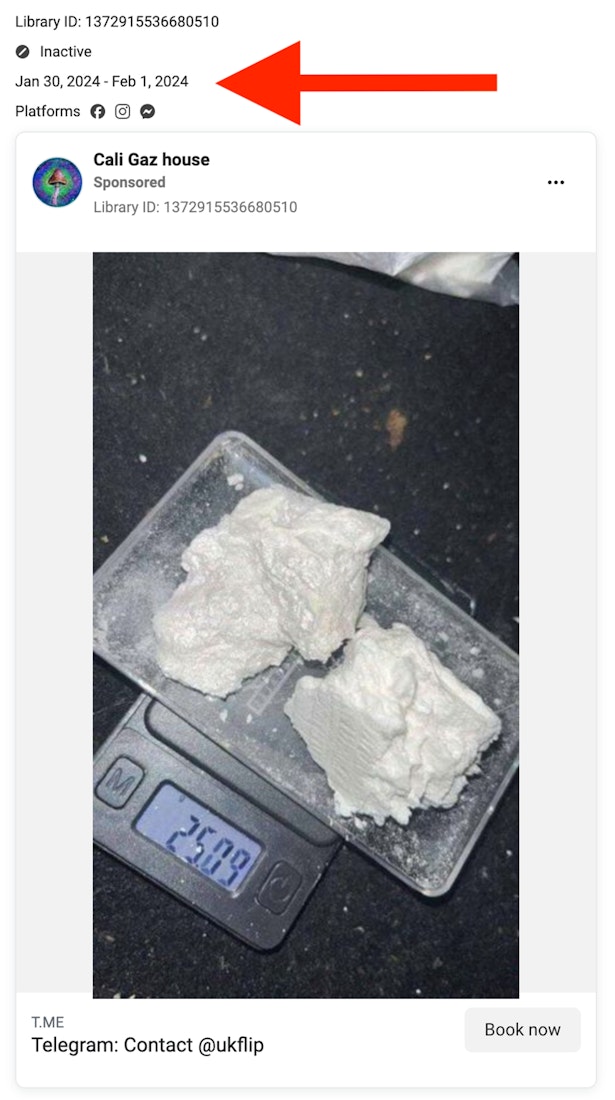

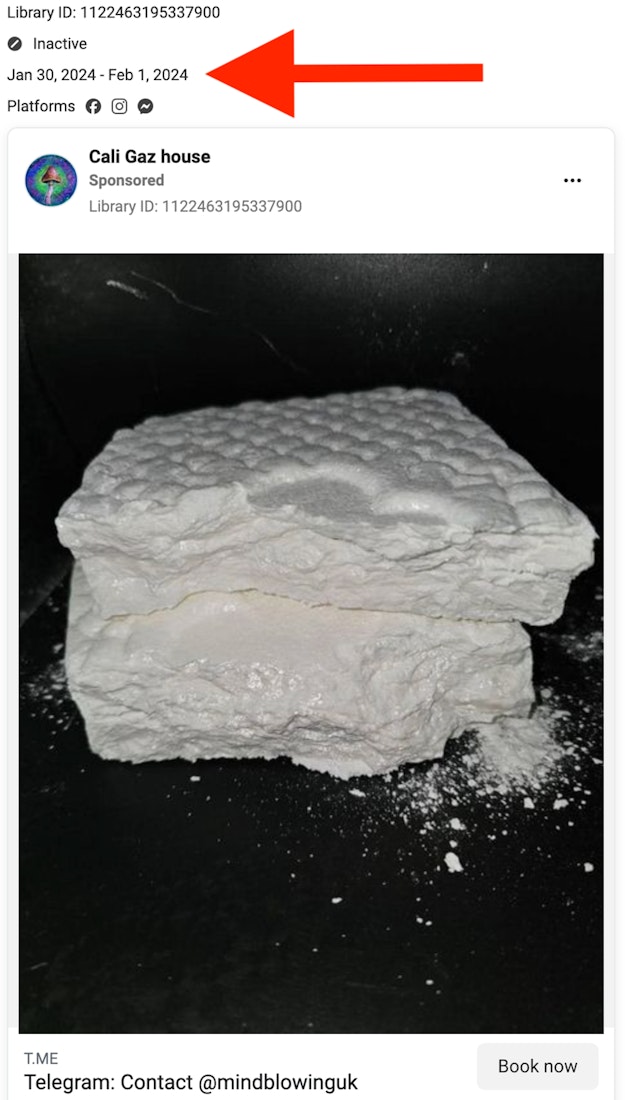

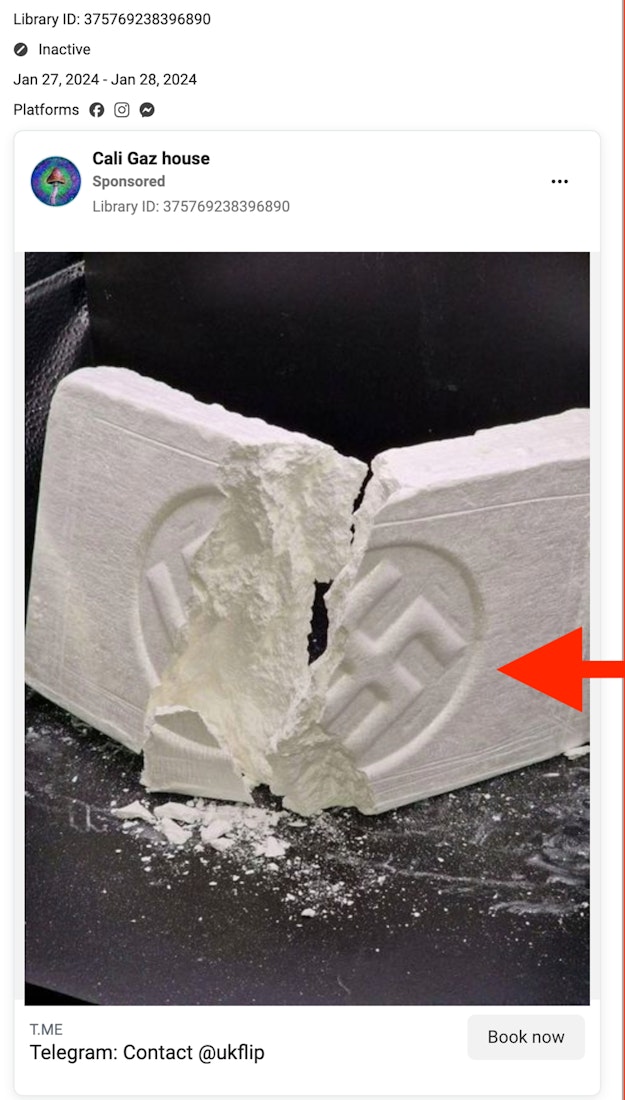

That same day, Meta ran two ads on Facebook, Instagram, and Messenger for chunks of a white powdery substance that appeared to be cocaine. The ads directed users to contact the dealer via Telegram accounts, including one called “Trippy house uk 🇬🇧 base 💊." The Facebook page behind the ads, “Cali Gaz House,” is filled with images of drugs and had a cover photo at one point that read, “Order Pay Receive.”

The page has run at least six similar ads, including one showing what looks like a cocaine brick stamped with a Nazi swastika symbol.

During a Senate hearing on Jan. 31, 2024, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg apologized to parents whose children were harmed by social media. Some of the families lost children to drug overdoses.

During a Senate hearing on Jan. 31, 2024, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg apologized to parents whose children were harmed by social media. Some of the families lost children to drug overdoses.

TTP examined several of the Telegram accounts linked in Meta drug dealer ads. One Instagram video ad from January-February 2024, which panned over bottles of codeine cough syrup, pointed to a Telegram account called “topcartstore.” Inside the Telegram account, the dealer gave the price of cough syrup, offered “high quality mdma” crystals for sale, and showed videos of U.S. Postal Service packaging—evidently to prove their ability to ship drugs to customers.

Another Facebook video ad that targeted users in Sweden in May-June 2024, showing packages of Oxycontin and Rivotril, linked to a Telegram account that told visitors, in Swedish, “Look, we sell all types of cannabis, hashish, psychedelic, cocaine, benzos, oxy, ketamine, diazepam at a good price. Buy medicine in Sweden 💊💊❄️🍫🍁.” Inside the Telegram account, the dealer showed images of multiple drugs and promised they could deliver all over Sweden and Norway.

The Facebook page that ran the ad is called “Sverigeplug,” which translates to “Sweden Plug”—“plug” being an apparent reference to a drug supplier. The drug Rivotril displayed in the ad is a brand name for clonazepam, a drug used to treat seizures and anxiety that is often abused by heroin and cocaine users.

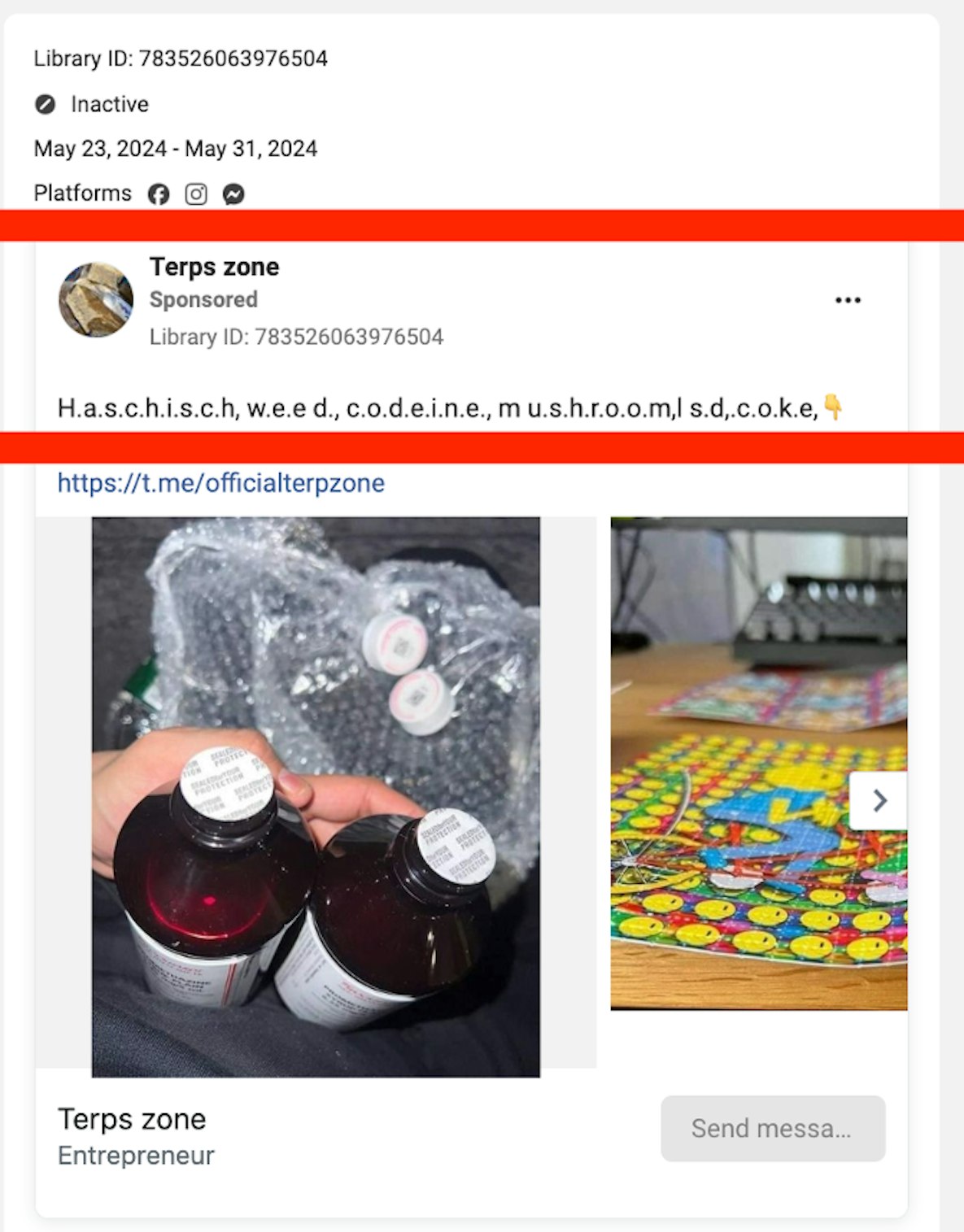

One ad that that ran on Facebook, Instagram, and Messenger in May 2024, with text spelling out drugs like “coke,” LSD, and mushrooms with a period in between each letter, linked to a Telegram account that gave prices for an array of controlled substances. One post in the Telegram account offered chunks of what appeared to be cocaine listed, in French, as “96% Colombian.”

An Instagram ad showing codeine cough syrup pointed to a Telegram account called “topcartstore.”

An Instagram ad showing codeine cough syrup pointed to a Telegram account called “topcartstore.”

EU and UK Drug Ads

The fact that Meta provides targeting and reach information for ads that run in the European Union gives a limited but useful window into how drug dealers use the ads to find customers. Of the 452 ads for drugs identified by TTP, 366 of them ran in the EU, collectively reaching more than 2,256,800 users in EU member countries and regions.

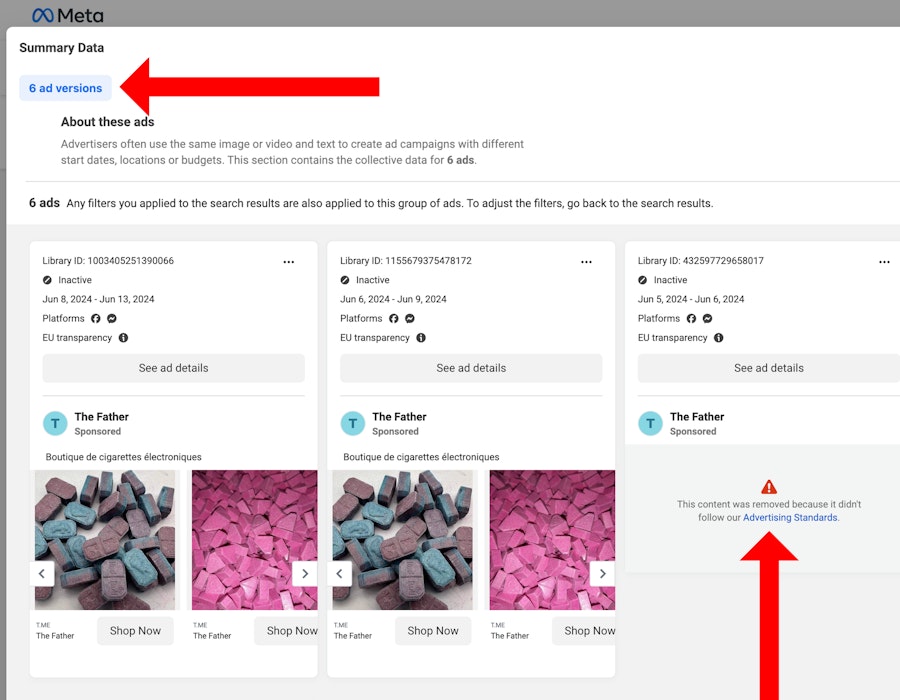

One set of six identical ads that ran on Facebook and Messenger in June 2024, showing a carousel of images of brightly colored pills and linking to a Telegram account, reached 192,831 users in 18 EU member states and regions, including France, Germany, and Italy, according to the Ad Library. The Library shows that Meta removed one of the ads for violating its advertising standards for Unsafe Substances but left the others alone. It was not clear why Meta took action on just one of the ads. The ads and the Facebook page behind them, called “The Father,” identify themselves as an electronic cigarette store.

Another ad that ran on Facebook, Instagram and Messenger in late May 2024, showing pills and what looks like a brick of cocaine, reached 40,344 users across 15 EU countries, including Greece, Poland, and Portugal. Like the example above, the ads and the Facebook page behind them identify themselves as an electronic cigarette shop.

One set of six identical pill ads that ran on Facebook and Messenger reached more than 192,000 users in 18 EU countries and regions. Meta removed one of the ads for violating its advertising standards but left the others alone.

One set of six identical pill ads that ran on Facebook and Messenger reached more than 192,000 users in 18 EU countries and regions. Meta removed one of the ads for violating its advertising standards but left the others alone.

TTP also identified a Facebook page called “One Stop Shop” that ran 50 ads showing the same photo of what appears to be a brick of cocaine stamped with the word “PRADA.” (Prada-branded cocaine is associated with the Mexico-based Sinaloa drug cartel, though it is not clear if the cartel was involved in this ad campaign.) According to Meta’s Ad Library, the ads, which ran in the UK and EU between March and June 2024, reached a collective 117,959 users in EU countries including Ireland, Austria, and the Czech Republic.

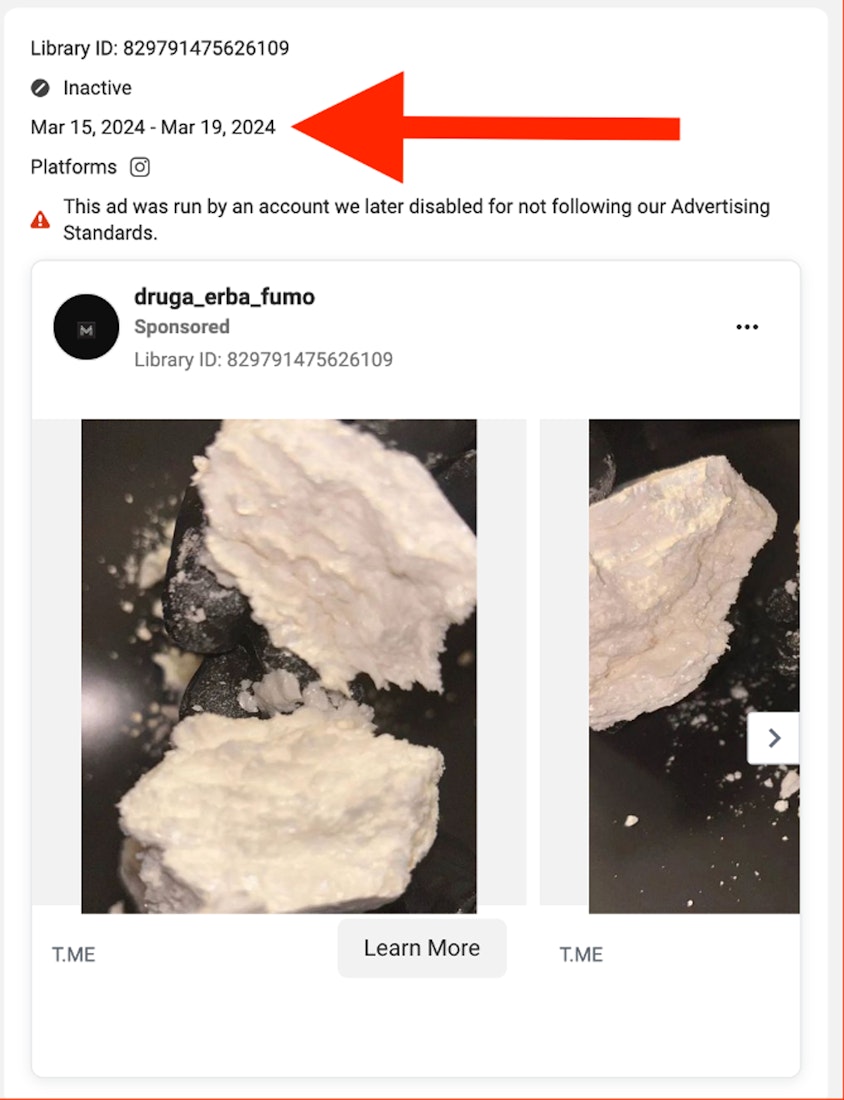

Meanwhile, an ad from the Instagram account @druga_erba_fumo, which showed what looks like cocaine, ran from March 15-19, 2024, in the EU. According to the Meta Ad Library, the ad reached more than 7,800 male users aged 23 to 56 in Italy. While the Ad Library shows a warning that the ad “was run by an account we later disabled for not following our Advertising Standards,” the Instagram account @druga_erba_fumo, which is filled with images of drugs and boasts that it offers the “best online shopping experience,” remains active. (“Erba fumo” translates to “smoke weed” in Italian.)

This ad from "One Stop Shop" shows what appears to be a brick of cocaine stamped with the word “PRADA.” Prada-branded cocaine has been linked to the Mexico-based Sinaloa drug cartel.

This ad from "One Stop Shop" shows what appears to be a brick of cocaine stamped with the word “PRADA.” Prada-branded cocaine has been linked to the Mexico-based Sinaloa drug cartel.

According to the European Union’s Digital Services Act (DSA), which came into force in 2022, “very large online platforms” defined as having more than 45 million users per month, are required to “act expeditiously to remove or to disable access” to illegal content upon “obtaining actual knowledge or awareness” of it. The European Commission designated Facebook and Instagram as "very large online platforms" in April 2023.

EU laws and the laws of member states define what is considered "illegal content." According to the European Union Drugs Agency, all countries in the EU have penalties for supplying drugs, including production, trafficking, selling, and possession with intent to distribute.

Online ‘pharmacies’

Meta says it reviews ads before they appear on Facebook or Instagram to ensure they meet its advertising standards. According to Meta, this review system “relies primarily on automated technology” and may take into account an ad’s images, video, text, targeting information, and where it directs users who click on the ad. The company says its enforcement “isn’t perfect” but describes its efforts in this area as one of continual improvement and “testing and implementing new approaches.”

But TTP found that Meta often approved ads that were very clear about their drug dealing agenda in both their text and images. Many of these ads were from accounts posing as pharmacies.

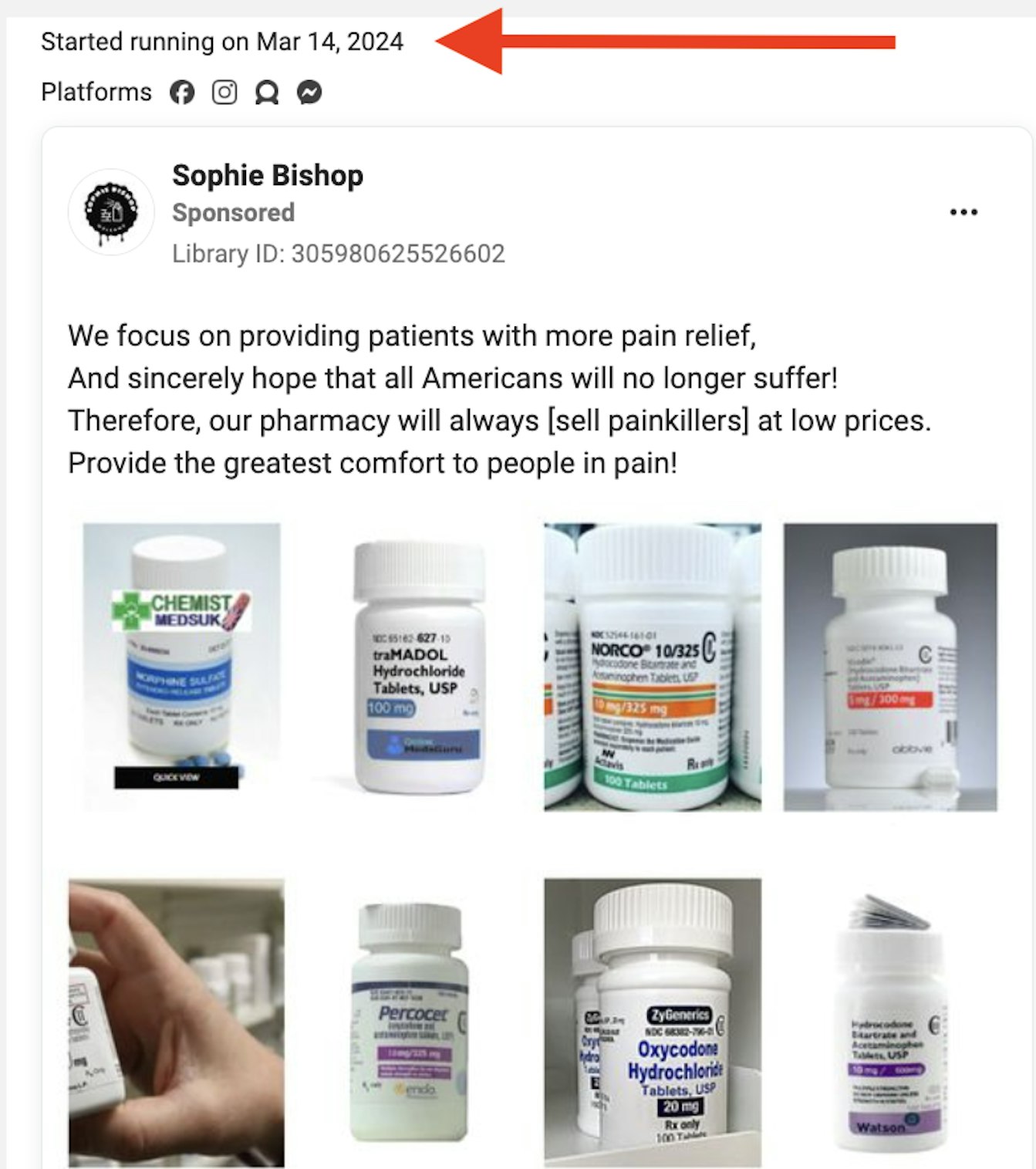

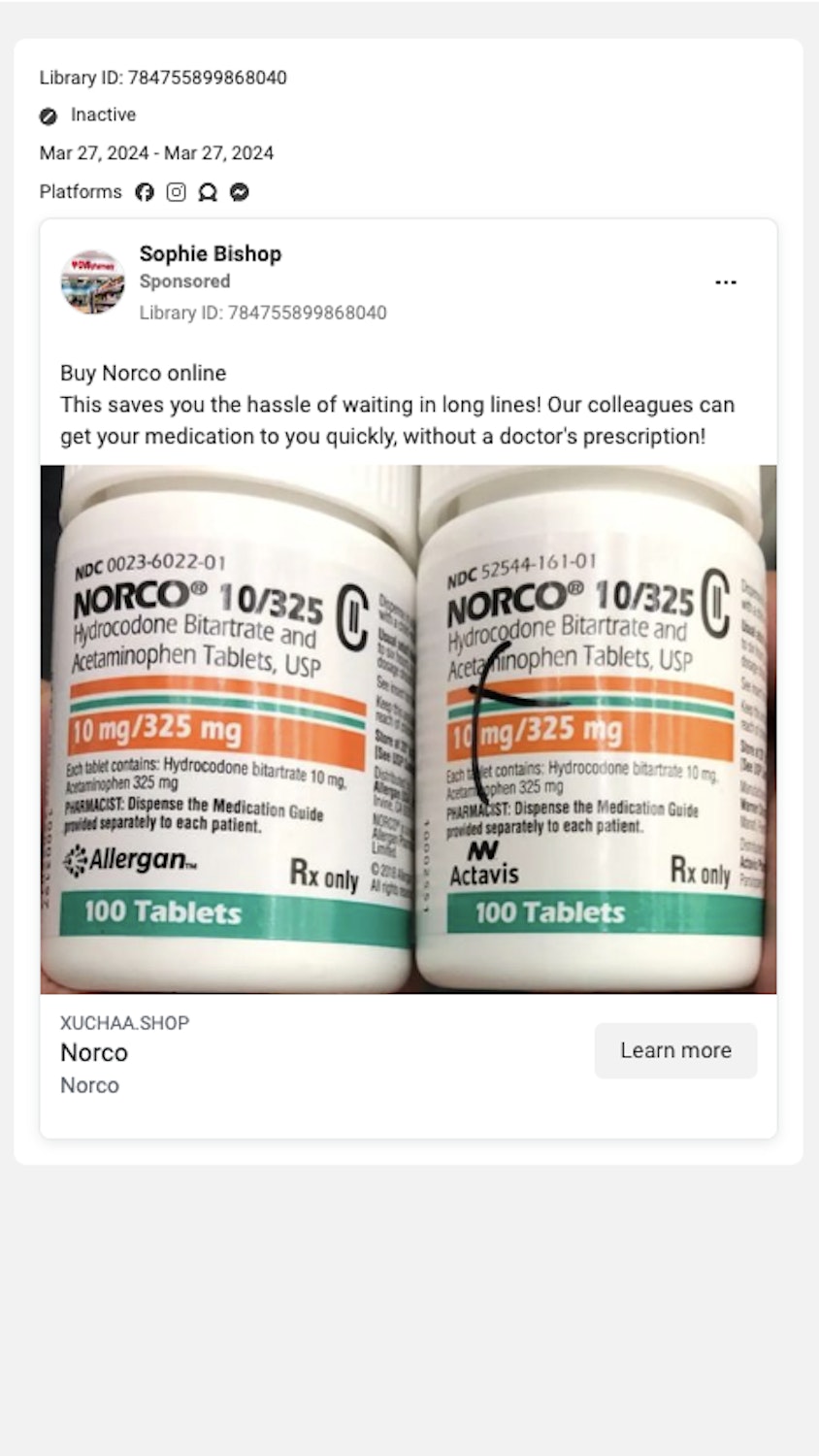

One ad that ran on March 27, 2024, showed bottles of the prescription drug Norco, a painkiller that combines the opioid hydrocodone and acetaminophen. The text read, “Buy Norco online. This saves you the hassle of waiting in long lines! Our colleagues can get your medication to you quickly, without a doctor's prescription!” The ad ran on Facebook, Instagram, Messenger and Meta’s Audience Network of mobile apps. The Facebook page behind the Norco ad, which uses the name “Sophie Bishop,” has a cover photo and profile image of a CVS pharmacy store and gives its location as Huzhou, China. The page posted a collage of photos including a smiling pharmacist and bottles of prescription drugs including morphine, oxycodone, and the synthetic opioid fentanyl. The ad linked to an online store that has since been deactivated.

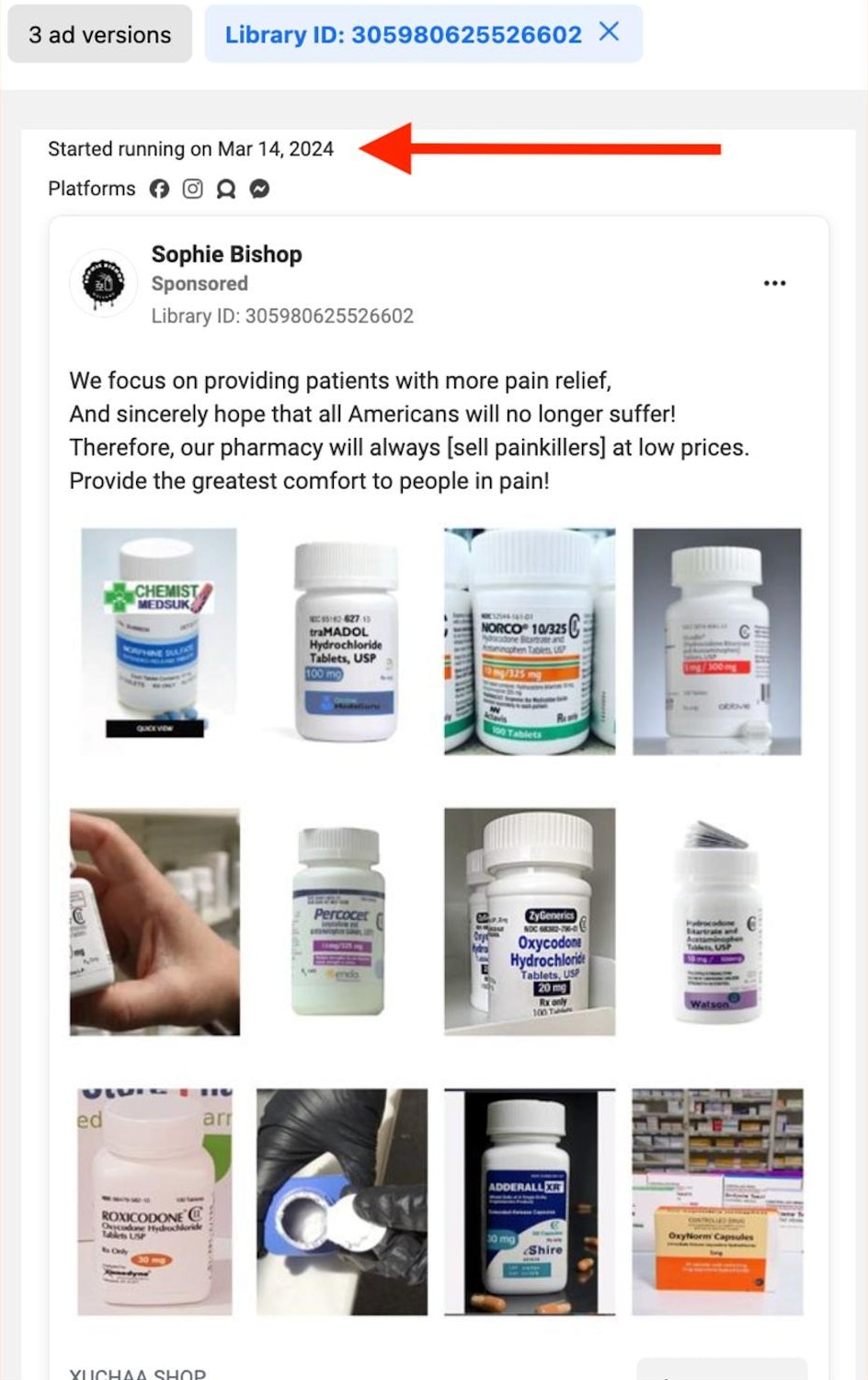

The same Sophie Bishop page ran an ad starting March 14 that showed an array of prescription drugs including Norco, tramadol, oxycodone under various brand names, and Percocet, which combines oxycodone and acetaminophen. The ad, which pointed to the same online store as the previous ad, stated, “We focus on providing patients with more pain relief” and “sincerely hope that all Americans will no longer suffer!” Touting its pharmacy’s low prices, it ended with, “Provide the greatest comfort to people in pain!” The ad ran on Facebook, Instagram, Messenger, and Meta’s Audience Network.

TTP identified another ad offering “Xanax leaked from a hospital” that ran in late March 2024 on all four Meta platforms and used the same text as the previous Sophie Bishop ad described above. The Facebook page that ran the ad, called “Irene Miles,” looks identical to the Sophie Bishop page, with the same CVS cover and profile photos and the same post showing a pharmacist and prescription drugs. Both the Irene Miles and Sophie Bishop pages are categorized as “electronics.”

This ad offered to sell Norco, a drug that combines the opioid hydrocodone and acetaminophen, without a prescription.

This ad offered to sell Norco, a drug that combines the opioid hydrocodone and acetaminophen, without a prescription.

The Facebook “pharmacy” pages behind these ads appear to violate Meta’s policies against selling prescription drugs and may also violate Facebook’s Community Standards on inauthentic behavior. That policy prohibits people from misrepresenting themselves, using fake accounts, or engaging in behaviors “designed to enable other violations under our Community Standards.” Facebook further prohibits “coordinated inauthentic behavior” between multiple assets.

This “pharmacy” activity on Meta may also violate U.S. law. According to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act prohibits offering prescription drugs for sale without a prescription. The agency has repeatedly warned about illegal online pharmacies that sell dangerous and potentially deadly counterfeit drugs, using legitimate-looking websites.

Meta’s fellow tech giant, Google, got ensnared in a U.S. government investigation of rogue online pharmacies more than a decade ago. In 2011, Google paid $500 million to avoid Justice Department prosecution for running ads for Canadian pharmacies illegally selling prescription drugs to American consumers.

Threat of a lethal dose

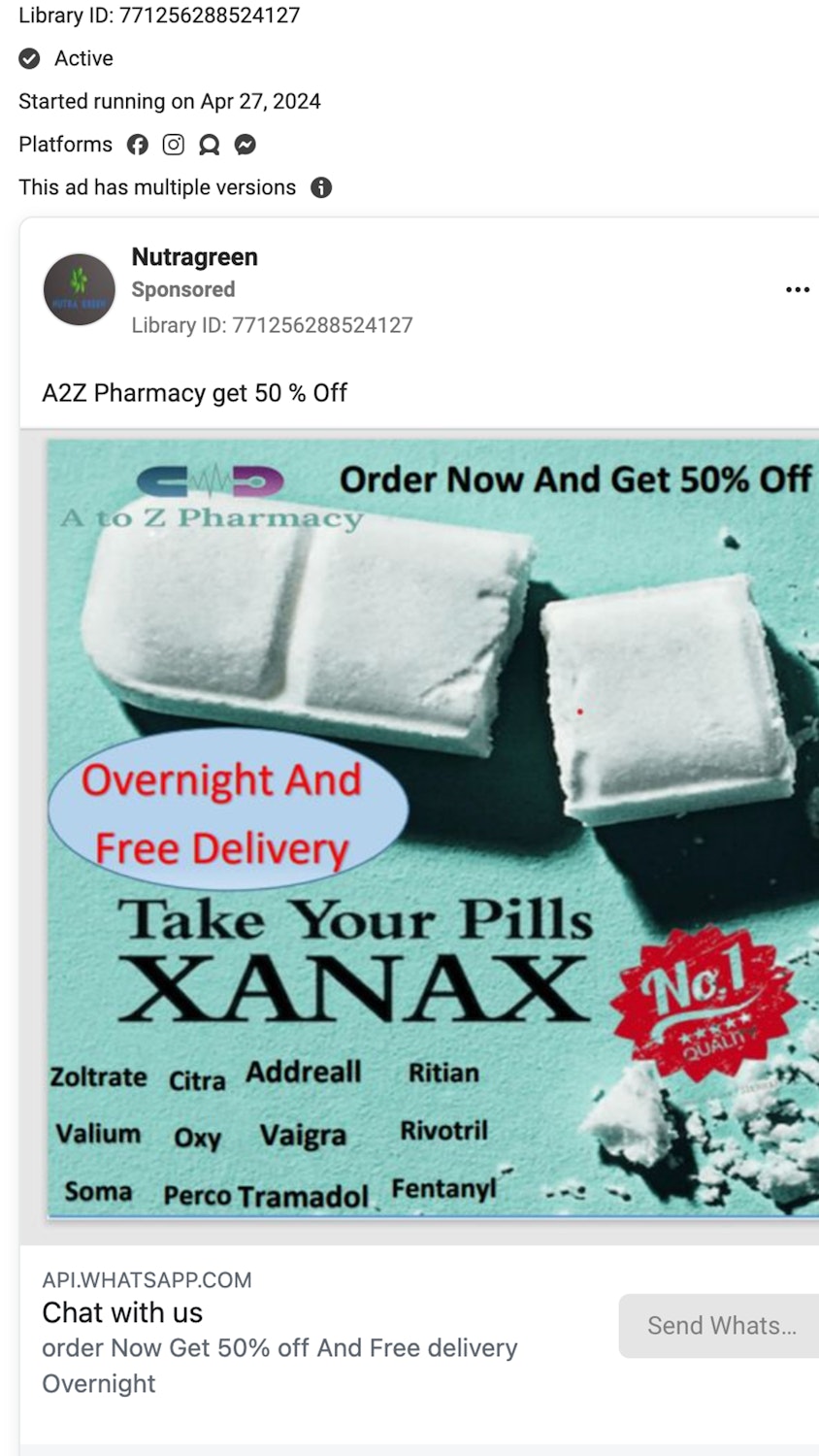

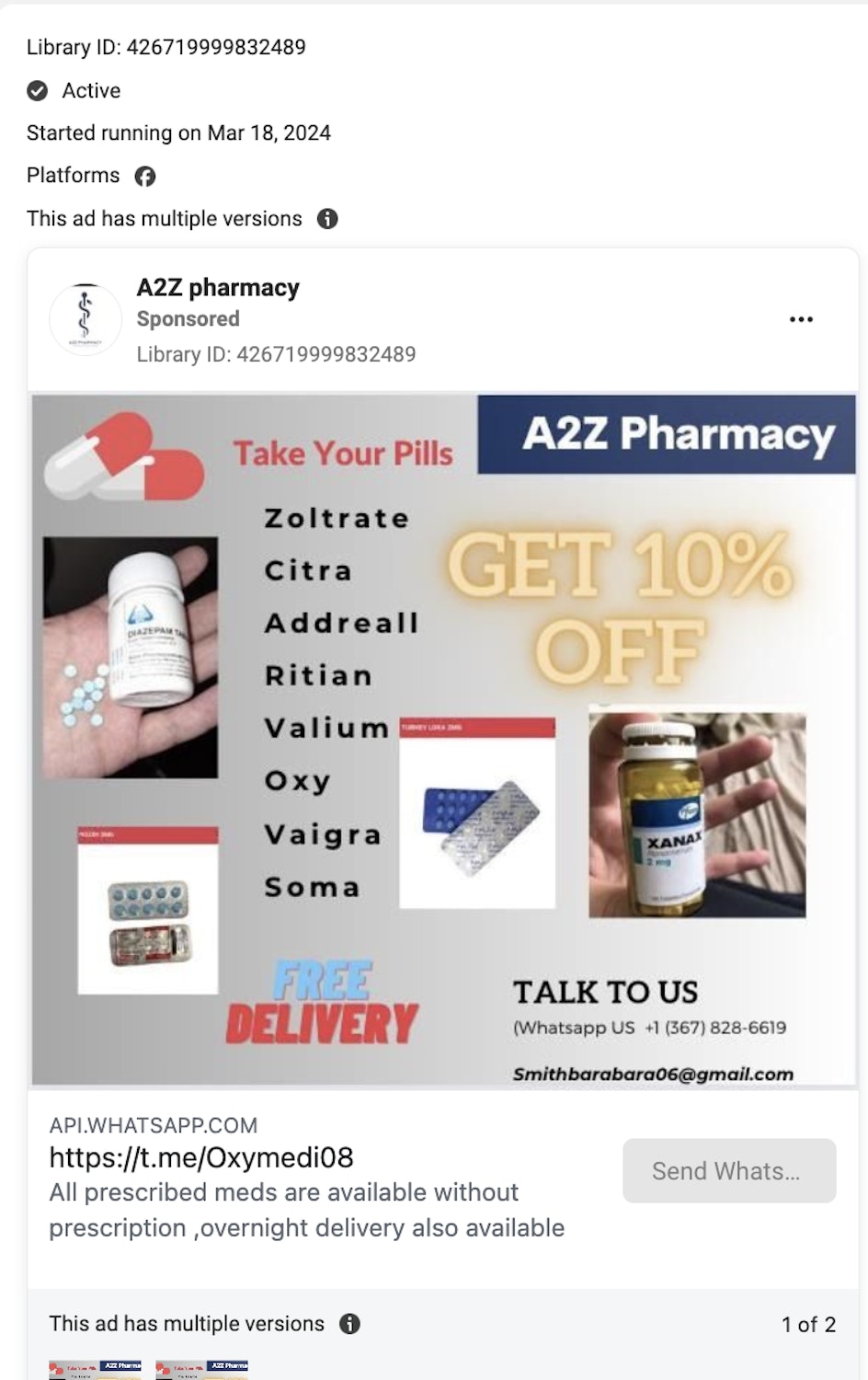

One ad identified by TTP promoted something called “A2Z Pharmacy.” The ad, which ran on Facebook, Instagram, Messenger, and Meta’s Audience Network starting on April 27, 2024, showed a white tablet with the text, “Take Your Pills,” and a list of drugs including Xanax, Valium, Percocet, OxyContin, tramadol, Adderall, and fentanyl. The ad, from a Facebook page called “Nutragreen,” promised “Overnight and Free Delivery” and “Order Now And Get 50% Off.” It connected to a WhatsApp number.

A Facebook page going by the name “A2Z Pharmacy” ran an ad in March 2024 with the same catchphrase “Take Your Pills” and a list of many of the same drugs. It linked to a Telegram account called @Oxymedi08 that offers “Meds Bulk & dropship.” The Facebook page, categorized as “medical & health,” had a profile photo of a snake entwined around a staff, a symbol of medicine that is used by the American Medical Association. The page’s cover photo touted A2Z Pharmacy as “Your Trusted Source for Health,” and the page had multiple posts of pill packets including “Oxy,” Xanax, and Rivotril.

This "A2Z Pharmacy" ad promised overnight and free delivery for drugs including Xanax, Valium, Percocet, and OxyContin.

This "A2Z Pharmacy" ad promised overnight and free delivery for drugs including Xanax, Valium, Percocet, and OxyContin.

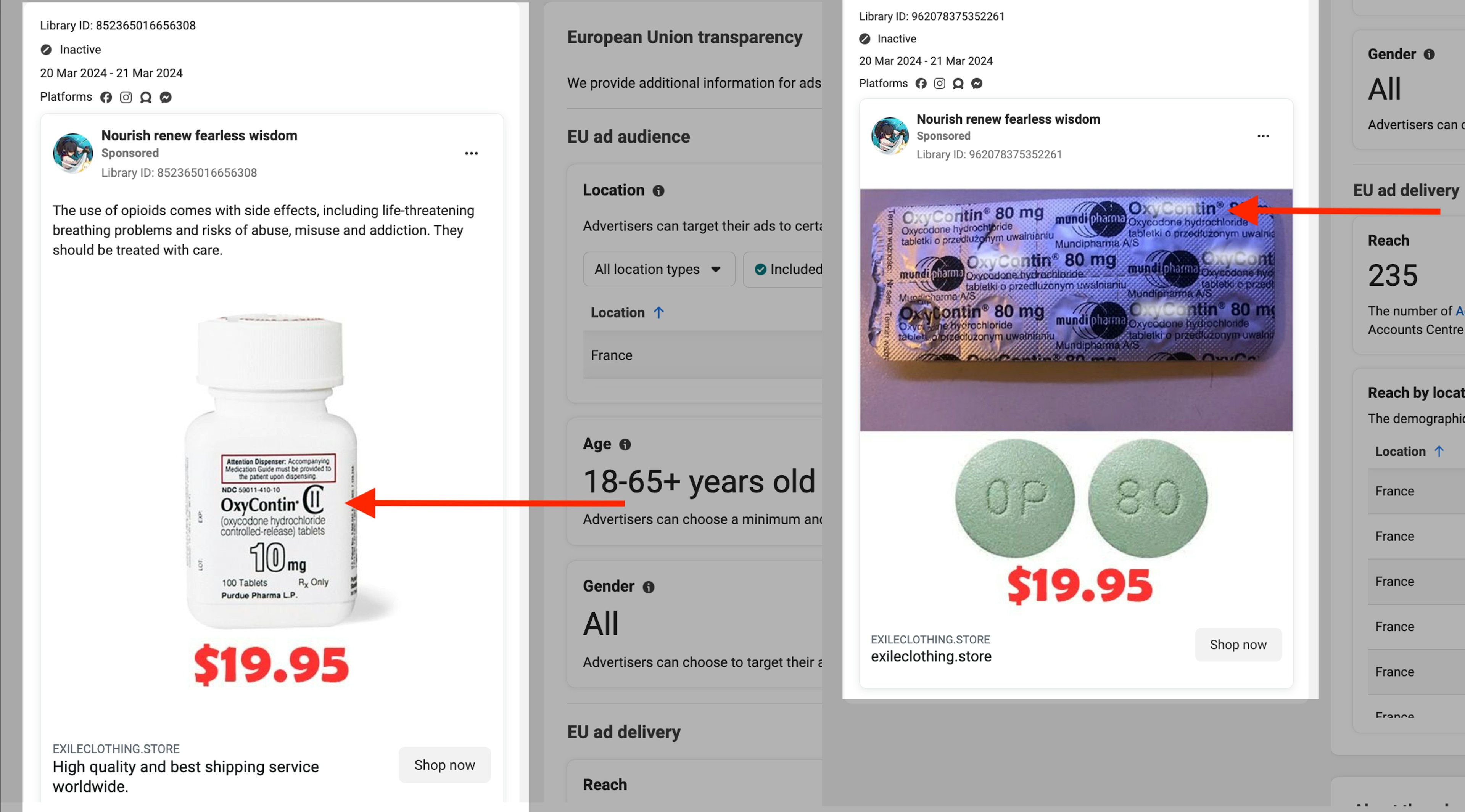

Another ad that ran on all four Meta platforms March 24-25, 2024, showed a prescription pill bottle and pills superimposed over a photo of a Purdue Pharma corporate building. (Purdue Pharma is the maker of OxyContin.) The text read, “Who doesn’t like to save money? Take advantage of this end-of-season sale where you can choose from a variety of products with discounts of up to 70% off.” The ad linked to an online store.

The Facebook page behind the ad, “Nourish renew fearless wisdom,” identifies itself as a social media agency based in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. TTP identified at least two other ads from this page that offered OxyContin pills.

This ad showed a corporate sign from Purdue Pharma, the maker of OxyContin, and promised discounts on pills.

This ad showed a corporate sign from Purdue Pharma, the maker of OxyContin, and promised discounts on pills.

Fake online “pharmacies” may be selling more than just legitimate drugs. As documented by multiple media reports in recent years, teenagers often unwittingly buy counterfeit pills laced with fentanyl via social media, with deadly results. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration says seven out of 10 pills seized by its agents contain a lethal dose of fentanyl. Many of the fake pills are made to look like the prescription drugs OxyContin, Percocet, Vicodin, Xanax, and Adderall, according to the agency.

It is not clear why Meta’s automated systems, which consider an ad’s text and images, failed to register the obvious signs of drug dealing in the ads highlighted in this report. Meta has talked up the ability of its automated systems to understand text in images, which would presumably include prescription drug labels.

Instagram update

TTP also revisited the results of its earlier investigation of drug dealing from December 2021. That investigation found that Instagram allowed teen users as young as 13 to find potentially deadly drugs for sale in just two clicks.

At the time, TTP reported 50 Instagram posts to Meta that appeared to violate the company’s policy against selling drugs on its platforms, and Instagram responded that 72% of the flagged posts (36) did not violate its Community Guidelines, despite clear signs of drug dealing activity.

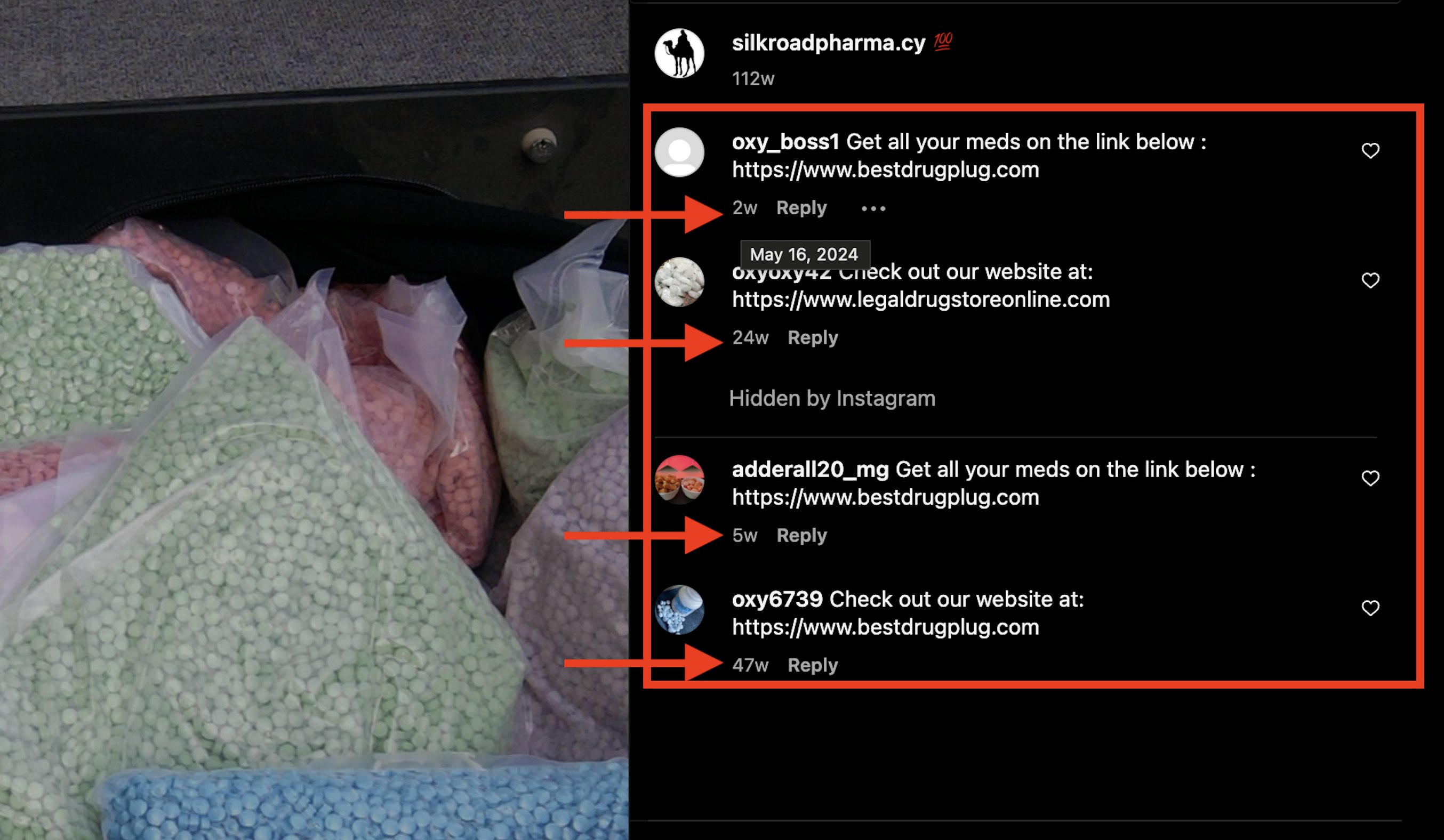

As of June 2024, TTP found that seven of the 50 accounts behind those drug dealing posts remain present on Instagram. One of the remaining accounts, with the handle @silkroadpharma.cy, has been inactive since 2022, but its old posts continue to draw other drug dealers looking for buyers. (The account’s name refers to the notorious dark web marketplace known as the Silk Road.)

One @silkroadpharma.cy post from April 10, 2022, which shows plastic bags filled with colorful pills, got a comment on May 16, 2024, from an account called @oxy_boss1, which encouraged users to visit a website called “Best Drug Plug.” The site sells drugs including opioids, ketamine, ecstasy, cocaine, heroin, LSD, and fentanyl.

An Instagram account called @adderall20_mg commented on the same post on April 24, 2024, telling users to “Get all your meds” at the same website noted above. These comments show how Meta’s failure to act on drug dealing accounts brought to its attention can continue to cause harm for years afterward.

An Instagram drug dealer account that TTP identified in 2021 is no longer active, but its old posts continue to draw other drug dealers looking for buyers.

An Instagram drug dealer account that TTP identified in 2021 is no longer active, but its old posts continue to draw other drug dealers looking for buyers.

Conclusion

TTP’s investigation highlights another facet of Meta’s drug problem: advertising.

By running hundreds of ads that offer prescription and recreational drugs, the company is allowing content that not only appears to violate its own policies but also, in some cases, U.S. law. What’s more, Meta is financially benefitting from these drug dealer ads, which pose potential dangers to its users.

TTP’s findings show that Meta repeatedly missed or ignored obvious signs of drug dealing activity in ads, raising questions about its automated review process and statements by company executives about their commitment to user safety.

Recent reporting suggests Meta’s Instagram is testing “unskippable” ads, something that would presumably increase the company’s advertising revenue. Until Meta devotes similar energy to improving enforcement of its own drug policies, the problem of drug dealing on the platform is likely to persist.